Training America’s next teachers: Sometimes they learn in the very schools where they’ll teach

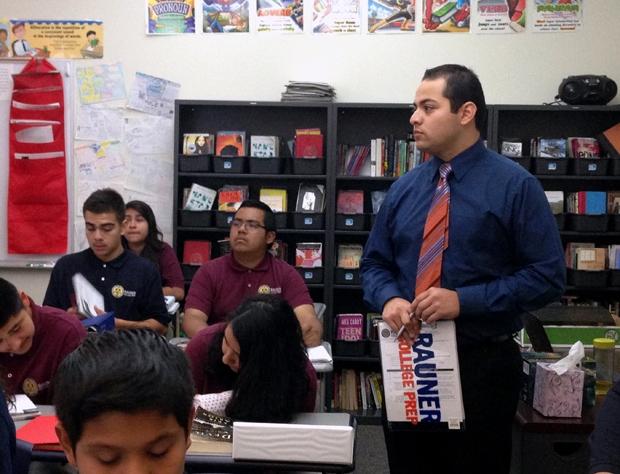

Jose Garcia was in the first graduating class at Chicago's Rauner College Prep, a campus of the Noble Street Network of Charter Schools. That was in 2010 and he's now back as part of a graduate program created by Noble, in partnership with the Relay Graduate School of Education.

Jose Garcia never thought he’d be the one writing directions on the board in room 105.

“I didn’t expect to be here,” he says on the first day of classes at Rauner College Prep, one of the 16 campuses of the Noble Street Network of Charter Schools, Chicago's largest network of publicly-funded, privately-run high schools.

There’s a small sign taped to the lower right hand corner of the board listing a few fun facts about him. Favorite smell? Cilantro. Favorite lunch? Tacos with an horchata. Hidden talent? Playing trumpet. Advice to 9th graders? DO NOT take short cuts.

There’s a whole generation of Joses in Chicago now. Students who were part of a grand experiment launched in the late 1990s. An experiment that bet that public schools free from Chicago Public Schools bureaucracy, with no unions, strict discipline and an unrelenting focus on college, could get more low-income, students of color to succeed.

Now, Jose is now part of a new step in that movement. He is going to be a teacher at his old school. He doesn’t have a license or a degree in education.

For the next two years, Jose will be part of a new graduate program Noble created in partnership with the Relay Graduate School of Education, which is taking a radical new approach to training teachers.

Growing up in the school reform generation

Jose’s story starts across the street from this school in Chicago’s West Town neighborhood two decades ago.

His parents immigrated from small towns near Guadalajara, Mexico in 1986, and landed in this working-class neighborhood and lived with relatives. On December 28, 1991, Jose was born.

By the time he was in grammar school, Jose’s parents bought their own house on Huron and Willard Court, across the street from Carpenter Elementary, a public neighborhood school.

“I literally grew up right across the street from my elementary school,” he says.

It’s at about this time that Jose’s life starts to collide with some of Chicago’s biggest education reforms.

The summer before Jose entered 7th grade, the mayor of Chicago at the time, Richard M. Daley, announced an initiative that would usher in a new wave of school reform. It was called “Renaissance 2010” and the goal was to open 100 new public schools in five years; two-thirds would be charters.

It would eventually close Jose’s grammar school and create his high school.

A high school that would open three blocks from Jose’s childhood home, in the old Santa Maria Addolorata parish school building, and be named after billionaire-venture-capitalist-turned-Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner

It would be a second campus of a school Jose had heard a lot about.

“Everyone in the neighborhood knew about Noble,” Jose recalls. “Everyone wanted to go there.”

Families in Jose’s neighborhood knew Noble was strict, safe, and had a single-minded focus about sending kids to college. The first school opened in 1999, when Jose was just eight years old, after two CPS teachers had become convinced they could run a more successful school than the ones they worked in.

Noble’s early success caught the attention of wealthy Chicagoans, like Rauner, who liked that the school was free from Chicago Public Schools bureaucracy and the teachers union. Jose’s parents simply wanted him to go to college and saw Noble as a way to get him there.

“Once my mom and I heard new campuses were opening up, that was good news because that meant my chances of getting in were a bit higher,” Jose says.

Jose applied to Noble’s lottery and got one of the 150 spots available at Rauner College Prep. But when he was in 8th grade, his parents had decided to sell their house in rapidly gentrifying West Town and move south to McKinley Park. So every day for the next four years, Jose took the El back to West Town to go to high school at Rauner College Prep.

He got decent grades — mostly B’s, a few A’s, he says — and vividly remembers his getting his first detention, which Noble calls a LaSalle. It was the third day of freshman year and he forgot to do part of his homework.

Jose had gone to de facto segregated schools his whole life. His classmates were nearly all Latino through 13 years of school.

When he graduated and went to college at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, he struggled to fit in. Denison’s student body was, at the time, about 80 percent white.

“It was definitely a culture shock for me,” he says. “A lot of students in my shoes were being misrepresented or misunderstood. People just didn’t know how to deal with us.”

Jose almost dropped out of college.

During his first summer home, Jose visited his old high school to talk with the next group of graduates. He remembers being brutally honest, telling them that “college was horrible and everyone’s racist.” But Jose says he got over all of it. He earned a POSSE scholarship that would cover all of his tuition, so he went back, and the next year, he says, things got much better. He found a job tutoring students at a nearby elementary school who were learning English.

He started getting work experience in TV news, interning during the summer at the Spanish-language television network Telemundo. In 2013, he got to work at NBC on the investigations desk. That was his career plan. He would work his way up to a TV news station in a big market and give back to his parents.

‘Oh my gosh, why is she calling me?’

While Jose was away at college, a lot was happening at Noble. Leaders opened a fourth and fifth campus, and then a sixth and seventh. Noble was growing into into a mini-district within the district, now operating 16 schools and counting.

The rapid expansion meant Noble suddenly needed a lot more teachers. But they didn’t want just any teachers. They wanted more diverse teachers. Noble and other charter schools had come under fire for lacking teachers who looked like and could relate to the black and Latino students who went to their schools.

During all four years of high school, Jose only had two Latino teachers. Neither were men.

“Ms. Morales was my Algebra 1 teacher and my Pre-Calculus teacher,” Jose remembers. The other was Ms. Galvalisi, his AP Physics teacher.

Noble also wanted teachers who were familiar with how it runs schools — with a focus on strict discipline and getting into college.

Noble leaders floated the idea of recruiting and training their own teachers and Mindy Sjoblom, the former Dean of Instruction at Jose’s high school and now the principal, led the charge. She knew Noble’s own alumni fit that criteria.

“Literally, the process last year when we dreamed up this idea was going through a list of everybody that we knew was graduating from college this year and thinking, ‘Does this person have what it takes to be a teacher?’” Sjoblom says.

Jose was on the top of her list.

“To myself, I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, why is she calling me?… I thought I had already made up my mind.’” Jose remembers.

He always saw himself getting that job in TV news. To make good money and repay his parents for their years of support. But then, Jose thought, none of that would have been possible if he hadn’t gone to Noble and gotten the POSSE scholarship.

Jose didn’t have any other official job offers and he started to feel a pull to help kids who experienced what he did, both in high school and college.

“I said, you know what, I’m going to go for it.”

And with that, Jose signed up for Noble’s next experiment in school improvement.

First days of school

It’s August 25, 2014 and Jose is about to speak to a sea of 16- and 17-year-olds. It’s apparent he went to Noble, when, on the way to a morning assembly, he pulls his phone out of his front pocket and moves it to his back pocket. “Something that we prohibit is phones visible in the front pocket,” he whispers.

The school’s new principal Jennifer Reid is giving the junior class a pep talk that’s one part “welcome back,” two parts “let’s get down to business.”

“Smart people make it to college, but smart people with character graduate from college and make use of their college degrees for the people around them,” Reid says. “We are not in the business of creating really smart brown people who have college degrees who don’t serve their community. We are not in that business. We are in the business of creating people who care, who work, who are smart, but who also have passion.”

Reid says she knows somebody who is one of those people.

“I need you to give a round of applause for Mr. Garcia.”

Jose tries to explain to a bunch of students, not that much younger than he is, why he is standing in front of them. He says, when he was a student at Rauner, he sometimes felt like college was impossible. But ultimately, he finished.

“I think it is my responsibility to come back to my community, to my neighborhood, so that you guys see that it is possible,” Jose says.

In the classroom, he has no idea what he’s doing yet. He’s winging it.

The only experience Jose has had working with kids so far was tutoring second graders while he was a student at Denison.

He got just two weeks of training over the summer and he doesn’t have a teaching license.

There are other teacher training programs that throw recent college graduates into the classroom with little training. Teach for America trains its recruits for just five weeks over the summer before handing over the responsibility of educating anywhere from 30 to 100 students.

Sjoblom, the woman who recruited Jose, wants him to have a different experience.

Her plan for making Jose into a teacher means he will have to wait a full year before getting his own classroom. It’ll be “a more steady on-ramp into the profession,” she says.

Each one of the 16 people she recruited to teach at Noble will work under licensed teachers in other Noble schools. Jose is paired up with Jillian McDonald, a freshman English teacher. McDonald changed course after an early career in marketing. She got a Master’s in Education from DePaul University and has taught at Noble for five years.

Over lunch, Jose and McDonald talk through a lesson they’ll teach on finding the main idea. They’ll be using an article about Rudy Ruettinger, the Notre Dame football player. McDonald asks if Jose still wants to take over after independent reading time. He does. She says, “Ok, do you want to walk me through how you would approach this?”

Jose says he’ll have the freshman pair up and talk about the main idea. McDonald nods patiently and then asks, “How are they going to read it?”

Jose pauses. “Oh! They haven’t read it yet?” he laughs. McDonald laughs. “No, we haven’t given it to them.” “Um, silently. I’ll have them read it silently,” Jose smiles.

Once students arrive, there are some things that come naturally for Jose. His speaking voice is strong and at one point, he gets a fidgeting boy in the front row to immediately stop playing with his binder with a single look. A “teacher look.”

Those little tricks are not going to be enough. The rest, Jose will learn over the next two years at a graduate school that’s entirely new to Chicago. A graduate school that’s just as green as Jose.

How charters try to build their own teachers

On a Friday afternoon in mid-September, Jose, the graduate student, is sitting in a desk in a room at another Noble school, and he’s not paying attention.

“Good afternoon everybody,” begins Sjoblom, a former teacher at Jose’s old high school and now the dean of this school, the Relay Graduate School of Education in Chicago.

“Very…” she stops and looks at Jose. He looks up from his papers. “Did you guys see me just use one of the strategies today? To get Jose and Yessenia’s attention,” Sjoblom asks the room.

A young woman in the back raises her hand: “The self-interrupt.”

Jose’s graduate school is not a typical graduate school.

It's not affiliated with a university. Like Jose, all of the other teachers enrolled work at Noble schools. There’s no campus, no lectures, no discussions of John Dewey or Rudolph Steiner. Mostly, it’s a lot of practice on how to manage a classroom. At one point, the room full of twenty-somethings stand-up and start reciting an example of a teacher technique they call “the self-interrupt.”

Sjoblom’s mission is to get Jose and the other 15 teachers in this room as prepared as possible. Make mistakes here, not in front of students.

The last hour of class is spent on what Sjoblom calls “scrimmages.” Each teacher-in-training practices a lesson on the others. Jose tries out a lesson on the parts of speech.

“Yessenia, do you know anything about verbs?” he asks a fellow teacher, pretending she’s a student in his imaginary class.

“No,” Sjoblom interrupts from the back of the room.

“‘Yessenia, tell us what you know about verbs,’” she corrects.

Jose continues, moving around the room, focusing on speaking with authority, trying a self-interrupt when one fellow teacher starts tapping a pencil on his desk. When he’s finished, the other teachers snap their fingers in approval and Sjoblom runs down a quick list of suggestions for next time.

The practices are awkward for Jose, but he sees why they’re important.

“I thought, when I was a student, that being a teacher was just natural, like my teachers were up there doing it because they were born with it,” Jose says. “But it was because they had the proper training to do it.”

Related: Global Nation Education

Most of Jose’s teachers were trained through traditional schools of education and picked up classroom management tricks along the way.

Critics of Relay say its style of training boils teaching down to only its most basic elements and is too focused on controlling student behaviors, not on fostering creativity or a love of learning.

But Sjoblom says pondering educational philosophies isn’t going to help Jose and the others in the classroom.

“We don’t want to spend time digging into and debating the theory,” Sjoblom says. “We want to say, ‘Hey here’s what we learned. Here’s what we know about child development. So now what does that mean for my classroom?’”

“Most people enter the teaching profession where they are handed a classroom of kids and we’re like, ‘Well, good luck! Let me know if you need help!’,” Sjoblom says, adding that most new teachers are 22 or 23 and haven’t even had a real job yet.

That approach, Sjoblom says, could easily drive Jose away from teaching.

This story is part of a series originally published by WBEZ. Reporter Becky Vevea spent the last year following Jose Garcia in his first year as a teacher. You can read the entire series here.

Share your thoughts and ideas on Facebook at our Global Nation Exchange, on Twitter@globalnation, or contact us here. Is there a question you wanted answered in this story? Let reporter Becky Vevea know.