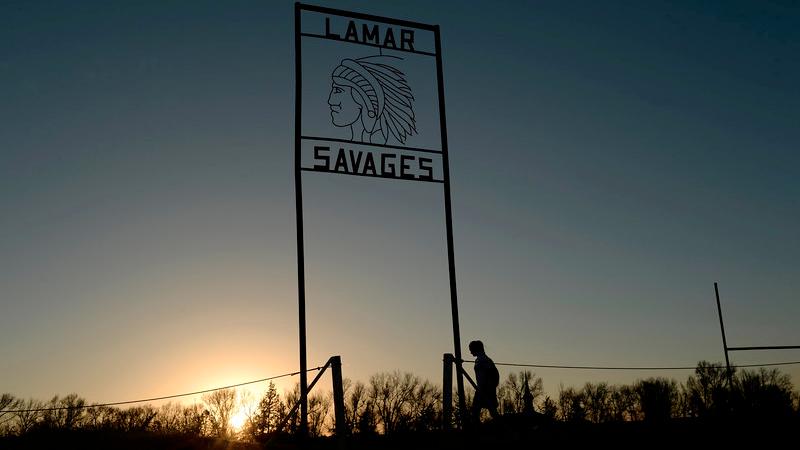

Is it sunset for the Savages of Colorado?

Alina Balasoiu, a junior at Lamar High School, walks back to school after play in a soccer game in the fields behind the school. A bill going through the Colorado Legislature that would require panel approval for mascot and team names. Several Native Americans testified how hurtful it is to have Indian team names, and the Lamar Savages in particular have been singled out for having a name that is considered offensive.

Out here on the Great Plains, it's a savage country. Tornadoes, hail and blizzards can hit without warning. A prolonged drought has pummeled the economy, with dust storms so severe the schools have closed early twice so buses wouldn't be dropping off kids in blackout conditions.

And now Lamar, Colo., finds itself in the harsh glare of the culture wars and in the sights of lawmakers who want to ban the high school's nickname.

"One, two, three, Savages!" members of the Lamar High School track team shout inside Savage Stadium early this week.

Junior Ivan Villasenor struggles to catch his breath after doing two 200-meter sprints back to back, but he was more than willing to talk about the team's name.

"I love the word 'savages,' " he says. "It shows we're never going to give up. We're striving for a goal — and that goal is greatness."

The sentiment is shared throughout this ranching town, 45 miles from the Kansas state line. Faded yearbooks document a team name that has been in use for more than a century and has survived questions in recent decades about whether displaying "Savages" on school uniforms and gym floors is offensive.

The school, which does not identify with any particular tribe, uses a logo of an Indian in a headdress.

One Democratic state representative, Joe Salazar, finds the name repugnant. He is co-sponsoring a bill that would require schools with American Indian names or mascots to get approval from a panel of tribal members or else face steep fines. He says the logo is respectful but the name Savages is not. He predicts it would get the boot.

Even if the measure survives the Democratic-controlled House, it won't make it through the Republican-controlled Senate, according to GOP members.

And that's a relief to Lamar Savages, young and old.

"I raised eight Savages, and they all turned out good," says Dorothy Comer, 72, who manages the Lamar Community Building, where the basketball, volleyball and wrestling teams compete.

"If you go to the high school, you'll be amazed by the pride we have," says Steve Knobbe, 62, a retired teacher who is an assistant football coach for the Savages. "There is nothing negative."

A kaleidoscope

The current Lamar High School, which opened in 1968, sits at the end of Savage Avenue. Student-made metal sculptures, some depicting American Indians, stand guard outside. Inside, the walls are a kaleidoscope of colors as a result of senior class art projects that have included elaborate and sophisticated murals. The Class of 1984 painted a camera with a roll of film spooling from it, an image of an American Indian among the frames. An enormous drawing of an Indian man, courtesy of the Class of 1978, dominates the cafeteria.

Signs taped to the wall advertise yearbooks for sale and Savage Pride. "Some wish for it. We work for it. #SavageNation."

"If we had to change our name, folks around here would be pretty upset," says former principal Allan Medina, who now serves on the school board. "What would we have to do with all our murals? Paint over them? Because I think they're pretty respectful."

As does Superintendent Dave Tecklenburg, who laments that the district three years ago laid off 40 staffers to make ends meet.

When the district surveyed the families of 40 students who weren't returning in fall 2014, the majority cited the economy as their reason for leaving.

The sentiment in town? Lawmakers should focus on those kinds of issues in Denver instead of school mascots.

Passionate crowd

"This is just politics," says 77-year-old Larry Pearson, who worked for the school district for 31 years then served on the school board for another dozen.

He was among a small but passionate crowd of people who showed up Tuesday at the Colorado Welcome Center in Lamar's renovated 1901 train depot to give an impassioned defense of the Savages. Because The Denver Post was coming to town to write about the name, the locals wanted folks in the big city to know where they stood. And if the government wants Lamar to quit using the name Savages, then, by God, it needs to change the name of its Tomahawk cruise missiles and Apache helicopters.

"I was a Savage. My four kids were Savages. I have five grandkids who want to be," says Ken Anderson, 63, who works in the insurance business.

Lamar native Linda Reyher Downey, whose husband once coached the baseball team, graduated in 1969, the first class in the new high school. She says she is a registered member of Choctaw tribe and has "always been very proud to have such an honorable mascot as an Indian chieftain."

But some American Indians who testified in favor of House Bill 1165 say it is never appropriate to use Indian names or images. Elicia Goodsoldier spoke about the psychological impact on American Indian students. She told the committee that Indian mascots are not neutral symbols; rather, they are offensive and they injure students.

Such a sentiment puzzles students at Lamar High, where 25 of the 421 students identify themselves as having American Indian ancestry. Among them is junior Perla Chavira.

"We're high schoolers, and we're trying to be fierce and ferocious," whether it's on the playing field or in the classroom, she says.

Freshman Shania Jo Runningrabbit, a member of the Blackfeet tribe, was born in Lamar.

"We don't use Savages in a derogatory sense," she says. "It's a pride thing."

Salazar says if the school wants to honor American Indians, it should change its name.

The House Appropriations Committee on Thursday approved his bill on a 7-6 party-line vote but took out funding to help schools bear the cost of changing mascots.

An 1898 publication

Cheyenne, Arapaho and Kiowa Indians once roamed what became southeastern Colorado.

It's unclear how long Lamar's nickname has been in use. Tecklenburg said a former superintendent saw a mention in an 1898 publication. The high school's 1910 yearbook used the name in a description of a football game between Lamar and Rocky Ford.

"We proved that we had the right name, for we went into the game like a bunch of savages and showed our strength all the way through, making the score stand 27-0," the yearbook read.

A decades-old poster for the Savages featured a caricatured big-nosed Indian wearing braids and beating a drum, but those images are long gone.

As the American Indian Movement gained prominence in the early 1970s, Lamar took heat for its nickname. The issue would wane then flare up again.

Former US Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Ignacio, who is an American Indian, took up the cause in the early 1990s.

He singled out Lamar.

Crissy Stegman, who graduated from Lamar High in 1996, recalled talking to Campbell about the mascot.

"I told him my grandfather was a full-blooded Cherokee and that I was proud to be a Savage," Stegman says.

Campbell says in a recent interview that his issue is not with the word "savage," where definitions range from fierce to barbaric, but pairing an American Indian image with it.

"I remember when we did a ribbon-cutting at the Sand Creek massacre site," he says. "I said if there were any savages here that day, it wasn't the Indian people."

Neighboring Kiowa County is the site of the horrific massacre of more than 200 peaceful Indians — most of them women and children — by Army Col. John Chivington and his troops in 1864. It's now a national historic site.

Campbell says he believes if a school wants to use the image of an Indian, it should work with a tribe, much the way Arapahoe High School in Centennial has developed a relationship with the Arapaho Nation on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming. Students annually meet with tribal members, and the school's logo was drawn by an American Indian artist.

In Lamar these days, there is talk of reaching out to one or more tribes.

Lamar High junior Rafael Gonzales, who was working out in the Savages' weight room this week, says he can't imagine tribal officials visiting the school and being offended.

"We," he says, "honor their culture."

A longer version of this story appeared in The Denver Post. Where do you stand on this issue? Let us know in our comments section.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!