Greek antiquities at risk as budgets shrink, economy falters

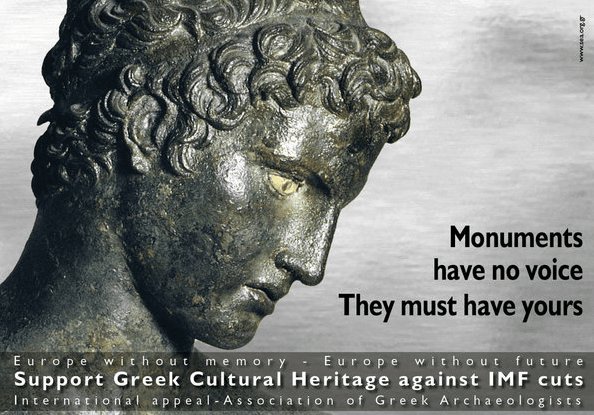

The International Association of Greek Archaeologists Wednesday unveiled a campaign to try to rally support around preserving Greece’s ancient artifacts — despite tough budgets. (Poster courtesy of the Association of Greek Archaeologists.)

Monuments have no voice. They have us.

That was the message from the Association of Greek Archaeologists at a news conference in Athens Wednesday.

Despoina Koutsoumba, head of the association, said the Greek government is failing to protect Greece’s cultural heritage, leaving the country’s antiquities up for grabs.

“We don’t sell our cultural heritage, our history or our dignity,” Koutsoumba said. “These are things that are not for sale.”

Greece’s economic woes have forced the country to adopt tough austerity measures, resulting in severe budget cuts.

Last week, staff at Greece’s culture ministry took to the streets in front of the National Archaeological Museum. They warned that the austerity programs were hurting their work.

Maria Tzagkarak, sitting at a museum cafe that same day, recalled that she'd recently lost her job as a museum guard. She said she and her friends, also former guards, come here regularly to press for 10 months of back pay.

“They are unpaid for months, and that is a great problem,” Tzagkaraki said. “I’m waiting for more thieves in the museums, but they don’t care.”

One group that said it does care about the theft of Greece’s heritage is the Police Antiquities Squad. Dimos Kouzilos, a deputy director, worked narcotics for 17 years before joining the squad. He said he fell in love with the work immediately.

Kouzilos said Greece’s troubles are definitely causing an increase in lootings and robberies.

“The economic crisis is driving more people to commit crimes,” he said.

Just last month, masked men with guns took dozens of items from the museum at ancient Olympia. There was also a theft of a painting from Greece’s National Gallery of Art.

Kouzilos said both incidents are “open wounds.”

“But I swear to you,” he said, “both cases will be solved.”

Jack Davis, director of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, said Greece is a place where you can find an antiquity on every corner.

“They’re everywhere,” he said.

When you walk through the agora, the ancient Greek market, you start to realize how hard it is to safeguard Greece’s antiquities. The agora is one of more than 1,000 officially listed archaeological sites spread out across all of mainland Greece and myriad islands.

Davis said small-scale looting and black-market trading has always been a problem in Greece. But in recent years it’s gotten worse.

“There are gangs operating throughout the Mediterranean, criminal gangs who systematically loot archaeological sites and smuggle finds outside the borders,” Davis said.

The collectors who are driving the demand these days are mostly from the Far East and Middle East, and they have no interest in putting the works in museums, Davis said.

“I can’t document this, but we know that there are significant private collections that are maintained secretly, never put on display and only shown to a privileged few friends," he said. "So you never become aware that particular individuals have these particular materials.”

Whenever an antiquity disappears from Greece, something more than the object is lost, said Nikolas Zirganos, an investigative journalist who’s written extensively on the illegal trade in antiquities.

“We lose very valuable information, because we don’t know this masterpiece. We can’t study the scene, we can’t study in a proper way the society that created this masterpiece," he said.

Zirganos praised the work of the Greek antiquities squad. But he said more needs to be done to go after the collectors who are driving the demand.

Kouzilos agreed but admitted his own department is feeling the economic pinch right now.

There have been a lot of cuts, Kouzilos said, even to wages.

“We will pay our own expenses, if necessary, to track these people down," he said. “That’s how it must be done in these circumstances.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?