Putin abolished daylight savings time and Siberians are grumbling about ‘eternal winter’

One of my favorite songs by beloved Russian rock band Kino is called City:

The chorus goes:

"I love this city,

But the winter here's too long,

I love this city,

But the winter here's too dark."

Well, this year, when Vladimir Putin decided to abolish daylight savings time, winter across Russia just got a lot darker. One news report put it this way: "On Sunday, Russia switches to wintertime and stays there. Forever."

That means more sunlight in the morning, less sunlight in the afternoon. And in parts of Siberia, where the clocks were turned back two hours instead of just one — a very early start to the day.

"So the way it is now, the day starts two hours earlier," says Anya Krushelnitskaya, who grew up in the eastern Siberian city of Chita. "What it means also is that the sun goes down and it's barely after 4 o'clock in the afternoon."

In order to make sure people were getting the most out of those sunny mornings, the official workday in Chita was also shifted.

"The local government workers — it's a sizable community — now have to start their day officially at 8 a.m., not 9 a.m. as they used to," Krushelnitskaya says.

Maybe not a tragedy to some, but it was one of the things that pushed the residents of this Siberian city over the edge. Last month, hundreds of them turned up in the town's Lenin Square — yes, it's still called Lenin Square — to protest the decision. Pretty remarkable for a conservative place like Chita.

"It's normally a very passive and politically placid town, and for a public rally to happen in Chita and to draw 500 people — this is very unusual," Krushelnitskaya says.

I can empathize. If there's one thing that would get me out of bed for a protest when it's only eight degrees outside, it's the threat of — having to get out of bed even earlier in the morning.

So why did Putin decide to plunge Russia into what some have described as "eternal winter"? One official reason given was health. According to a sleep expert quoted by the government news agency TASS, "Dark mornings have a worse effect on people's state of health than dark evenings."

But some people saw a darker subtext here. Back in 2011, when Dmitri Medvedev was president, he controversially switched Russia to permanent daylight savings time.

"We've gotten used to moving the hands of the clock back and forth every spring and autumn," Medvedev said in his announcement, "and gotten used to being unhappy about it. It disrupts our biorhythms. It aggravates us."

Well, Medvedev's decision may have aggravated Putin. The Washington Post read Putin's move to abolish daylight savings time as a Medvedev smackdown.

But is the health issue valid? I mean, is it really true that waking up early makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise? Or is this just something Benjamin Franklin put out there to make late risers feel bad? Arcady Putilov at Novosibirsk's Institute for Molecular Biology and Biophysics studies sleep cycles.

He told me that according to his research, after controlling for factors like sleep duration, early birds aren't any healthier than night owls. But Putilov's research also shows that when it comes to wake-up time, people tend to think everyone else is like them — or should be.

But what if Russia's time-shifting isn't about political one-upmanship or health? What if it's something more innate?

Scientists have long known that our circadian rhythms are influenced by genes, gender and age. We tend to wake up earlier as we approach our senior years. Okay. Medvedev is 49, and Putin is 62. Chances are Putin's getting up earlier — and he thinks everyone else should too.

If you ask Camilla Kring, she'll tell you it isn't fair. She's president of the B-Society, a group based in Denmark that's is dedicated to promoting the rights of late risers, or "B People" as chronobiologists call them.

"The problem in today's society is that the society only supports the "A" person, you know, the person who prefers to get up early and go to bed early."

Kring told me we shouldn't equate early rising with qualities like responsibility and diligence. Late risers aren't slackers and according to her research, there are actually more of them.

Still, government officials in Chita at first were less than sympathetic to those B people who opposed the new 8 a.m. start time.

"The comment from the spokesperson of the gubernatorial office was those government employees who do not like the new order can jolly well just leave their job," Krushelnitskaya says.

But a few weeks, and 60,000 signatures on an online petition later, the government's position seemed to soften. Recently, the governor, Konstantin Ilkovsky, promised to evaluate the impact of the new time regime next year. He even hinted they might just get their hour back.

Perhaps eternal winter will not be so eternal after all.

—–

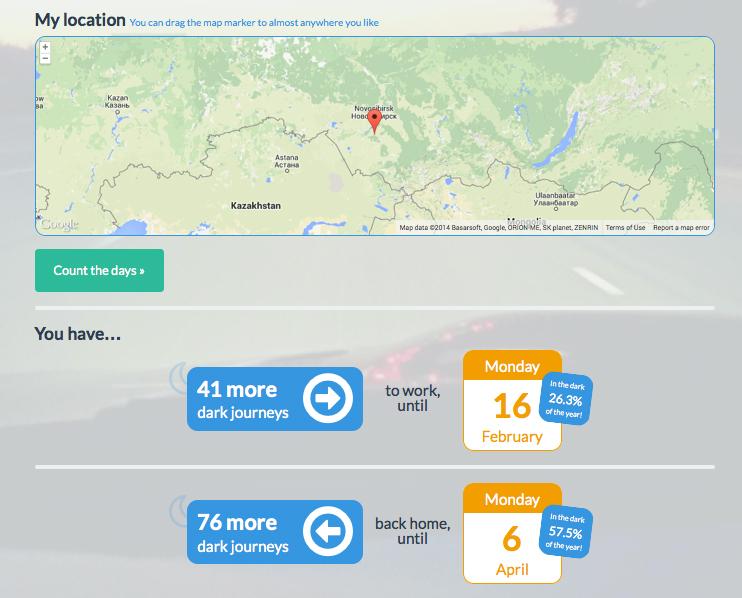

Editor's Note: We wondered what the daily commute was like for people living in Siberia and found this online "dark mornings" calculator. It's an app that tells you how many more days you'll be commuting in the dark if you leave work at a certain time. We dragged the marker to Novosibirsk, the capital of Siberia, and got 76 more days for a departure time of 6 p.m. Here's how it looks.