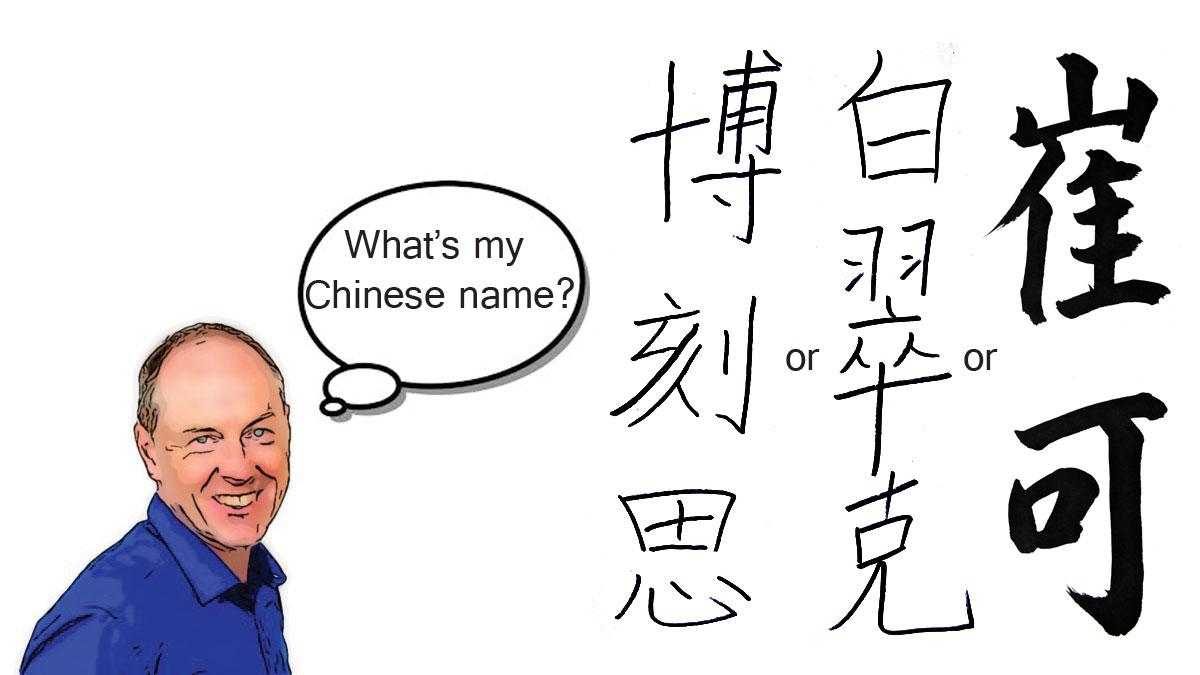

I have been given three Chinese names. Which one should I use?

People with English names sometimes take Chinese names. In fact, some expats in China consider a local name to be as important as a mobile phone number. It’s a must-have.

I don’t live in China, but I’ve been learning Chinese for a few years. Many of my fellow students have Chinese names. I decided that it’s high time I got one. Or three.

Three? It’s an insurance policy: China is full of westerners with abandoned Chinese names that have been tried out a few times on the locals—and failed. In the real world of the China street, they look or sound…weird.

So, I needed a Plan B. And C.

My first Port of Call was Boston’s Chinatown, where I go once a week to wrestle with the Chinese language.

Wenjing Li, my teacher, grew up in Shanghai. And this is what she came up with when I asked her to give me a Chinese name: 博刻思 (Bo ke si).

Wenjing Li, my teacher, grew up in Shanghai. And this is what she came up with when I asked her to give me a Chinese name: 博刻思 (Bo ke si).

There’s a nice lilt to that (listen to the audio above). It has a passing resemblance to my English name, which Wenjing says is all you need. Mandarin and English have such different phonetic systems that it’s pointless to try to force one language to sound like the other. You’d end up with one of those weird names.

Bo, the first syllable, means plentiful. But it might also imply a certain, shall we say, seniority, which Wenjing tells me is appropriate, “because you are older than me.” I ask her if it’s a name for an old person. Not necessarily, she says. Just someone who’s been around the block, and seen a few things.

The second and third syllables—ke and si—mean constantly, and thinking or considerate.

Wenjing has thrown in some wordplay too. The first two syllables bo and ke, pronounced differently, mean podcast. Very clever. She’s also included a potential banana skin in the final syllable, si. Pronounce it the wrong way with the wrong tone, and it sounds like the word for to die.

I tell her that it’s fitting that Chinese teacher gives me name that demands that I get my tones right.

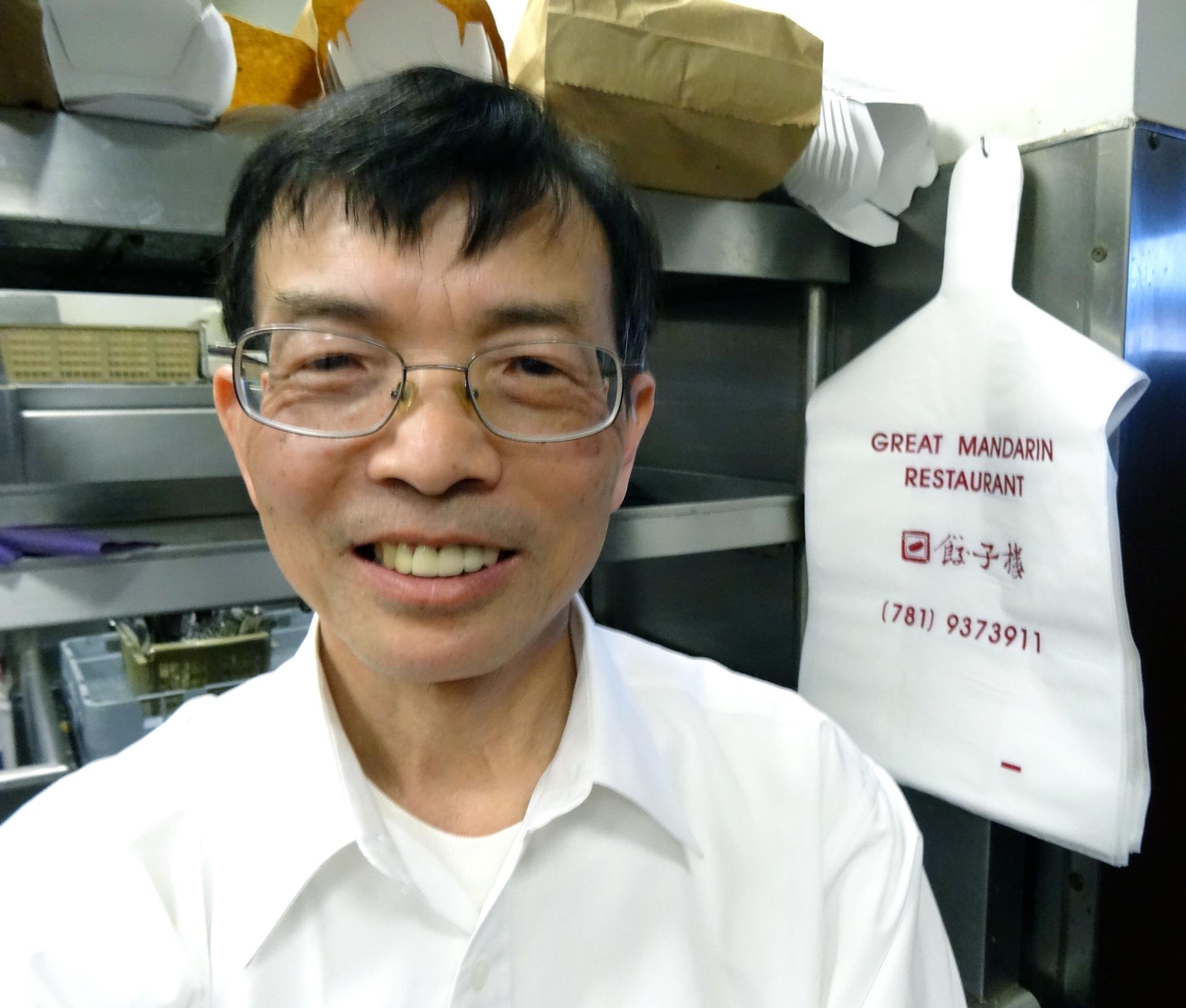

For my second name I go to meet Tony Huang at the Great Mandarin Restaurant in the Boston suburb of Woburn.

Tony is the co-owner, and he’s the father of a friend of mine. He was born and raised in Taiwan, and here’s his name for me: 白翠克(Bai cui ke).

Bai cui ke has some similarities to Bo ke si. Both play off the sound of my English name; they’re both three syllables, also like my English name; and they both include a ke, albeit different ones. But Tony’s name is assembled according to totally different principles: numbers and elements.

Numbers have traditionally played a key role in Chinese names. Older generations of parents would visit a fortune teller with date and time of birth of their child. The fortune teller would then assign a name based on a series of calculations involving, among other things, the number of strokes it takes to write the name in Chinese characters.

For my name, Tony didn’t need to go to a fortune teller. “I went to the fortune teller website,” he says.

I have trouble following all the calculations that Tony is doing. He leafs through page after page of notes. He has spent hours checking charts in books and on websites so he can be confident that my name is sufficiently auspicious.

I have trouble following all the calculations that Tony is doing. He leafs through page after page of notes. He has spent hours checking charts in books and on websites so he can be confident that my name is sufficiently auspicious.

The character stroke count of Bai cui ke is 26, which, Tony tells me, has both good and bad points. (It depends on a bunch other stuff, which you can read about here.)

When Tony points out a couple of aspects of the math that are “bad,” I ask him if he’s giving me a bad name. He says of course not, though I have trouble following his reasoning. There are apparently issues with the number of strokes of the first and second syllables combined (19) as well as the second and third (21).

But Tony knows what he’s doing. He’s configured things so that the name’s negative aspects indicate bad times for me in my 30s. I’m older than that—as Tony says, who cares what my name says about the past? From my mid-40s on, it’s all wealth and happiness.

There’s one more problem. Because the last two characters add up to 21, I apparently may not have a good relationship with my boss. We may just have to live with that.

I now have two names that I love. I may not need another Chinese name but I’m getting greedy. I want one.

I visit a friend, artist and calligrapher Wen-hao Tien. Wen-hao grew up in Taiwan and she lives now in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“I like to find names that are a little vague and are humorous,” she says.

No stroke calculations here. Just intuition—and the look and sound of the name.

“You strike me as a very energetic person," Wen-hao tells me. "Sporty. Somehow the sound of Cui and Patrick is a good fit.”

“You strike me as a very energetic person," Wen-hao tells me. "Sporty. Somehow the sound of Cui and Patrick is a good fit.”

Cui is pronounced “tsway.”

Wen-hao continues: “Actually, there’s a famous rock singer, his name’s Cui Jian.”

How can I resist?

Wen-hao decides that like Cui Jian, the rock star, my name will have just two characters: 崔可 (Cui ke). “Ke means doable, OK, achievable,” she adds.

She paints the characters on a sheet of paper. She asks me what I think. I tell her I like it but I don’t have trained eye for these things.

“Oh, I think it looks pretty cool,” says Wen-hao.

Listening back to these interviews, I hear myself laughing—much more than usual. It’s giddy getting a new name. And judging by the laughter from Wenjing, Tony and Wen-hao, it must be giddy giving one too.

I realize now how much thought goes into giving someone a Chinese name, so much more than the other way round—calling someone Lucy or Lily or Tony. Tony tells me a Chinese waiter will change his English name if that name is already taken at his workplace.

As for my Chinese names, I’m not going to pick one, at least for now—I like them all. So American of me: spoiled for choice.