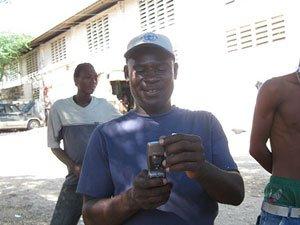

Mobile banking flourishes in Haiti

Photo of a cell phone user in Haiti (image by todkat03 (cc:by-nc-sa))

This story was originally covered by PRI’s The World. For more, listen to the audio above.

By Sabri Ben-Achour of station WAMU

In a small church near St Marc, a small, elderly woman taps intently on a cell phone. With just a few strokes, Lydia Paul receives 60 gourdes — that’s about $1.50.

But it didn’t go to her bank account — she doesn’t have one, and she can’t afford one. It went to her phone. The phone is a bank account. You don’t write checks, you send text messages. This is mobile money.

Haiti isn’t known as a leader in finance or technology. But some of the country’s poorest residents are leading the way to new system of cell phone-based banking.

Kokoévi Sossouvi is in charge of economic recovery for the aid group, Mercy Corps, which is operating in Haiti. Sossouvi has been crisscrossing the countryside, from one packed town meeting to another, explaining how the cell phone banking works.

“We’re trying to give people access to financial services, so they can save money, have a safe way to store their hard earned cash, so they can make transactions,” Sossouvi said.

At a standing-room only crowd at one meeting, Sossouvi asks, “Is there anyone here who has a cell phone?”

About half the crowd yells out: “Yes.” Mobile phones are common in Haiti. About 40 percent of people have one, but only 10 percent have bank accounts. They’re considered expensive, and not worth the trouble for small amounts of money.

Using cell phones to transfer funds will make things much simpler for Haiti’s small merchants, according to Sossouvi. She said they’ll be able to move their inventory around much faster.

“You can phone your suppliers and say, send this to me on the next TapTap, here’s your money, I’ll pick it up and have my sale,” Sossouvi said. “It’s just going to make commerce simpler.”

But all of this is very new. Alexandre Adeline and Dorcent Larousse are merchants. They sell the basics — rice, peas, oil, and some extras, like soap and press-on nails. Alexandre keeps her cash in a box on the floor. Not very secure, but at least she can see and feel it. The money on the phone thing makes her nervous.

“What if we collect all these electronic bonds and the bank goes out of business?” Adeline asked.

Larousse has his doubts too. He says, sometimes when you talk on the phone, you hear the lines cross. Could that happen with the money?

Sossouvi of Mercy Corps said these concerns are completely understandable and that in the training, they tell people that their money is going to be transferred safely through the phone. Sossouvi said:

They turn around and say to us ‘it better come out of that phone!’ ‘My money better come out of that phone! I don’t know what that story is but my money better come out of that damn phone!’ And then the second time they cash out, they say ‘is there any chance I can keep some money on the phone because it’s actually kind of convenient.’

And it’s more secure than cash, said Charles Duthard, who sat in the front row of one of the town meetings.

“When you have cash, somebody can rob you if they see what you have in your hand,” Duthard said. “But this way nobody has any idea how much you have.”

And even if someone takes your phone, they won’t have your personal identification number.

Mercy Corps is partnering with Voila, Haiti’s second largest cell phone network, and Unibank, one of the country’s largest banks to offer the mobile money service. The banks hope it can get more money circulating through the banking system.

The government could conceivably use it to make tax collection more efficient. And Mercy Corps has its own reasons for wanting to shift to mobile money. Project manager Andrew Lucas said the group hands out 20,000 emergency food vouchers a month.

“It takes a lot of time to physically hand out the vouchers, and there’s a lot of tracking for fraud, and there’s a lot of follow up, so I also saw mobile money as an easier way to cut down a lot of time and expense,” Lucas said.

Under the pilot program, Mercy Corps “deposits” about $40 a month into each person’s cellphone savings account — and they can use their phones like debit cards at a few local stores. If all goes well, mobile money is expected to go commercial soon. Charles Duthard said it reminds him of when mobile phones came to Haiti.

“Back when I was younger I had family all over the little islands, and the only way to communicate with them was to record tapes and send them the tapes and that’s how they would hear from me,” said Charles Duthard. “Now I can pick up a phone and give them a call.”

That changed his life, and he thinks mobile money might too.

PRI’s “The World” is a one-hour, weekday radio news magazine offering a mix of news, features, interviews, and music from around the globe. “The World” is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI and WGBH Boston.