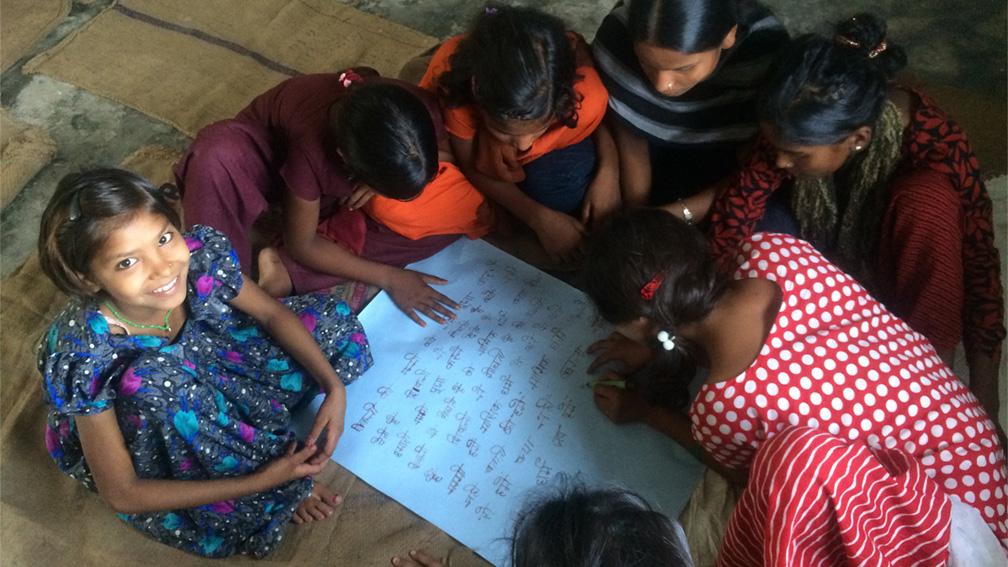

A group of young girls makes a list of questions on menstruation after watching a film about the issue.

Sex education can be a pretty touchy subject in rural India. So anything related to it? Most likely it'll come off as taboo.

And that includes one of the most normal experiences every woman in the world goes through every month: having her period. Shame around menstruation can lead girls to miss or even drop out of school.

The situation is even more heightened at residential schools for girls in Uttar Pradesh. These schools, called Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas, are specifically geared toward girls from minority communities and castes in rural India. Some of these girls have never attended school before; others have had to drop out in the past because their families couldn’t afford school fees, or because they were needed at home to work or help with household chores.

That’s why instructors with the NGO Milaan are especially trying to broach the subject of menstruation at these residential schools. Most of these girls come from poor families, and many of their families live far away in remote areas. And in many of the communities they come from, menstruation remains a subject few people talk about, even woman to woman.

At a Kasturba Gandhi school in Balrampur, a district of Uttar Pradesh, Milaan workers have the students sit in a circle to play a game. In front of them is a plastic, square-shaped bag of sanitary napkins. The game is “hot potato,” and the pads are the potato.

As music plays from a laptop, the girls nervously pass the bag to each other. Whoever is holding the pads when the music stops playing is supposed to say something, anything she can think of, that might be related to menstruation.

But when the music stops the first time, the girl with the bag of pads in her hands is speechless.

As the game continues, it’s clear the girls have never before been encouraged to talk about their periods. The music starts and stops, but still, no one dares to speak. Finally, the fourth time the music stops, the hot potato ends up slipping last from the hands of 13-year-old Jyoti Tripathi. She stands up, dusts the back of her red-and-white polka-dotted salwar kameez and mutters two letters: “MC.”

“MC” is the term the girls — and many Indians — use for “menstrual cycle.”

Earlier, before the game, Jyoti told me the MC was a complete mystery to her until about a year ago. That’s when she got her period for the first time. No one in her family, not even one of her five sisters, had prepared her for its arrival, which happened when she was at school.

“I went to the bathroom and blood started coming out, and I thought, ‘What is this?’” she says. “I went to my friends and told them what had happened, and they said it was the MC and to go get a pad,” she says.

Jyoti got the supplies she needed. But when she talked to her teacher about what was going on, she got some confusing advice. She recalls her female teacher telling her: “It’s bad blood, and if you eat anything sour like pickles, then it will create more difficulties. So when the MC comes, don’t have sour things.”

That might sound strange, but it’s kind the thing Milaan field workers encounter all the time. Dhirendra Singh, Milaan’s co-founder and CEO, says there are logical reasons for the pickle taboo: Many people believe spicy foods should be avoided during that time of the month. And in rural India, the fermented vegetables called pickle are often the spiciest food in the house.

“So how do you make sure kids don’t touch the pickle? You say ‘don’t touch the pickle or else the pickle will go bad,’” Singh says.

Part of what Milaan workers do to challenge this myth is to encourage young girls and women to be open to discussing menstruation and all these taboos.

“It’s all about education, right?” Singh says. “You want to be able to give our girls the ability to question what prevails them. And to find answers to those questions.”

The understandings surrounding these taboos also have different meanings given India’s patriarchal culture. Women were always in the secondary position to men in rural communities, and the view that period blood is impure became rampant because of that bias against women.

Neelam Singh, a gynecologist in Lucknow who also does education and advocacy around menstrual issues through the NGO Vatsalya, says the myths and practices surrounding periods also go back to a blunt kind of birth control.

“People thought [girls] would get pregnant once they have started [their periods]. So it was actually to limit their mobility,” she says. “So that is how they were not allowed to go to school, not allowed to talk to boys, they were not allowed to play around … It was taken as dirty. So that is why they would [also] contaminate good things.”

Back at the Kasturba Gandhi school, most girls are horribly confused about their MC because no one has really explained it to them well. This also leads to a feeling of shame about what they’re going through. Jyoti confessed she hadn’t even told her family she had gotten her period. She didn’t see the point.

“I don’t understand all of this,” Jyoti says of the changes her body is going through. “Whatever my friends and teacher have told me, that’s all I know.”

The Milaan workers are trying their best to take care of those questions. After the hot potato game finishes, the girls gather in front of the chair where the laptop sits. The instructors use it to show a short film made by UNICEF called “Paheli ki Saheli,” or “Friend of the Riddle.”

The film follows the story of a young girl who’s just gotten her period. When she sees blood stains in her underwear, she asks her friends if she’s going to die. Her friends say what’s happening is normal, and they start speaking in riddles, like: “What type of relative is this, whom we have to welcome once a month, which makes us anxious about all kinds of changes in our body?”

Watching the girls here watch the film is like a scene from a movie itself. Some sit with mouths hanging open, others smile shyly. A couple of teachers watch the film as well. Everyone pays attention.

The film’s a hit with Jyoti. “I didn’t know that the blood comes from the uterus, and I wasn’t aware that when the egg settles in the uterus and doesn’t get released, that only then does a woman get pregnant,” she says. “I didn’t know this.”

Yet understanding the changes her body is going through is not really enough. She’s trying not to make it a big deal, but already she’s looking around and seeing what else is lacking at her school.

“It’s just that the bathrooms have been a problem,” she says. The Kasturba Gandhi school had two toilets meant to serve 100 girls and their teachers. Neither of them are in great condition.

Amit Kumar Ghosh directs the National Health Mission in Uttar Pradesh, which runs a range of healthcare programs in the state. He says that tracking conditions across the state’s schools — which number more than 100,000 — is part of the government’s “administrative challenge.”

“This is a state of around 210 million people, so this is the largest state in the country. Every sixth Indian lives in UP [Uttar Pradesh],” he says. “Our challenges are great … and our systems may not always be robust.”

The state government has its own programs on menstruation, which include employing Accredited Social Health Activists to work on the ground in local districts and distribute sanitary napkins. The state government is also planning to build incinerators in schools to help dispose of pads.

But that should just be the beginning, says Milaan’s Dhirendra Singh. He sees menstrual education in India as the intersection of several issues, and a pivotal time for girls to learn how to advocate for themselves and each other.

“We have to bring the women’s rights lens when we look at menstruation. Because, in the majority of the scenarios when we work with adolescent girls, this is the first time in which they’re actually having to negotiate something for themselves,” he says.

And if that can happen, maybe the start of the dreaded “MC” won’t be so bad after all.