Oops! Major miscalculations and brilliant blunders aren’t unheard of in science

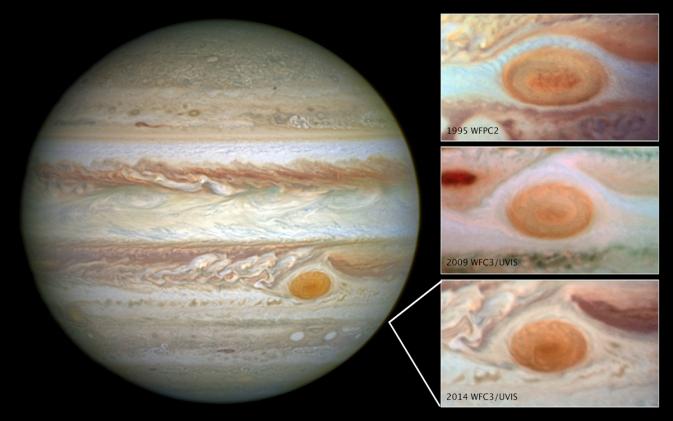

Ever since its main mirror was fixed, the Hubble Telescope has been sending spectacular images back to Earth. Images of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope over a span of 20 years, show how the planet’s trademark spot is getting smaller.

The French railway company recently received the first of 2000 new train cars it ordered. Great news for the travelling public, right?

Turns out, not so much. The railway found out the cars they've purchased and started to receive are just a few inches too wide for many French rail platforms. Oops.

The French railway blunder is estimated to be a $70 million miscalculation.

We wondered if there are other cases where a little error has proved to be very expensive, or changed the course of science.

Mario Livio is an astrophysicist who's thought about this problem a lot too — he's the author of a book about it, Brilliant Blunders, and he blogs at A Curious Mind. He draws an important distinction between brilliant blunders as opposed to stupid blunders, like forgetting to measure the train platform.

"By brilliant blunders I mean blunders that don't come because you're being sloppy or because you don't think about it enough, or you're inexperienced or you're in a haste," he says. "Brilliant blunders are those that come because people are trying to think outside the box, they try to think in unconventional ways, and guess what? When you think outside the box sometimes you make blunders. Also very often these could truly lead to breakthroughs."

Here's an example of a brilliant blunder: Charles Darwin, who introduced the idea of evolution, did not have an accurate understanding of genetics. Nobody did during his lifetime, Livio says. "He did not understand that with the theory of genetics that he used, which was that you mix the qualities of the mother and the father like you would mix. If that were true, natural selection could never have worked, because you would have diluted all the good characteristics, like you do with a gin and tonic. He didn't understand that but he did, once it was pointed out, that blending heredity just couldn't work, and eventually he found the true theory of genetics that Gregor Mendel discovered."

Another famous example of a blunder has to do with the Hubble Telescope. It's famous for its beautiful space images, and has been a great success for NASA. But it had a very rocky start. The first images sent back were fuzzy because of a tiny little error in the design of the main mirror. It was too flat. It wasn't off by much — only 2.2 microns (about 1/50th the thickness of a human hair), but just enough to put the mission in jeopardy. Fortunately, scientists managed to fix the problem in 1993, using an instrument called the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement. This fixed the error in the main mirror, by matching it in reverse.

Livio says the case of the Hubble Telescope was definitely not a brilliant blunder. "The mirror of the Hubble was supposed to be absolutely the best mirror ever made. It was. It was the best polished mirror ever. Except that it was polished to the wrong specifications. It would be like your optometrist giving you glasses with perfect lenses, but they're not the number that you want. So in that case the mirror was a little bit too flat around the edges," he says. "But that was enough to make the telescope not have the kind of sharp vision that we all hoped for."

So the mistake was corrected, says Livio, thanks to engineers and scientists who thought of ways to essentially put spectacles on that telescope. And Hubble is, to this day, still sending back spectacular images.

Hubble is helping to reveal a new phenomenon on the planet Jupiter. Some recent NASA Hubble Space Telescope observations show Jupiter's Great Red Spot is approximately 10,250 miles across. That's interesting because historic observations as far back as the late 1800s gauged the storm to be as large as 25,500 miles across. Scientists say the spot is shrinking — by 580 miles per year — changing its shape from an oval to a circle.

Livio says the example of Hubble illustrates an idea basic to science. "This is how science and in fact all creative processes really work. They work in a zigzag path, it’s not a straight march to the truth. Many times you hit upon blind alleys or you have false starts and you have to go back. You also have to allow for serendipity. Many discoveries were made serendipitously." In the medical profession for example, Livio cites many medications that were discovered by researchers They were looking for medications for tuberculosis and they found something instead that works for depression. So you have to allow for all of this."

As for the major French railway blunder, apparently construction work has already started to reconfigure station platforms to accommodate the new trainsets. The work will allow new trains room to pass through. But officials say that there are still 1,000 platforms to be adjusted. "That's definitely not a brilliant blunder, but it's as silly a blunder as they come," Livio says.

Have you blundered recently?

The French railway company recently received the first of 2000 new train cars it ordered. Great news for the travelling public, right?

Turns out, not so much. The railway found out the cars they've purchased and started to receive are just a few inches too wide for many French rail platforms. Oops.

The French railway blunder is estimated to be a $70 million miscalculation.

We wondered if there are other cases where a little error has proved to be very expensive, or changed the course of science.

Mario Livio is an astrophysicist who's thought about this problem a lot too — he's the author of a book about it, Brilliant Blunders, and he blogs at A Curious Mind. He draws an important distinction between brilliant blunders as opposed to stupid blunders, like forgetting to measure the train platform.

"By brilliant blunders I mean blunders that don't come because you're being sloppy or because you don't think about it enough, or you're inexperienced or you're in a haste," he says. "Brilliant blunders are those that come because people are trying to think outside the box, they try to think in unconventional ways, and guess what? When you think outside the box sometimes you make blunders. Also very often these could truly lead to breakthroughs."

Here's an example of a brilliant blunder: Charles Darwin, who introduced the idea of evolution, did not have an accurate understanding of genetics. Nobody did during his lifetime, Livio says. "He did not understand that with the theory of genetics that he used, which was that you mix the qualities of the mother and the father like you would mix. If that were true, natural selection could never have worked, because you would have diluted all the good characteristics, like you do with a gin and tonic. He didn't understand that but he did, once it was pointed out, that blending heredity just couldn't work, and eventually he found the true theory of genetics that Gregor Mendel discovered."

Another famous example of a blunder has to do with the Hubble Telescope. It's famous for its beautiful space images, and has been a great success for NASA. But it had a very rocky start. The first images sent back were fuzzy because of a tiny little error in the design of the main mirror. It was too flat. It wasn't off by much — only 2.2 microns (about 1/50th the thickness of a human hair), but just enough to put the mission in jeopardy. Fortunately, scientists managed to fix the problem in 1993, using an instrument called the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement. This fixed the error in the main mirror, by matching it in reverse.

Livio says the case of the Hubble Telescope was definitely not a brilliant blunder. "The mirror of the Hubble was supposed to be absolutely the best mirror ever made. It was. It was the best polished mirror ever. Except that it was polished to the wrong specifications. It would be like your optometrist giving you glasses with perfect lenses, but they're not the number that you want. So in that case the mirror was a little bit too flat around the edges," he says. "But that was enough to make the telescope not have the kind of sharp vision that we all hoped for."

So the mistake was corrected, says Livio, thanks to engineers and scientists who thought of ways to essentially put spectacles on that telescope. And Hubble is, to this day, still sending back spectacular images.

Hubble is helping to reveal a new phenomenon on the planet Jupiter. Some recent NASA Hubble Space Telescope observations show Jupiter's Great Red Spot is approximately 10,250 miles across. That's interesting because historic observations as far back as the late 1800s gauged the storm to be as large as 25,500 miles across. Scientists say the spot is shrinking — by 580 miles per year — changing its shape from an oval to a circle.

Livio says the example of Hubble illustrates an idea basic to science. "This is how science and in fact all creative processes really work. They work in a zigzag path, it’s not a straight march to the truth. Many times you hit upon blind alleys or you have false starts and you have to go back. You also have to allow for serendipity. Many discoveries were made serendipitously." In the medical profession for example, Livio cites many medications that were discovered by researchers They were looking for medications for tuberculosis and they found something instead that works for depression. So you have to allow for all of this."

As for the major French railway blunder, apparently construction work has already started to reconfigure station platforms to accommodate the new trainsets. The work will allow new trains room to pass through. But officials say that there are still 1,000 platforms to be adjusted. "That's definitely not a brilliant blunder, but it's as silly a blunder as they come," Livio says.

Have you blundered recently?