Biggest solar flare of the year showers the Earth

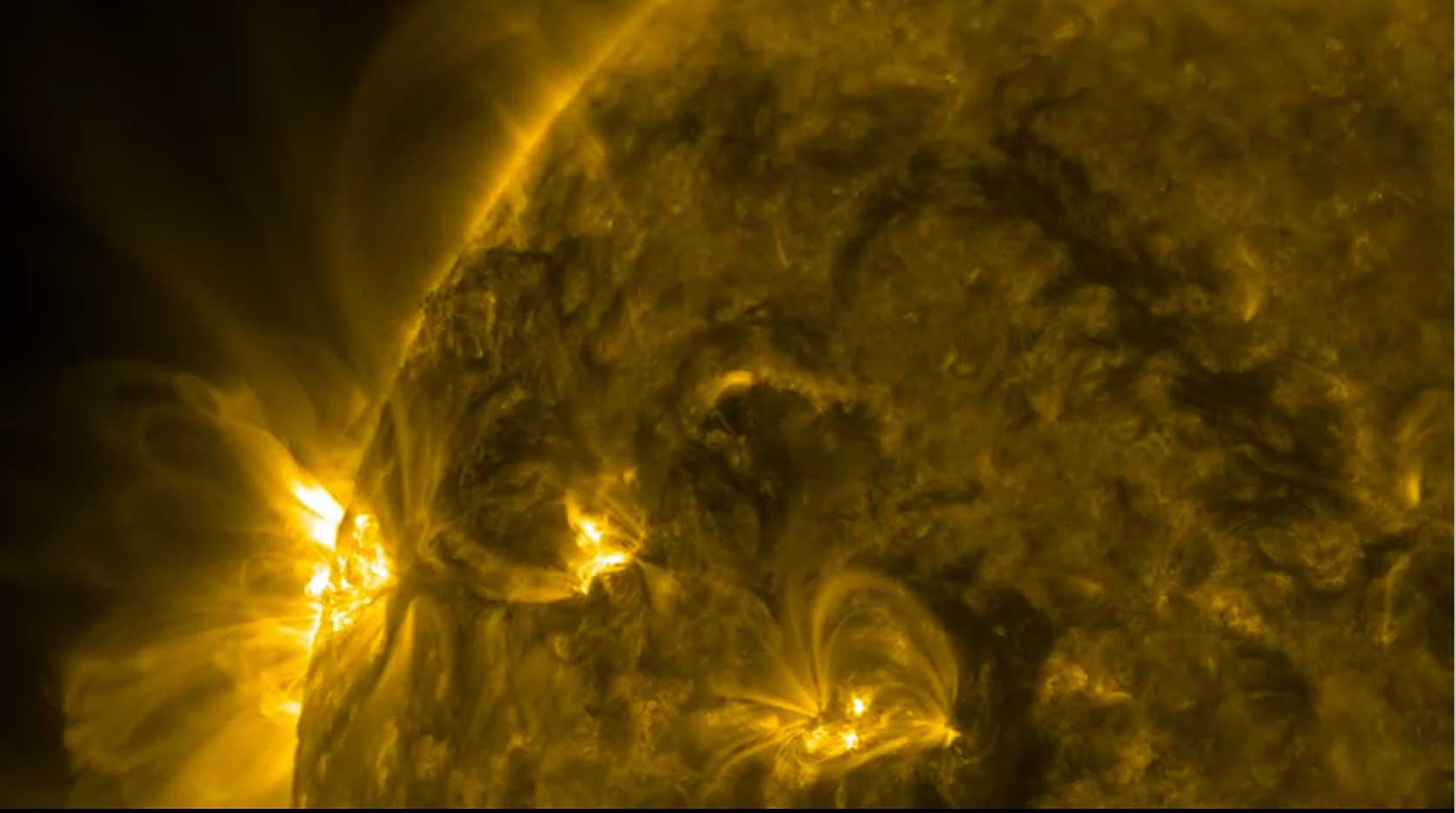

Earlier this month, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory spotted a massive solar flare, rated at class X2.7, erupting from the surface of the sun. Orbiting observatories have also been keeping an eye on a group of sunspots on the solar surface. This flare, which peaked at 6:11 pm EDT on May 5, 2015, is classified as an X2.7-class flare. X-class are the most intense flares, while the number provides indication about its strength.

"Weather" in space is a complicated idea. Yet it has a real impact on life on Earth. Basically, it's the stuff that is spewed out by the Sun and other stars — electromagnetic energy and solar material — that travels through our solar system and interacts with everything it comes across, including the Earth's magnetic field.

Space weather is monitored by NASA and other agencies to alert us when solar activity that starts 92 million miles away might affect life on the ground. Now, a group of spots on the sun’s surface are drawing the attention of scientists.

On May 5, a sun spot started to rotate into view on the edge of the Sun's surface and then erupted with a bright explosion, spewing huge amounts of X-rays, ultraviolet light, solar material and particles. The flare was spotted by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. Solar flares are rated on a scale similar to how earthquakes are rated, and the biggest ones are known as "X-class flares." The one that hit Earth recently is classified at X2.7, the largest one reported this year.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D2ADlxet9460%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

"This was a solar flare and it also had this associated thing called a coronal mass ejection,” says Alex Young, associate director for science in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. "It was a relatively big one and so it’s pretty bright and spectacular, and it always gets our attention when it does that."

Predicting solar weather is difficult, Young says. Sun spots are complex systems and scientists have to make predictions based on past observations. The Earth's magnetic field protects us from most solar radiation, acting like a bubble that quivers when blasted by solar wind. Still, when the solar wind is intense enough, it can create the aurora borealis, GPS interference, disruptions to aviation and satellite communications, and power grid fluctuations. It can even take the power grid down in a worst-case scenario, and power companies are prepared to take action if that happens.

"All we can do is look back in history and say every time we’ve seen a sunspot like that before, we know that it gives off so many of these types of flares. And we can just come up with a percentage," he says. "It’s unfortunately not the kind of accuracy that we would like."

One of the most difficult things scientists want to understand is the interaction of the plasma and magnetic fields inside the sun.

"We do see things moving around, we see these massive rivers of solar plasma. … And there’s also this stuff that flows to the surface, this magnetic field," Young says. It happens throughout the entire universe, Young says, so it’s critical to understand.

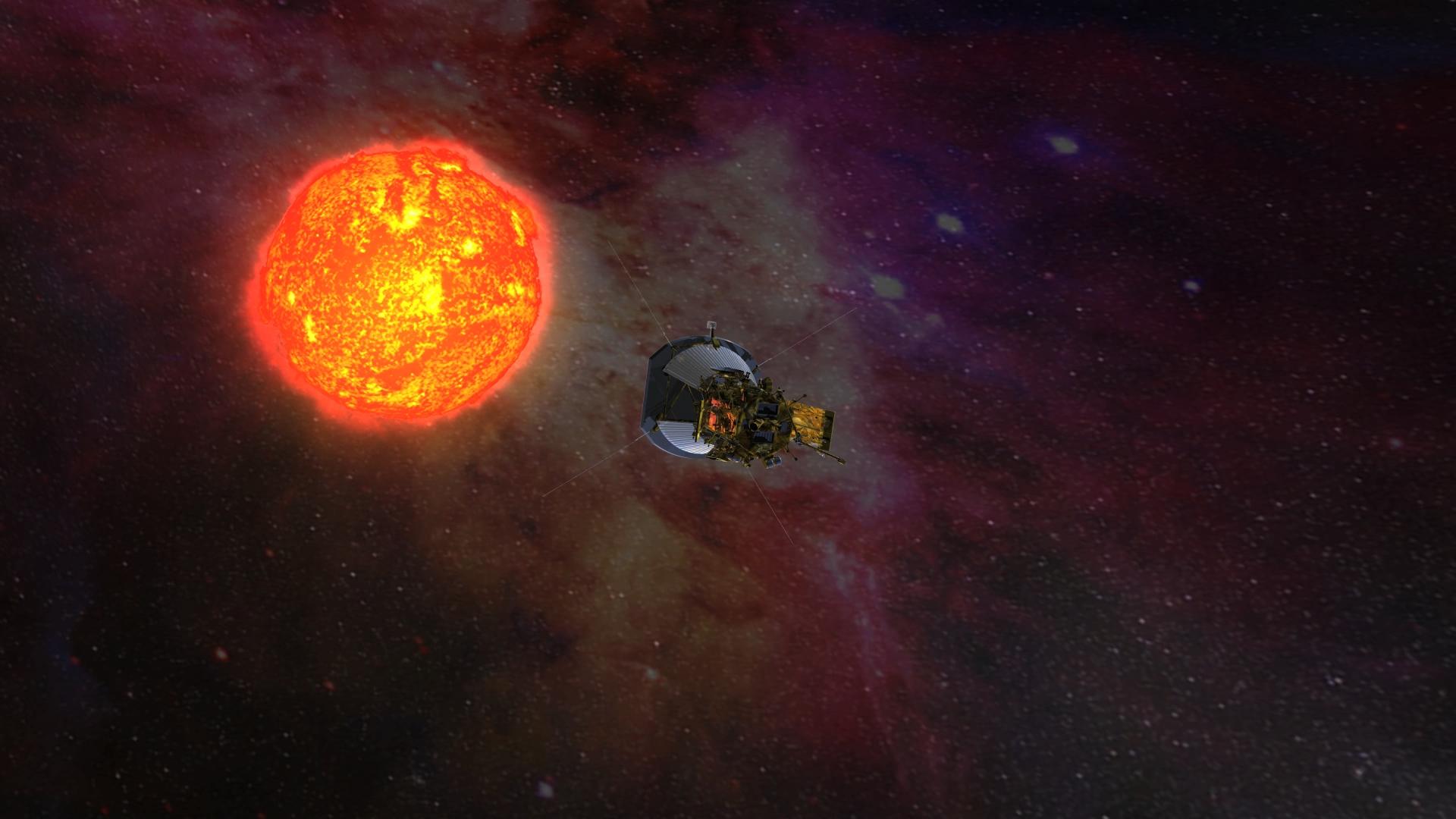

In the future, scientists hope the Solar Probe Plus will give them the sort of data that will allow them to make better informed forecasts about solar activity. The probe is expected to launch July 30, 2018 and will reach its closest approach to the sun six-and-a-half years later. The probe will orbit the sun, spiraling closer until it gets to be about 4 million miles away, just dropping into the solar atmosphere. With each orbit, the probe will take samples of the solar atmosphere, shoot and transmit imagery and measure solar particles.

"It’s going to be an amazing mission because it’s got some huge technological challenges, things like special shielding to handle the really harsh environment," Young says. "We’re going to fly through and just kind of run our hands through the outer atmosphere of the sun," Young says.

This story is based on an interview from PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.