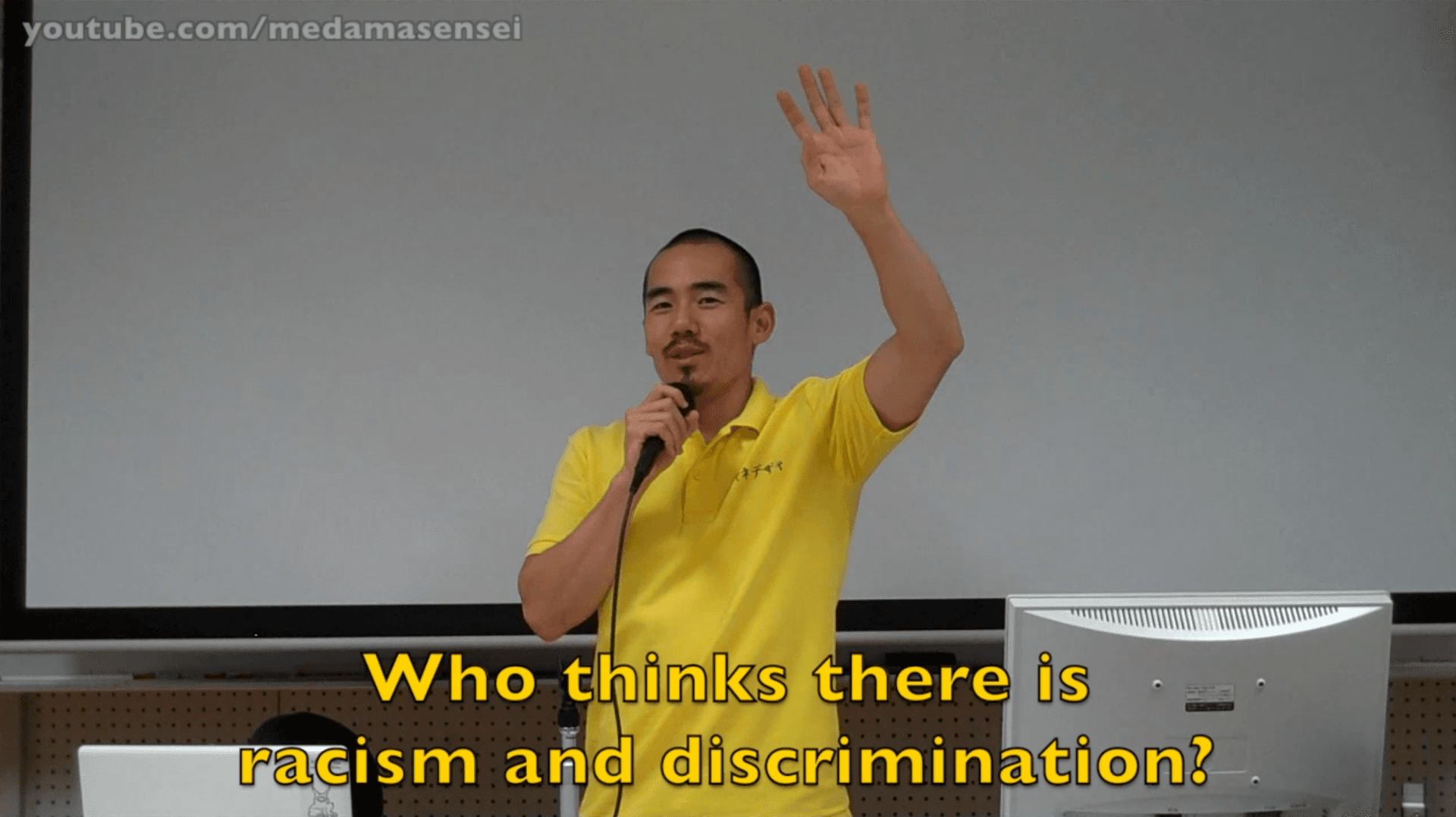

A screen shot from Miki Dezaki's YouTube video about racism in Japan.

Growing up in southern Florida, Miki Dezaki was exposed to a lot of stereotypes. The kids around him made jokes about people from Asia — and his immigrant Japanese parents said derogatory things about other Asians.

He was so sensitive to stereotypes from such a young age that he "would purposely get bad grades because I didn’t want to be the smart Asian in middle school," Dezaki remembers.

But after he graduated from college and went to teach English in Japan, he realized that the situation might actually be worse in Japan. There, no one talks about it. There’s a generally accepted mythology in Japan that the country is homogenous. And if the country is homogenous, then racism and discrimination don’t exist.

But Dezaki knew better. He taught at a high school in Okinawa, the Hawaii of Japan. Okinawans are actually a separate ethnic group, known as Ryukyuan, and they’re just one of many minorities in Japan who have long faced discrimination. Many Okinawans have painful memories of abuse by Japanese soldiers during World War II. It’s still not uncommon in Tokyo today for a landlord to refuse to rent to someone who’s Okinawan — or Chinese. Or Korean. Or white.

“I don’t think anything has changed, and there’s no dialogue about it," Dezaki says. Despite Okinawa's history, Dezaki’s students viewed racism as an American problem, something they’d seen on TV. Even his coworkers, "the teachers, educated people, really knew nothing about it either."

So when Dezaki's head English teacher told him that he could teach anything he wanted for his last lesson in Okinawa, he decided to do one on discrimination.

He started that class by asking his students if they thought there was such a thing as racism and discrimination in Japan. "In every class, only two or three students out of 40 raised their hands," he says. And the only kind of discrimination those students could think of was against handicapped people, because they’d had a special class on it.

In the lesson, Dezaki went on to describe different kinds of discrimination, ones based on race, sexuality, nationality or even just judging the kid next to you before giving him or her a chance. He spoke about how people form discriminatory ideas and how they can be changed.

Students loved it, teachers loved it and the vice principal asked him to teach the lesson to every class in the school.

Then Dezaki, who already had a popular channel on YouTube, put a version of the lesson online. The video starts with a disclaimer: “I just want to say that I know there’s a lot of racism in America. And I’m not saying that America is better than Japan or anything like that. I just want to get that out of the way.”

At the time, Dezaki was preparing to move to Southeast Asia to become a Buddhist monk, something he’d been planning for a long time. To say he wasn't prepared for what happened next would be a bit of an understatement.

“I was saying goodbye to a lot of life. You know, I was thinking this is maybe end of my life in society," he says. "And then I uploaded the video and I’m getting death threats, people freaking out on me."

Right-wing extremists online, known as the “net uyoku," pounced on Dezaki’s video, saying it was full of lies and Japan-bashing.

Along with death threats, they posted all of his personal information online and started calling his school. Pretty soon co-workers were pressuring him to take down the video, claiming that students would be hurt and that the JET Program, the one that brought him to Japan to teach English, would be stopped in Okinawa because of him.

Dezaki says he felt terrible for putting his school through it, but he also "started to feel a little angry that they wouldn’t support me. I was like, 'You guys are teachers, and you guys don’t support freedom of speech.'"

The video stayed up.

After a couple months, things mostly died down. But some of Dezaki’s former coworkers, friends of his, still don’t talk to him.

Dezaki left monkhood last year to help take care of a sick family member back in the US. He’s now planning to return to Japan to do research on how censorship and the government’s revision of history affect Japanese youth.

Eventually, he says, he wants to go to back to making videos — documentaries this time, ones that can help keep up the dialogue he first ignited.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!