These South African men tackle violence against women — starting with themselves

The Mraqisa family, from left, Lindela, son Bukho, daughter Ongeziwe and Nosicelo stands outside their home in Gugulethu Township.

South Africa’s economy under apartheid put huge pressure on black families. Men often left home for months or years at a time to work in mines, or held menial jobs that inflicted daily humiliations. Under those circumstances, it was hard to hold a marriage or a family together.

It's not easy to repair that damaged legacy, but Patrick Godana is trying.

Patrick has the restless intensity you might expect from a former guerrilla fighter. Once a member of the armed wing of the African National Congress, he’s now the media and government relations manager for Sonke Gender Justice in Cape Town.

His life is devoted to fighting violence against women and changing the culture that allows it to happen. In his view, South Africa’s past bred terrible fathers — including his own.

“We were born eight siblings at home,” he says. “I have never seen my father kissing my mother, but I have seen him many times beating up our mother. May her soul rest in peace.”

Patrick's father was a boilerman in a white-owned bakery. He labored in the heat all day, keeping the fire going in the ovens. "He was a hard-working man," Patrick says, "but my mother was subjected to be the kind of a person who was doing all the dirty work for him.”

Patrick remembers his mother waking at four in the morning to heat water for his father's bath, iron his clothes and make his lunch.

He suspects his father's behavior was a reaction to the treatment he endured outside of his home. At work, even the son of the boss called him by his first name, Jim.

“So he was trying to assert power by all means,” Patrick says. “He would speak so rough to my mother and all of us we were made to run up and down. [He was] eight hours at work with no name, no title, no authority. And as a man, especially an African man, he wanted to assert his power and say, ‘Am I still the man?’”

Despite the violence he's endured — he was tortured by the apartheid regime during his days as a rebel fighter — Patrick doesn't want to repeat that cycle, and he wants to prevent other men from doing so. He's passionate about a program Sonke coordinates here called MenCare, which teaches men to be good partners and fathers.

Patrick takes me to visit a couple who have attended MenCare parenting sessions. Lindela Mraqisa is a police officer in Gugulethu, a township outside Cape Town. He’s 33. His wife, Nosicelo Mraqisa, 27, is a stay-at-home mom. They have three small kids, including a baby boy who clambers over their laps while we talk.

Nosicelo says the couple didn’t get along too well in the early days of their marriage. “We would always clash,” she says. “When he says something, I didn't listen. I would just say what I want to say, and when he snaps, then it would be just exchange of words. And we never sat down to talk about things. We'd only fight.”

The fighting involved yelling, not hitting; Nosicelo says her husband never laid a hand on her. But Lindela admits he went into the marriage expecting to get his way. “The way we grew up, we would always be taught that [men] must have the last word,” he says, “[that] whatever I say goes.”

They heard about the MenCare program at their community health clinic and decided to give it a try. Lindela attended a father's workshop and together they attended a parenting workshop. It was 12 weeks of intensive sessions with other couples; 12 weeks of often-sad stories about fathers, including Nosicelo’s.

“I think he loved us,” she says of her dad. “But out of nowhere, he would disappear. He used to work at the mines. He would come home maybe once a year.”

The sessions helped the couple talk to one another. Lindela says the most important thing he’s learned is simply to listen.

“And then from what you've heard, make sense of it,” he says. “And think if you were that person. She also wants to be heard. She also wants to have a say. She wanted to be respected as my equal half, not someone who's just here.”

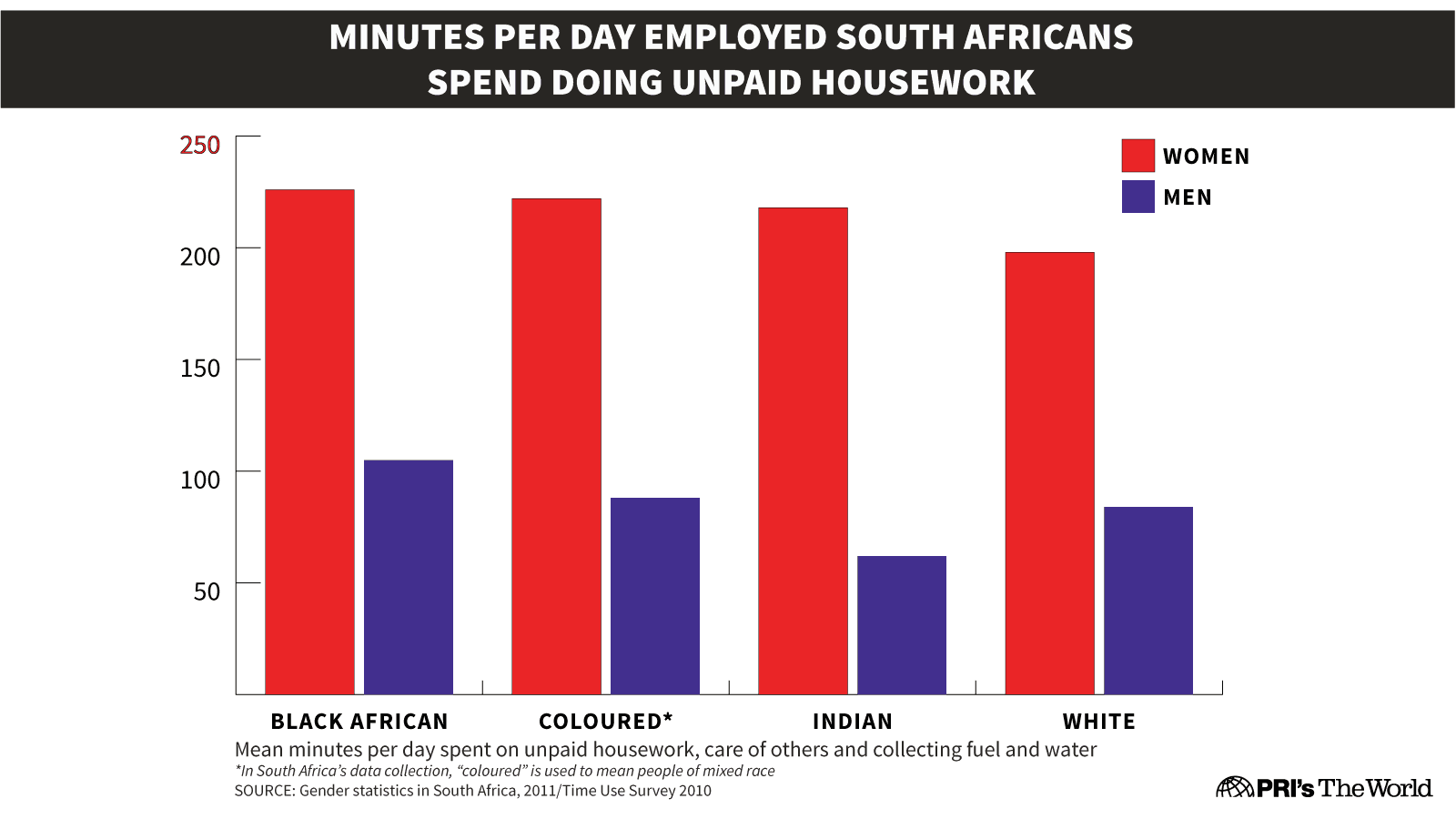

The MenCare program works at all sorts of levels: Coaxing men to talk about their feelings, come to their children's births, begin to share the housework. Before they attended the parenting sessions, Lindela was too embarrassed to do certain things around the house. Nosicelo remembers a time she asked him to do the kids' laundry while she was out.

“He did do the washing,” she says. “But when I came back, the washing was in the basin. I asked him ‘Why didn't you put the washing outside?’ He said ‘I can't! What are people going to say about me putting the washing on the line?”

“It was really embarrassing,” Lindela recalls, “because when I’d go out after that, my friend would tease me all day: ‘Hey man, what's going on? Are you man enough? Is there something she gave you on your food to soften you up?’”

But now Lindela doesn't care what they say. He badgers those same friends to do more to help their own wives. Lindela and Nosicelo make a good poster couple for MenCare. This is exactly the kind of success the activists want to see. Changing the culture, one person, one family, at a time.

Jeb's stories from Cape Town were produced in collaboration with South African journalist Kim Cloete.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?