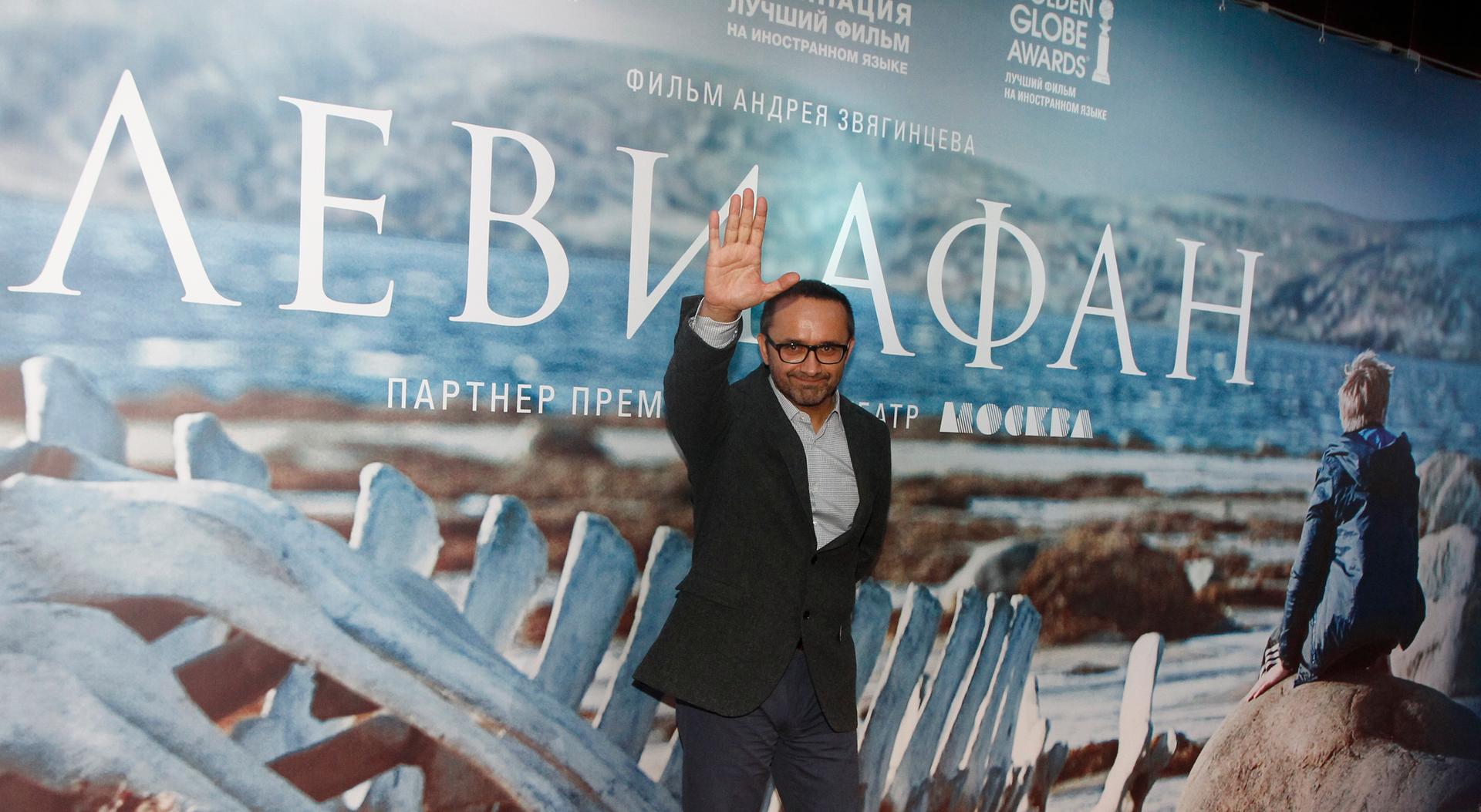

Director Andrey Zvyagintsev poses at the Russian premiere of his film "Leviathan" in Moscow.

Non-spoiler alert: "Leviathan," the film from Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev that offers a bleak, deeply corrupt vision of his country, is creating serious controversy.

"Leviathan," now an Oscar nominee for best foreign film, is loosely inspired by the story of a Colorado zoning dispute that turned violent back in 2004. Zvyagintsev's version moves the story to a picturesque seaside town in Russia's north, and is sprinkled with Biblical allegories from the Book of Job,

The characters lead lives that are perhaps unhappy — and definitely unhealthy. But true misery comes only to those who confront the powers that be. All of the forms of Russian authority — the town mayor, state bureaucrats, the Russian Orthodox Church, the courts, the police, and, by extension, President Vladimir Putin — are in on the fix.

In other words, contact with the state brings its citizens nothing but despair. And in that idea, some Russians see a larger truth. Others only see a hatchet job.

Among the film's biggest critics is Russia's minister of culture, Vladimir Medinsky.

"I find it extremely odd that among the many characters in this film, there is not a single attractive one," Medisnky said in comments to journalists earlier this month.

(Warning: Naughty language in the video below.)

oembed://http%3A//youtu.be/jpawdA34HNk

Medinsky argues the film's depiction of daily Russian life, with its incessant drinking, swearing, and societal and moral rot, panders to Western myths about the country. The film’s release was delayed until just this month over Zvyagentsev's refusal to recut the picture according to new domestic obscenity laws.

Meanwhile, others have piled on: Members of the Orthodox Church have called it blasphemous, and conservative lawmakers argue for the film to be banned outright.

Prizes on the international awards circuit, including a Golden Globe for best foreign film, have only fed the perception that "Leviathan" is celebrated in the West for all the wrong reasons.

"Anything critical of Russia is automatically seen as either another Western attempt to denigrate Russia and the Orthodox Church, or it's the work of some fifth column of Russophobes who are paid by the West," says Alexander Rodnyansky, one of the film's producers.

In a recent interview with the BBC, Rodnyansky argued "Leviathan" has fallen victim to shifting political winds at home, as Vladimir Putin takes Russia on an increasingly conservative and anti-Western course.

"It's not just the officials," Rodnyansky says. "I would say that 'Leviathan' divided Russian audiences in a way that no film has since perestroika times [near the end of the Cold War]. You are either passionately against it or as passionately for it."

In Teribrika, the small village on the shores of the Barents Sea that serves as the backdrop for the film, local deputy Tatiana Tribulina says reactions were mixed during a recent screening.

Everyone loved the way the film captures the northern seascapes, she notes. They loved the cinematography and the music. But the film? A resounding no.

"The film was made in Teribrika, but for some reason everyone thinks it's about Teribrika," she says. "It's not. These are invented characters. The film has no relation to us at all. Our people don’t live like that. We live just fine … just like Russians everywhere.

"Maybe even better than Americans," she adds.

But it's exactly these types of comparisons that give "Leviathan" its power, says journalist Yuri Saprykin. He argues that the film is like a mirror, full of little details that resonate even tthough some Russians may not always care for the view.

"One of the complaints you often hear about the film is 'I don't see myself in that film. That film is not about me or any of my friends or acqaintances,'" he says. "But a lot of films are like that … And the very fact these discussions are happening around this film proves that 'Leviathan' captures something real."

And for all the backlash surrounding "Leviathan," one of the mysteries of the film is that it was funded in part by the state and chosen — actually, selected — by Russia as its official entry for the Oscars.

Saprykin argues the authorities are playing a subtle game. The state doesn't want or need to turn Zvyaginstev and his film into a cause célèbre reminiscent of Soviet dissidents like Alexander Solzhenytsin or Boris Pasternak of "Doctor Zhivago" fame. Instead, the government is playing it both ways.

"At the same time they organize a campaign against the film and saying it was done for the West to blacken Russia's name, they're also giving the film some support," he notes. "And I'm certain that if he wins the Oscar, very high level people in the government will congratulate Zyvaginstev and say it's a big victory for Russian cinema."

Be that as it may, Tatiana Tribulina says the residents of Teribrika have no plans to gather and watch the Oscar ceremony. State television isn't carrying the Academy Awards live this year, and Tribulina doesn't think an Oscar win for "Leviathan" would lead to anything good, anyway.

"Come summer, the tourists will come here and ruin the place," she predicts.

It's a fittingly bleak view on the success of a fittingly bleak film.