Disputed art disappears from University of Wyoming campus

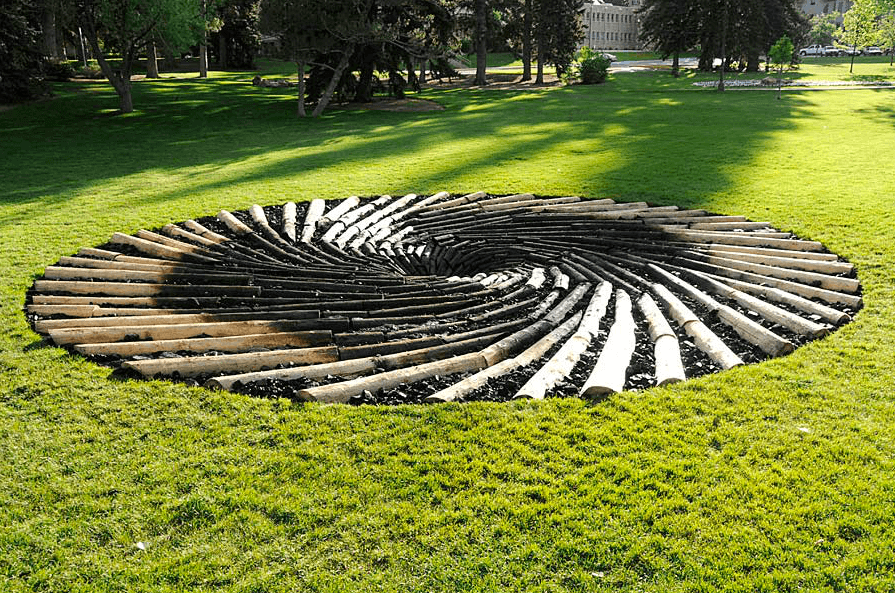

British artist Chris Drury’s “Carbon Sink” sculpture was on the University of Wyoming’s campus for less than a year. (Photo courtesy of Chris Drury.)

It’s easy to overlook public art — until it suddenly disappears.

Penn State removed its statue of the late football coach Joe Paterno last month after a huge outcry both for and against keeping it. Last year, Maine’s governor made the controversial decision to remove a mural that celebrated the labor movement that was housed at the state’s Department of Labor.

A year ago, the University of Wyoming Art Museum commissioned an outdoor sculpture from British artist Chris Drury. “Carbon Sink” was a 36-foot-diameter vortex of logs killed by pine beetles atop a bed of Wyoming coal.

Drury said he wanted to draw a connection between Wyoming’s extractive industries and the damage wrought by climate change, which experts said had created a devastating pine beetle infestation across the West.

After this year’s commencement — less than a year later — the sculpture was gone. The logs put in a scrap heap, and the coal thrown into the university’s power plant.

“I thought it was a little hypocritical to use carbon dollars to fund an anti-carbon sculpture,” said Tom Lubnau, the Republican majority leader of the Wyoming House of Representatives.

Lubnau represents the City of Gillette, the center of the Wyoming’s coal and natural gas region. He notes that between 60 to 80 percent of the state’s budget — and by extension, the university’s budget — comes from taxes on the energy sector.

Lubnau’s comment got play in the New York Times and elsewhere, something he said was “surprising,” since in his mind, he was just pointing out the obvious. He denied that lawmakers demanded the removal of the sculpture.

“It was always meant to be temporary,” Lubnau said.

But Jeffrey Lockwood, a University of Wyoming professor who has written about the controversy, said the statue’s removal “was a political response to political pressure.” “Carbon Sink” was intended to remain in place until it had eroded entirely.

In a recent bill, the Wyoming legislature gave the university’s energy resources council, an industry group, right of approval over art going up in the the newly renovated recreation center. Lubnau said he didn’t see a problem with that.

“What’s wrong with allowing … (the) industry (to) have approval, or the veto power on a few pieces of art in this one building?” he asked.

Lockwood sees the opposition to the work as ironic. He said the sculpture was not meant as an attack on the energy sector. Producers and consumers alike, he says, are “all culpable with regard to climate change.”