Scientist finds beauty in search for elusive dark matter

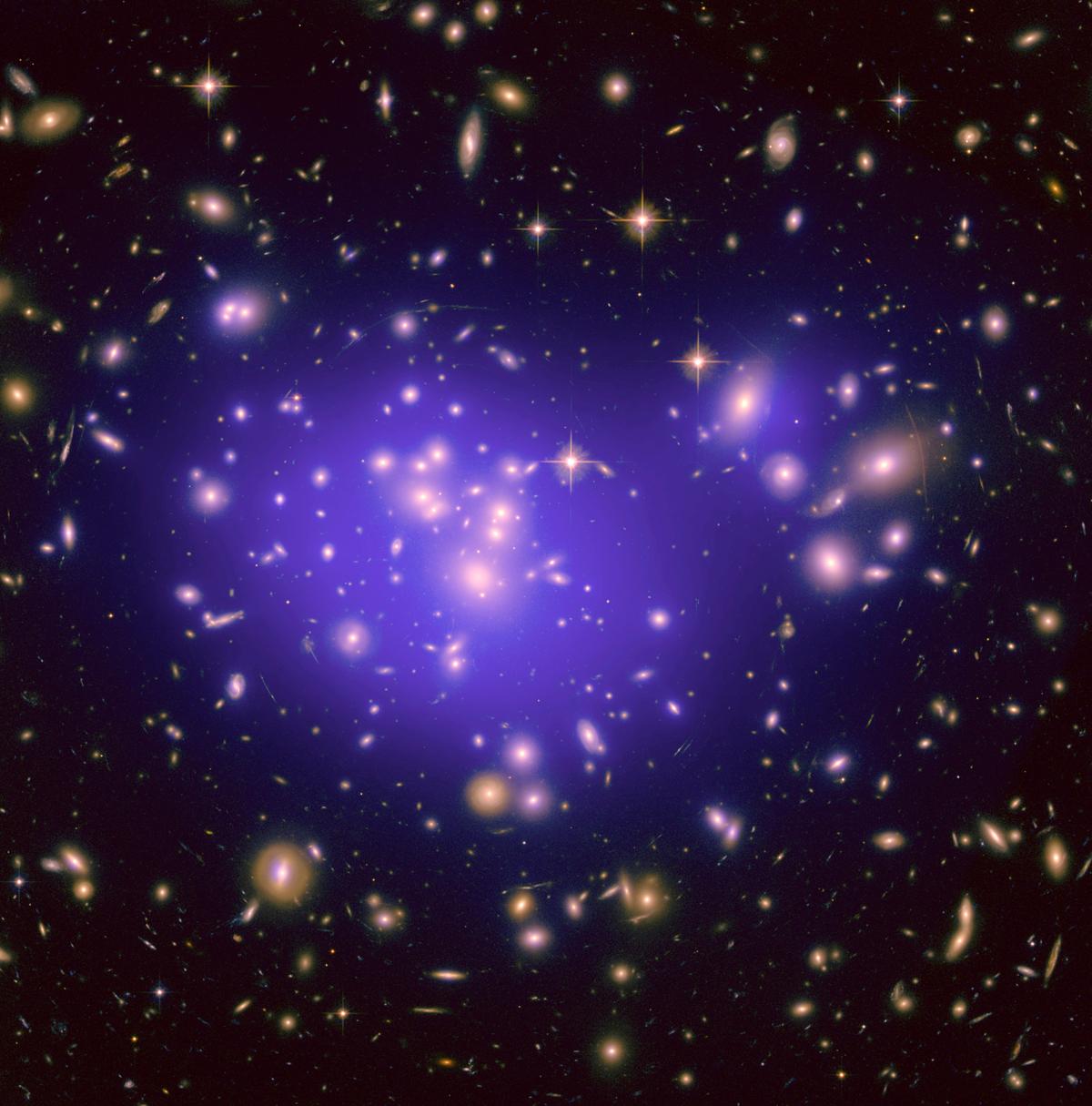

Dark matter is believed to make up some 95 percent of the universe. (Photo by NASA via Wikimedia Commons.)

Right now, one of the biggest races in science is the search for dark matter.

Experimental physicist Elena Aprile heads a research team at Columbia University trying to get one step closer to finding it.

“It’s really very very scary to know that, after all these years of civilization, we still don’t know 95 percent of our universe,” Aprile said. “It makes you feel very small.”

Her detectors are stainless steel cylinders that are filled with liquid xenon gas cooled to about -150 degrees Fahrenheit. When the working model is buried in a mile-deep chamber, she hopes to catch a glimpse of dark matter in that highly controlled environment.

But the detectors are more than just equipment for Aprile. She’s passionate about their aesthetics, snapping photos of the detectors when the light hits just so.

“Maybe it’s pretentious, but it is a work of art. It is feeling so powerful, in a sense, because it came all from your hands. I do feel sometime like a Michelangelo,” she said.

Her less romantic, less Italian colleagues compare the detectors’ profile to other shiny objects, like a robot, or a spaceship, or, most unfortunately, a trash can.

Aprile’s concern with the device’s design may have to do with the fact that its functionality is not a given.

Since scientists don’t know what dark matter looks like, they can only guess at the best way to see it.

“Unfortunately, in this business we don’t really know we are following the right path,” she said. “Sometimes I get depressed, but there’s no time to get depressed now. I don’t think I will ever give up. Because there is no other way.”