Her Mom is Jewish. Her Dad is Palestinian. She sees both sides

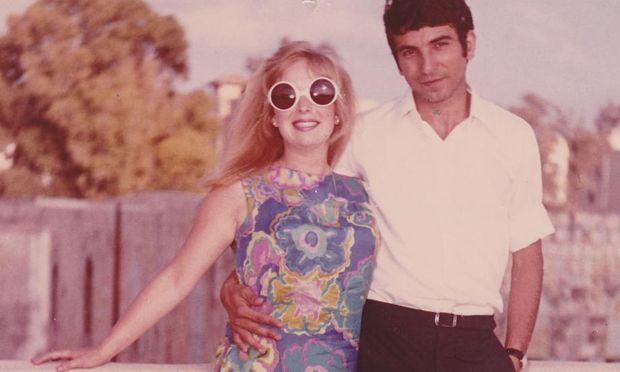

Claire Hajaj’s parents, Deanne and Mahmoud Hajaj, honeymoon in Israel in 1969.

As the daughter of a Palestinian father and a pro-Israel Jewish mother, Claire Hajaj's expertise on the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is personal.

On her mother's side, the shadow of Russian pogroms and Auschwitz's death camps cuts through her family history. Her father's family was in Jaffa when Zionist paramilitary groups arrived with tanks and mortars. They eventually fled the region, losing their family home.

Her new novel, "Ishmael's Oranges," is based on the story of her parents, who met and fell in love at at British university in the summer of 1967, as the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians raged on.

"They met in the UK during the summer of love in 1967 — by then we'd already had the Suez crisis, we'd already had the Six-Day War, and the memory of '48 was still incredibly fresh," Claire says. "But for these two people, they didn't see the conflict in each other. They just saw two people who understood each other fundamentally in ways that other people didn't."

Claire says both her father's and mother's families were shocked and confused by their relationship at first, even though both families were not very religious.

"For the Muslims, Mohammed himself had a Jewish wife, so it wasn't completely unheard of that Muslim might marry a Jew," Claire says. "For them, I think they eventually came to think after the initial shock, 'Well, maybe she will be absorbed into our society and the children will by default be Muslim — they will be Palestinian because their father is.' For my mother's side, I think it was more difficult."

Claire says her father had stayed in Israel after 1948, and adopted many aspects of Israeli culture — he had an Israeli passport and even spoke Hebrew.

"He probably was about as Jewish as a Palestinian could be," Claire says.

Though her parents did unite in love, both still had deep-seated stances on this decades-long conflict, something that reached into Claire's own world.

"For as long as I can remember, I've been on the front line of seeing these two communities tearing themselves apart," she says. "I have the curse, if you like, of being able to empathize with both perspectives. That's a very, very confusing place to be."

Claire says, in many ways, both narratives of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are incredibly similar.

"We have two people who are both obsessed with a story of loss, a story of conflict, of hate, of being driven out of homes, of having families scattered to the winds, of trying to rebuild their lives, and of looking back in pain and fear," she says. "This is the story of the Palestinians and the story of the Jews. I've heard both stories bitterly, angrily told to me throughout my childhood. How on Earth is a person supposed to choose between these stories?"

Claire says she cannot choose.

When she was 5, her mother explained the divide within her family, and the huge issues that separated her mother and father.

"Since then, I have asked myself who is right and who is wrong and what does justice mean — what would be the right thing to do?" she says. "I'm not sure that now I have an answer."

Claire says finding resolution and peace should not focus on righting all of the wrongs of the past and starting over from the beginning.

"That is simply not a possibility," says Claire. "I would prefer, rather than to talk about justice, to talk about what we can do now not to make sure that our ancestors get justice, but that our children have peace, freedom and security."

Though Claire would like both parties to find a middle ground, her own parents could not resolve their differences in the end. They divorced after 25 years.

"Their identities certainly played a role — they were two people who drifted further apart in their political identities the longer they were married, rather than closer together," she says. "Maybe that was inevitable, given the horrendous attrition that has surrounded both societies from '67 to today. Obviously there were personal reasons too — the end of a marriage is never, ever simple."

While her parents' marriage did not work out, Claire says she does believe there is still hope for the Israelis and Palestinians, something that she is trying to convey in her new book.

"It's a cliché to say, but there is always hope," she says. "If there is hope for these two peoples, it exists in the will of two societies to live in peace.

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program where you are invited to be part of the American conversation.

As the daughter of a Palestinian father and a pro-Israel Jewish mother, Claire Hajaj's expertise on the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is personal.

On her mother's side, the shadow of Russian pogroms and Auschwitz's death camps cuts through her family history. Her father's family was in Jaffa when Zionist paramilitary groups arrived with tanks and mortars. They eventually fled the region, losing their family home.

Her new novel, "Ishmael's Oranges," is based on the story of her parents, who met and fell in love at at British university in the summer of 1967, as the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians raged on.

"They met in the UK during the summer of love in 1967 — by then we'd already had the Suez crisis, we'd already had the Six-Day War, and the memory of '48 was still incredibly fresh," Claire says. "But for these two people, they didn't see the conflict in each other. They just saw two people who understood each other fundamentally in ways that other people didn't."

Claire says both her father's and mother's families were shocked and confused by their relationship at first, even though both families were not very religious.

"For the Muslims, Mohammed himself had a Jewish wife, so it wasn't completely unheard of that Muslim might marry a Jew," Claire says. "For them, I think they eventually came to think after the initial shock, 'Well, maybe she will be absorbed into our society and the children will by default be Muslim — they will be Palestinian because their father is.' For my mother's side, I think it was more difficult."

Claire says her father had stayed in Israel after 1948, and adopted many aspects of Israeli culture — he had an Israeli passport and even spoke Hebrew.

"He probably was about as Jewish as a Palestinian could be," Claire says.

Though her parents did unite in love, both still had deep-seated stances on this decades-long conflict, something that reached into Claire's own world.

"For as long as I can remember, I've been on the front line of seeing these two communities tearing themselves apart," she says. "I have the curse, if you like, of being able to empathize with both perspectives. That's a very, very confusing place to be."

Claire says, in many ways, both narratives of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are incredibly similar.

"We have two people who are both obsessed with a story of loss, a story of conflict, of hate, of being driven out of homes, of having families scattered to the winds, of trying to rebuild their lives, and of looking back in pain and fear," she says. "This is the story of the Palestinians and the story of the Jews. I've heard both stories bitterly, angrily told to me throughout my childhood. How on Earth is a person supposed to choose between these stories?"

Claire says she cannot choose.

When she was 5, her mother explained the divide within her family, and the huge issues that separated her mother and father.

"Since then, I have asked myself who is right and who is wrong and what does justice mean — what would be the right thing to do?" she says. "I'm not sure that now I have an answer."

Claire says finding resolution and peace should not focus on righting all of the wrongs of the past and starting over from the beginning.

"That is simply not a possibility," says Claire. "I would prefer, rather than to talk about justice, to talk about what we can do now not to make sure that our ancestors get justice, but that our children have peace, freedom and security."

Though Claire would like both parties to find a middle ground, her own parents could not resolve their differences in the end. They divorced after 25 years.

"Their identities certainly played a role — they were two people who drifted further apart in their political identities the longer they were married, rather than closer together," she says. "Maybe that was inevitable, given the horrendous attrition that has surrounded both societies from '67 to today. Obviously there were personal reasons too — the end of a marriage is never, ever simple."

While her parents' marriage did not work out, Claire says she does believe there is still hope for the Israelis and Palestinians, something that she is trying to convey in her new book.

"It's a cliché to say, but there is always hope," she says. "If there is hope for these two peoples, it exists in the will of two societies to live in peace.

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program where you are invited to be part of the American conversation.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!