Pakistani scholars concerned that Urdu script being lost to technology

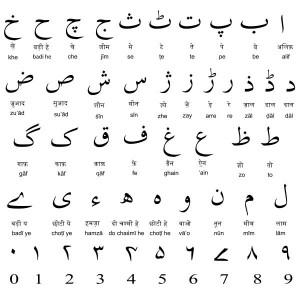

Urdu Alphabet with Devanagari and Latin transliterations. (Photo by Goldsztajn via Wikimedia Commons.)

Cell phone users in Pakistan sent an average of 128 text messages each per month in 2009, government figures show.

That was the fifth highest figure among all countries in the world. Fueled by texting, a growing number of Pakistanis are using Latin letters to write Urdu, the national language, instead of using the official Urdu script.

Though the trend is limited, it has left some Urdu purists concerned about what happens if the trend continues.

While it may sound harmless, it has unintended consequences. Because the first generations of mobile phones couldn’t send text messages using Urdu script, Pakistanis improvised and started converting Urdu phrases into the Latin alphabet. Even though Urdu-capable phones are more common now, many people have become used to the Latin script.

Shaista Parween, a math and computer studies teacher, said texting-mad students are just as comfortable writing Urdu in Latin as they are using the regular script. In fact, she said they sometimes do schoolwork using the Latin alphabet.

“I’m facing this a lot in my classes,” Parween said. “Latin Urdu is being used so much, what can we do? We can’t say it’s wrong if they are trying. It’s used so much in the media and television, that’s why.”

Officially Urdu is written in a variation of the Arabic script. But while the use of Latin letters for Urdu has reached high levels, though still a minority, it isn’t the first time it’s been done.

European missionaries and administrators converted Urdu into the Latin script in the 18th century. And in the 1950s, military ruler Ayub Khan proposed officially writing Urdu in Latin letters, just as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had done with Turkish decades earlier. But religious leaders said the Arabic script was an important connection to Pakistan’s Islamic identity, so Ayub abandoned the idea.

But now, tech-savvy kids are doing what a military dictator couldn’t achieve 40-years ago. And many Pakistanis aren’t happy about it.

“Trying to write a language in another script is like trying to drop off your skin and trying to have a new one,” said Rauf Parekh, an assistant professor at the University of Karachi’s Urdu Department.

He’s concerned about the impact this will make on society if people stop learning the Urdu script.

“They will be cut off from their culture, from their tradition, their history, their classical literature. How are they going to enjoy if they cannot read it in the original. So it’s a kind of deprivation on cultural and educational side. They won’t feel it perhaps now, but maybe hundred years from now they will realize what a great loss they have incurred,” he said.

While Parekh bemoans the loss of traditional Pakistani culture, a new kind of “text messaging culture” is emerging. Pakistanis use text messages for just about anything, but especially for passing on political jokes, poetry, quotes and for flirting.

Karachi’s main marketplace for printed books — the Urdu Bazaar — has hundreds of small book vendors. Many sell booklets of bite-sized poems and jokes compiled specifically for sending as text messages.

One book is titled “Cool SMS,” another “Love & Love SMS.” Each joke or poem is printed in both the Urdu script and the Latin transliteration.

“It’s been about 10 years that these books have been published now,” shop owner Basharat explained. “There was a lot of demand for them initially. This is because the majority of our population is not educated, so Latin Urdu books were made so that every person can read the books and send SMSs. It made it so much easier.”

Nowadays, Basharat said, the SMS booklets don’t sell as much, in part because cell phone companies have caught on and are sending Latin-Urdu text messages themselves.