New Tennessee law: encouraging creationism or academic freedom?

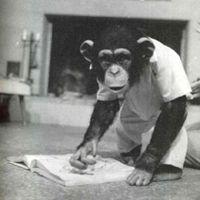

A new bill in Tennessee is being called the “monkey bill,” a reference to the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925. (Photo courtesy of Science and Behavior Books, Inc.)

Tennessee has been a battle ground state for supporters and detractors of evolution.

In the past century, laws in favor of teaching evolution in Tennessee public school classrooms have been passed, repealed and re-established many times. The famous Scopes case, or “Monkey Trial” as it was called, was held in 1925 in Dayton, Tenn. The case pitted leaders in the Christian community against the ACLU and local science teacher John Scopes, who was against a bill banning the teaching of evolution in the classroom.

Fast forward to 2012, and the same ideas continue to be hashed out in Tennessee courtrooms. The newest rendition of the “monkey bill” House Bill 368, also known as the Tennessee “academic freedom” law gives teachers permission to, proponents say, encourage critical thinking around scientific theories.

The bill says “teachers shall be permitted to help students understand, analyze, critique, and review in an objective manner the scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses of existing scientific theories covered in the course being taught.”

Josh Rosenau, the programs and policy director at the National Center for Science Education, a non-profit that defends the teaching of evolution and climate science in public schools, doesn’t think the bill is intended to promote critical thinking.

“Encouraging critical thinking is great,” Rosenau said. “The problem is when you apply that critical thinking to the way this bill is written, all anyone seems to want to talk about is pitching evolution against creationism. That’s not something for the science class, that might be something for a comparative religions class.”

Rosenau thinks the new bill undermines sound science.

“Scientifically speaking, evolution is just not controversial,” Rosenau said. “To talk about the strengths and weaknesses of it assumes that there are legitimate scientific weaknesses that are appropriate for a high school science classes. And there just aren’t.”

Nelson Turner, a teacher at The Woodland Middle School in Brentwood, Tenn., has taught seventh grade science for 15 years. Nelson thinks there are some problems in the evolution theory, and those problems should be explored in the classroom.

“What the debate comes down to is your understanding of what education really is. If there really are two sides to an issue and you’re only teaching one view point, then I don’t call that education, I’d call it indoctrination,” Nelson said.

Nelson said the new bill is not well-understood. He said it doesn’t support teaching creationism.

“That’s not what the Tennessee law is,” Nelson said. “Some people think this is an open door for us to teach creationism, but actually the law has an amendment to it that allows discussion of controversial issues only for topics that are related to our curriculum.”

Rosenau is skeptical that discussing scientific topics in school curriculums will encourage learning.

“In seventh grade or ninth grade, students are still learning what science is and what science isn’t. One of the things that worries me about bills like this one is that it blurs those lines,” Rosenau said. “It makes it harder for students to learn where we draw that line and how science over centuries has developed a set of systems for testing things about the world that makes it an incredibly powerful tool and makes it different from religion. Not to say that for all questions it has to be superior, but in science class we should teach science and not muddy the waters.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?