Spanish town claims: We invented Coca Cola

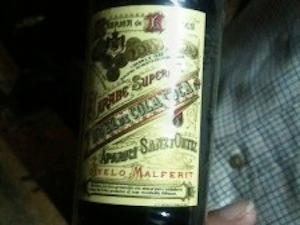

Photo of a bottle of Cola Coca liquor from the early 20th Century. (Image by Gerry Hadden)

This story was originally covered by PRI’s The World. For more, listen to the audio above.

Coca Cola celebrates its 125th anniversary this year. The soft drink giant has much to celebrate. In 1886 it was serving nine cokes a day, out of a single soda shop in Atlanta.

Today the world consumes more than a billion cokes a day, according to a Coca Cola spokesman. Credit for coke’s secret recipe goes to a pharmacist named John Pemberton. But if you ask around a certain tiny village in southeast Spain, people tell a different story. The folks in Ayelo say they invented coke first.

Take Pablo, for example, one of Ayelo’s two policemen. “Thanks to our town, he said on a recent day, “you Americans were able to market Coca Cola all around the world.”

Pablo’s — and Ayelo’s — extraordinary claim is a mix of legend and circumstantial evidence, and requires some explaining. It starts where Pablo the policeman was standing: inside the 126 year old Fabrica de Liquores, or the Liquor Factory.

It’s a family run distillery that makes liquors with anis, strawberry, raspberry, as well as a sweet, dark syrup with a slight vanilla finish. The name: Cola Coca.

The year it was first concocted, according to company records, was 1884. That’s two years before Coca Cola.

JuanJo Mica runs the family distillery now. He’s fourth generation, 72 years old, nearly retired himself. On a recent afternoon he was sitting behind his desk in his dark office.

Philadelphia Prize

‘My great great uncle took his cola coca syrup to America that same year -1884 — And won a prize at a fair in Philadelphia,” he said. “Supposedly, the Americans tried it, liked it and two years later their soft drink, Coca Cola, was born.”

The unspoken assumption is that coke’s founder, the American John Pemberton, must have somehow gotten his hands on some Cola Coca, copied it, flipped the name, added carbonated water and, well, the rest is history.

But Coca Cola’s in-house archivist in Atlanta, Phil Mooney, said he doubted the veracity of the Ayelo legend, but that it didn’t surprise him either.

“We have had at various points in time claims from places like Scotland and India that the formula originated there,” he said in a phone interview. “One of the great things about having a secret recipe is that these sorts of stories pop up periodically.”

Despite Coke’s denial, Ayelo residents insist the coincidences are just too uncanny: at nearly the same moment in history, an ocean apart, nearly identical syrups appear and with practically the same name.

And the story doesn’t end there. According to Ayelo lore, Cola Coca and Coke crossed paths again, in the 1940’s. Coke was trying to enter the Spanish market, but couldn’t because of trademark laws, said JuanJo Mica. He said Coke had to buy his Cola Coca name first because of the similarity.

He said Coke paid his family about $1,700 — which at the time seemed like lot of money.

“My ancestors probably thought coke was just another soft drink that would disappear after a year or two,” he said. “And we’d get the name back. Coke still wasn’t famous and we didn’t know how popular it would become. If you know that a drink is going to sell by the millions then you ask for, say, .005 percent of sales, for example. Instead of settling for $1,700.”

Cola Nut Coca

Mica had no paperwork to prove the sale ever happened. The Coca Cola Co. says it has no record of the deal either. But the Liquor Factory did change the name of its award-winning drink from Cola Coca to Cola Nut Coca around that time. And they added a bit of alcohol.

Around town, Cola Nut Coca still sells well. At a local café one morning a waitress recommended sprucing up one’s coffee with the liquor.

“The people love it,” she said. “And the smell? I get drunk just inhaling it. And I don’t even drink.”

Taste aside, Cola Nut Coca’s ingredients are secret, just as are those used to make the, well, “real thing.”

At the Liquor Factory, JuanJo Mica obliged a reporter’s request and opened an old steel safe from which he pulled out a recipe book.

The recipe book — dated 1881 — to 1951.

It looked like something your grandmother might have kept. The yellow pages were stained and dog-eared. Everything was handwritten. Mica said he was training his oldest son to take over this business.

“If my boy has questions about a certain mix of ingredients,” he said, “I’ll just taste it and tell him to add this or that. I know all the recipes by heart. My son still has to consult this recipe book.”

Mica leafed through the book, unworried about outside eyes. The writing was barely legible anyway, and in a local dialect called Valenciano. The Coca Cola Co. takes decidedly stricter security measures with its formula, according to Coke’s Phil Mooney.

“The only thing we’ll say, we will confirm that it is in a vault in downtown Atlanta.”

The recipes for both colas remain under lock and key, each as mysterious as the other. No wonder the legend of Ayelo survives, 126 years on.

——————————————————————————-

PRI’s “The World” is a one-hour, weekday radio news magazine offering a mix of news, features, interviews, and music from around the globe. “The World” is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI and WGBH Boston. More about The World.