Al Qaeda hopes to exploit the plight of Myanmar’s embattled Muslims

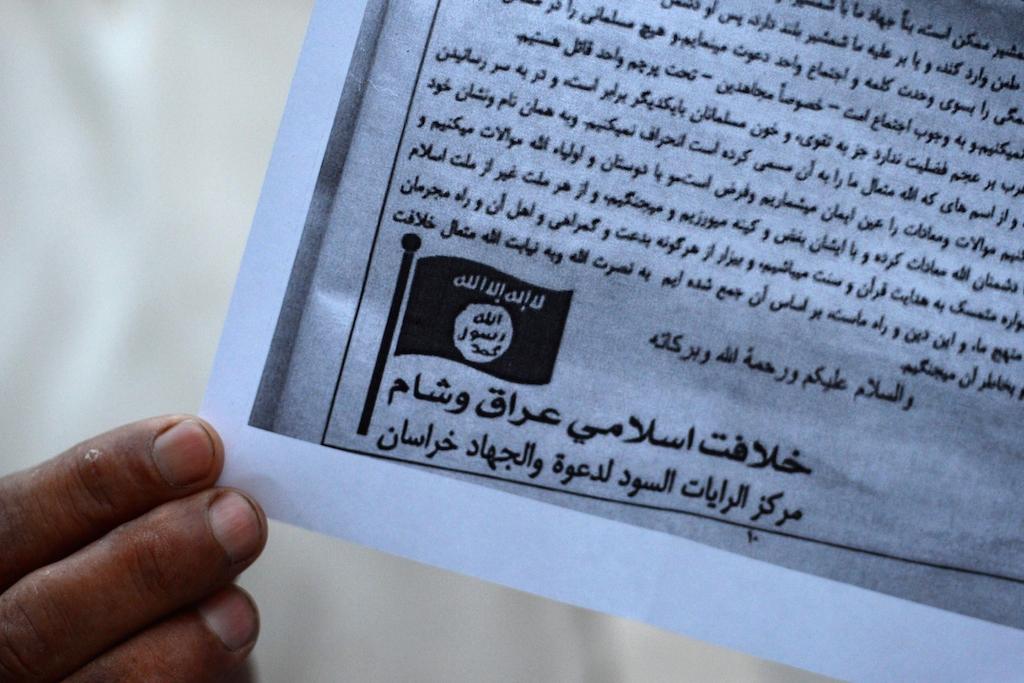

A Pakistani man holds a pamphlet, allegedly distributed by the Islamic State (IS), on Sept. 3. The following day Al Qaeda announced a new South Asia front to “wage jihad” in neighboring India, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Al Qaeda’s global influence has been eclipsed by the rival terror group.

BANGKOK, Thailand — Myanmar’s Rohingya people have been hacked to death, driven from their homes and quarantined in grubby camps. Many are shrunken from malnutrition and disease.

But while most see their condition as a tragedy, Al Qaeda sees opportunity.

From obscurity, the Rohingya plight has in recent years exploded into an international scandal. No country will claim them as their own. Though about 800,000 Rohingya inhabit the western shores of Myanmar, the Buddhist-led government there labels them foreign invaders from Bangladesh. Vigilantes have purged them from cities using arson and murder. Human Rights Watch calls this bloody exodus “ethnic cleansing.”

The Rohingya also happen to be Muslim.

For Al Qaeda, their suffering is a convenient call to arms, especially now that the terror consortium — losing global attention to the Islamic State — is struggling to develop a new offensive in South Asia.

This new scheme will seek to “erase the border drawn by the British to divide the Muslims of South Asia,” said Ayman al-Zawahiri, the successor to Osama bin Laden, in a video announcement released in early September.

The bearded commander wants Muslims in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Myanmar to unite and form a Muslim caliphate. He also sprinkled in a Sunni prophecy about Muslims one day conquering India as a precursor to the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who appears as a prophet in the Quran.

Among the countries mentioned by Al Qaeda’s commander, one sticks out: Myanmar, formerly titled Burma, a Buddhist land of golden temples and barefoot monks.

Al Qaeda has long had deep roots in Pakistan. It can already claim weak affiliates in Bangladesh, a 90 percent Muslim country, and far-flung parts of India, home to the world’s second-largest Muslim population.

But Al Qaeda has no known allies encamped in Myanmar, a nation that seldom received overtures from the terror group (or its partners) prior to the Rohingya crisis.

A range of extremist groups have since offered their help. The strongest statements come from the Pakistani Taliban, an Al Qaeda ally. They promise that “we haven’t forgotten you” and “we will take revenge of your blood.”

Al-Zawahiri insists the Al Qaeda expansion will offer a “cool breeze for the hapless and weak.” But the mere suggestion of Al Qaeda infiltration among Rohingya could justify even harsher treatment against the beleaguered Muslim group.

“The worst thing that could happen to the Rohingya is they’re suspected of having a wing affiliated to Al Qaeda,” said Sidney Jones, director of the Indonesia-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict. “It’s doing Muslims in Myanmar no courtesy to make this announcement.”

Myanmar is already rife with strange anti-Muslim conspiracy theories. Among them: They’re flush with Middle Eastern oil money, they get cash rewards for seducing Buddhist maidens, and they plot to overrun the country.

The theories are as groundless as they are dangerous. As these rumors have gained steam, attacks on Muslim quarters in a dozen-odd cities across Myanmar have killed hundreds in recent years.

Myanmar’s largest Islamic advocacy group wasted no time in condemning al-Zawahiri’s offer. The Burmese Muslim Association called Al Qaeda “morally repugnant” and vowed loyalty to the nation of Myanmar.

The Rohingya families herded into squalid camps aren’t compelled by the convoluted politics of global jihad. They are simply trying to survive.

But for global jihadis, Rohingya communities look like fertile ground for expansion.

Those seeking to paint Rohingya society as a tinderbox of radicalism can point to various Rohingya armed factions that have come and gone in recent decades. But they have always been pathetically small, according to most accounts. And they’ve always been subservient to larger militant groups in Bangladesh, namely an Al Qaeda-linked outfit called Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami.

Even their jihadi friends have treated the small pool of Rohingya militants like cannon fodder. Those funneled to the Afghanistan front via Bangladesh “were given the most dangerous tasks in the battlefield: clearing mines and portering,” according to a report by Myanmar expert Bertil Lintner.

The number of Rohingya militants is currently “so small you can count the number of people in their ranks on your fingers,” said Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy, an analyst with the independent Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi.

Still, she worries that Al Qaeda may finally manage to seed radicalism among bitter young Rohingya men. “They don’t care about global jihad,” she said. “But if Al Qaeda were to offer their support, they’d take it lock, stock and barrel.”

That potential support — if it ever actually materialized — would come from a terror network in decline. Al Qaeda now appears weaker in comparison to the Islamic State, which began as a mere Al Qaeda branch. It has since swelled into a well-financed force controlling large parts of Syria and Iraq.

This turn of events has Al Qaeda struggling to defend its title as the world’s most fearsome terror group. Their attempted expansion into South Asia looks like an effort to play catch up. “That’s got to be the factor driving this announcement,” Jones said. “It’s so clear Al Qaeda has lost ground.”

The potential for extremists to enact a massive caliphate over South Asia is hard to take seriously. The scattered Al Qaeda allies in India and Bangladesh are currently held in check by vigilant armies.

As for the Rohingya, they are well under the thumb of Myanmar’s army. And though rumors of Rohingya militants have swirled for years, it is telling that none emerge to defend them in their darkest hours, when families are violently purged from their homes.