A Guatemalan spring? Youth-driven protests demand resignation of leaders

A protester hits a pot during a demonstration to commemorate International Labour Day in downtown Guatemala City, May 1, 2015. International Workers' Day, also known as Labour Day or May Day, commemorates the struggle of workers in industrialised countries in the 19th century for better working conditions. The signs read, "You resign now!" (R) and "To jail for the thieves" (C), alluding to a political corruption scandal involving 20 senior officials who are accused of leading a massive network of customs fraud and tax evasion operating in the ports of the Central American country.

News that a massive government corruption scheme involving more than a dozen high-ranking officials had been uncovered in Guatemala last month seemed at the time like just another piece of bad news in a country that has seen more than its fair share of political dysfunction and crisis.

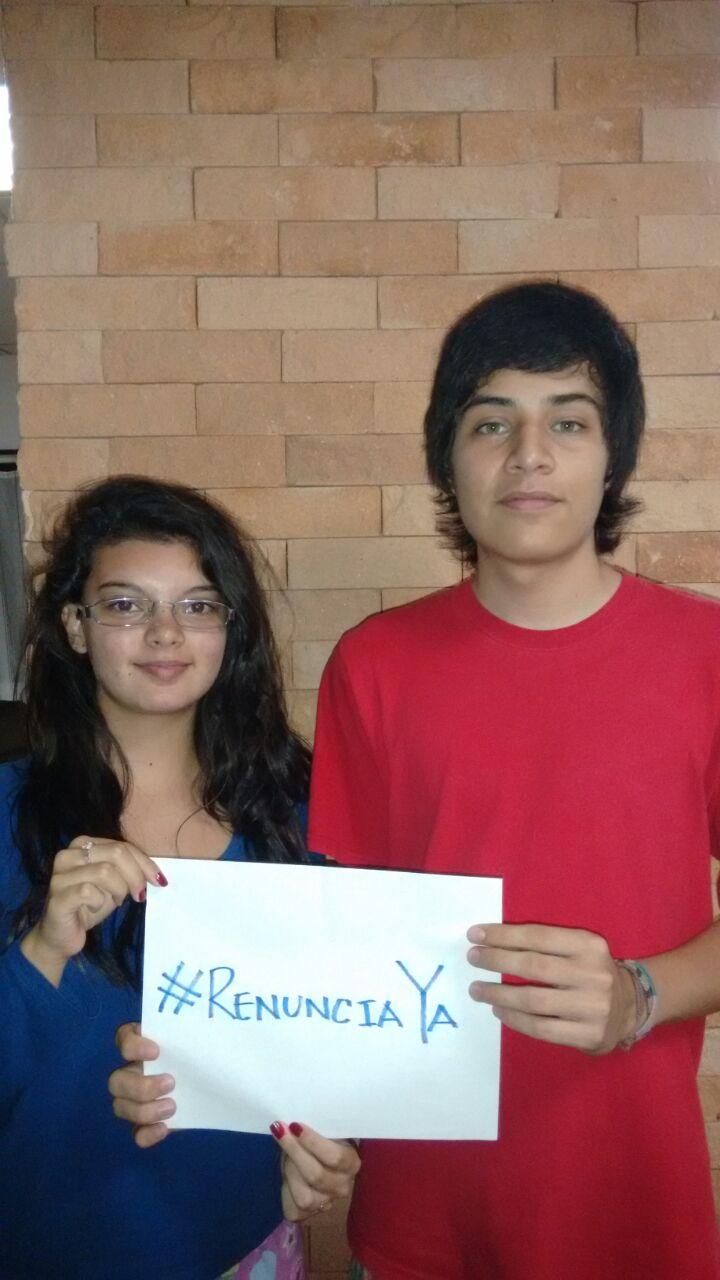

But this case has proved different — the scandal sparked a movement. Last Saturday, a social media-savvy cohort of young Guatemalans was the driving force behind a protest that was larger than any the country had seen in recent memory. Thousands of people, not just students, poured into into the streets of the capital, Guatemala City. Today, crowds are once again expected to march to demand an end to corruption and the resignation of President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti. The protests have largely been organized on Facebook and on Twitter, where a hashtag for the movement has developed: #RenunciaYaFase2, or “Resign already, phase 2.”

Guatemala, with its history of civil war, military dictatorship and, more recently, narco-fueled gang violence, has not had a modern mass protest movement — until now.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” says Ted Fischer, an anthropologist and the director of the Center for Latin American Studies at Vanderbilt University who has been regularly traveling to the country since 1986. “Nothing of this size and scale, and nothing that felt like it had this momentum.”

Iduvina Hernández, director of the Guatemalan Human Rights organization SEDEM, believes the country is at its “most critical moment in many years,” and is in the midst of what she called a “profound crisis.”

Social media has been an important platform, she said, because people can’t trust the government allied broadcast network, which largely ignored last week's protests. And social media has also facilitated new connections and alliances. On May 1, students from private and public universities marched together as part of a “May Day” demonstration to call for the president's resignation.

“That is the first time, in all my life, that I have seen students from the private and the public schools unite,” she says.

Last month, Guatemalan prosecutors, working in collaboration with a UN agency, the International Commission Against Impunity, uncovered a customs bribery network that allegedly included top tax officials and Juan Carlos Monzón, the personal secretary to vice president Baldetti. Monzon disappeared during an official state visit to South Korea and is believed to be hiding out in Honduras, according to AFP.

Guatemalan youth had plenty of reasons to be frustrated already. The government has struggled to control crime — Guatemala had the fifth highest murder rate in the world last year and the economy is not much better. As a UN report bluntly put it “all of Guatemala’s social indicators reflect … widespread poverty and severe inequality.”

“Things are not great there, so there are a lot of reasons for people to be frustrated,” Fischer says. “What’s impressive about this movement is that you actually have people out in the streets demanding this and that is rare.”

One of the people out in the street is 18-year-old Fredy España. Like many of the student protesters, he describes himself as middle class. A student of Mechanical Engineering at the Universidad del Valle University de Guatemala, he first found out about last Saturday’s event when he got an invite on Facebook. As the event page quickly went viral, he grew more excited.

“I get involved because I really feel disappointed with the last years of the government,” España explained in a text via the messaging service WhatsApp. “And I think it’s time to say, together like a country, that we are tired of corruption.”

Five congressmen and a presidential candidate have abandoned the governing party over the customs scandal. President Pérez has said he did nothing wrong and has no intention of resigning. The scandal has been nicknamed La Linea, or the telephone line, for the special number people could call to evade customs duties.

The protests seem likely to continue. Seventeen-year-old high school senior Ana Lucia Laparra, España’s cousin, plans on joining the next big march scheduled for May 16. She’s been actively supporting the movement on Twitter, Facebook and with her friends on WhatsApp, but she doesn’t think social media is the main reason why so many of her peers have decided to protest.

“I think it’s more that we began to think outside the box when we got to know more about our history,” Laparra says. “Now, as young people, we aren’t afraid to express ourselves freely. Guatemala is a country where society has been repressed and older people feel afraid to think differently because they were created, raised in a world where there were many taboos, and under dictatorship and the civil war.”

The May 16 event will be her first protest.

“Now I am old enough to know my rights and obligations and ask for a better future for my country,” she says. “Because I am tired of it always being the same thing, that the people remain silent about corruption in their own government because they are afraid of it.”