Could this building be the first place to house a church, synagogue and mosque under the same roof?

An initiative in Berlin seeks to build a single building that will house a church, a synagogue and a mosque — in an effort to promote religious tolerance.

More than 1000 years ago the cultural movement of monotheism and the so called "peoples of the book" split into the three main faith groups that remain to this day. Jews, Christians and Muslims.

Ever since, global history has been dominated by disputes among them. A new crowd-funded project out of Berlin, called "House of One," aims to promote religious tolerance by imagining and building a modern space for all three groups to worship peacefully and learn from one another. The project will make religious history as the first building to house a synagogue, a church and a mosque under a single roof.

Wilfried Kuehn, the German architect who won the House of One design competition, says if you look back far enough, you'll see all three religions have common ground.

"Having all three religions actually in one building is of course new and so we don't look at a typological model to follow. The three have all their own traditions," Kuehn says.

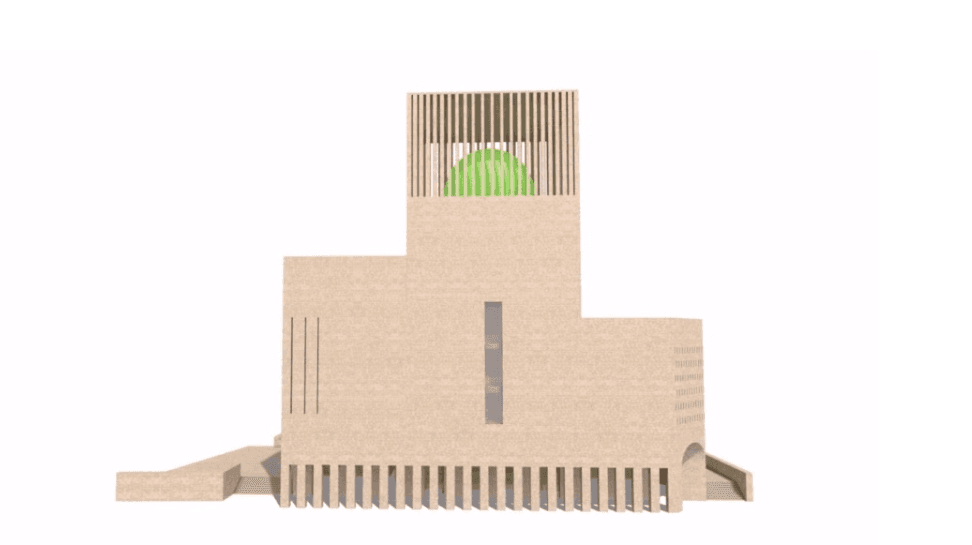

The House of One will be a monumental brick building with a striking square tower and large windows. Inside, the thre faiths have their own individual spaces, equal in size and height.

"There is an idea of equality and still a high degree of specificity and diversity. So to the outside, you don't think, 'oh, this is a typical mosque, this is a typical synagogue, or this is a typical church, because all symbolism like menorahs and crosses and the like are missing. Whereas, inside of each of the three spaces, you then have the proper attributes and space being made for each of the religious performances," Kuehn explains.

Of course, these three monotheistic religions have their own divisions. Kuehn says religious leaders involved in House of One are eager to promote inclusivity by embracing the more orthodox and more liberal sects.

"So, this is a Protestant, Lutheran community that is here in Berlin, but there is a big openness to share with other confessions, the more conservative and the more liberal ones. And there is of course our interest in making this project for the secular civil society that in Berlin is very developed and all those people who do not go to a church or a mosque or a synagogue regularly," Kuehn adds.

His design includes a central area, where all three faiths and anyone from the public can come together to learn from each other and work on community initiatives.

"The fourth space is very important because we very much believe that the whole building is a place for the secular, for people to encounter and get in touch with faiths and what the idea of faith might mean even in a post-religious world," he adds.

The project, set to be completed by 2018, is a bold step toward religious tolerance. While Kuehn and others involved in House of One recognize the challenges, they are confidant the project will have a positive impact. For the project to succeed, though, it will need considerable contributions. So far, they've raised just .06 percent of the 43 million euros they believe they need for the project.

"We participated in this competition exactly because we thought instead of thinking about identity as secluded and isolated, you could think about it in terms of something that has to do with encounter, with relation," Kuehn says.

More than 1000 years ago the cultural movement of monotheism and the so called "peoples of the book" split into the three main faith groups that remain to this day. Jews, Christians and Muslims.

Ever since, global history has been dominated by disputes among them. A new crowd-funded project out of Berlin, called "House of One," aims to promote religious tolerance by imagining and building a modern space for all three groups to worship peacefully and learn from one another. The project will make religious history as the first building to house a synagogue, a church and a mosque under a single roof.

Wilfried Kuehn, the German architect who won the House of One design competition, says if you look back far enough, you'll see all three religions have common ground.

"Having all three religions actually in one building is of course new and so we don't look at a typological model to follow. The three have all their own traditions," Kuehn says.

The House of One will be a monumental brick building with a striking square tower and large windows. Inside, the thre faiths have their own individual spaces, equal in size and height.

"There is an idea of equality and still a high degree of specificity and diversity. So to the outside, you don't think, 'oh, this is a typical mosque, this is a typical synagogue, or this is a typical church, because all symbolism like menorahs and crosses and the like are missing. Whereas, inside of each of the three spaces, you then have the proper attributes and space being made for each of the religious performances," Kuehn explains.

Of course, these three monotheistic religions have their own divisions. Kuehn says religious leaders involved in House of One are eager to promote inclusivity by embracing the more orthodox and more liberal sects.

"So, this is a Protestant, Lutheran community that is here in Berlin, but there is a big openness to share with other confessions, the more conservative and the more liberal ones. And there is of course our interest in making this project for the secular civil society that in Berlin is very developed and all those people who do not go to a church or a mosque or a synagogue regularly," Kuehn adds.

His design includes a central area, where all three faiths and anyone from the public can come together to learn from each other and work on community initiatives.

"The fourth space is very important because we very much believe that the whole building is a place for the secular, for people to encounter and get in touch with faiths and what the idea of faith might mean even in a post-religious world," he adds.

The project, set to be completed by 2018, is a bold step toward religious tolerance. While Kuehn and others involved in House of One recognize the challenges, they are confidant the project will have a positive impact. For the project to succeed, though, it will need considerable contributions. So far, they've raised just .06 percent of the 43 million euros they believe they need for the project.

"We participated in this competition exactly because we thought instead of thinking about identity as secluded and isolated, you could think about it in terms of something that has to do with encounter, with relation," Kuehn says.