History of Iraq part II: the rise of Saddam Hussein

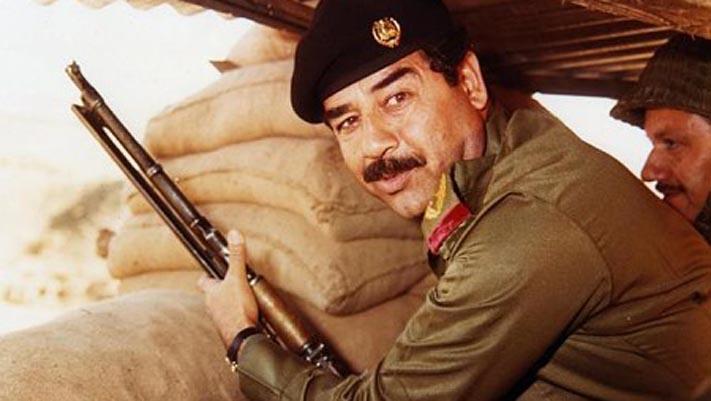

Saddam Hussein Iran-Iraq war 1980s.

Twelve years ago, as allied aircraft began bombing Baghdad at the start of the Gulf War, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein gave a telling speech.

Here's an excerpt: "Bush, the Satan, has perpetrated his crime and the great battle has been initiated. The Mother of all Battles between the triumphant truth, with the support of God, and the evil push by Satan, which will be beaten eventually, God willing."

Hussein made the perfect enemy. He had invaded a sovereign country. Now, he refused to back down. Faced with war, he was defiant, belligerent, and unrepentant.

He still is.

"He is a bigtime and compulsive gambler," says Israeli historian Amatzia Baram, who has spent a career studying Saddam Hussein.

"Like all compulsive gamblers he thinks that maybe he lost last time, but he's going to gain everything back this time and even more. And so far he always lost," Baram says.

Hussein was born into a poor family in 1937 in the town of Tikrit north of Baghdad. His father died before he was born. When he was still an infant his mother left him with relatives and returned to her home village outside Tikrit. She didn't send for him until she remarried a couple of years later. Life in the village was rough. His new stepfather was not kind. And the neighborhood kids taunted the young Saddam, according to Baram.

"Sometimes children used to call him ibn harram which means bastard. That of course was not correct. He was not such. But he had no defender. He had to fend for himself. And he became to rely only upon himself. That created a person who on the one hand was very independent. On the other hand it created a child who trusted no one, who found it difficult to love people, who had a grudge against his society, against his village, against his hometown, against people," Baram says.

Saddam Hussein became a loner and a bully. He didn't last long in the village. By the age of 12 he had joined his uncle in Tikrit so he could go to school and learn to read. His uncle was a teacher, with an interesting past, according to Phebe Marr, author of "The Modern History of Iraq."

"His uncle had been an army officer who had been not only thrown out of the army, but put in prison because of an anti-British coup in 1941. And frankly he had no truck for British or foreign influence. It was part of the nationalist trend at the time. And he certainly instilled this anti-colonial sentiment in Saddam when he was raised in that household," she says.

The other thing that was drummed into Hussein in Tikrit was the importance of family ties.

"Tikrit in those days was tribally organized. Tribal values, tribal clan life was really at the core of how, not only how you organized yourself but how you identified. This is what Saddam comes out of and he brought a lot of that with him to power and to government organization today," Marr says.

By the early 1950s, a teenaged Hussein was demonstrating against the government. Like countless other Iraqis, he was expressing a general sense of resentment against British colonial rule and Iraq's domination by rich landowners. Pan-Arabism was also on the rise – the movement to bring Arab states together into one big nation. In 1958, a revolution overthrew Iraq's British-backed monarchy. The change ushered in a chaotic and violent decade. By this time, Saddam Hussein had joined the pan-Arabist Baath Party. In 1959 he and fellow Baathists tried to assassinate Iraq's new military leader General Abdel Karim Kassem. The attempt failed, and Saddam Hussein was forced to flee the country. Four years later he came back, just after the Baathists did manage to kill Kassem.

They showed their ruthless side, parading the general's bullet-riddled body on television. But the Baathists were thrown out of power nine months later. The years after this, the mid-60s, were critical ones for Hussein. He linked up with his one of his uncle's cousins, now high up in the Baath Party.

Historian Charles Tripp says Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr and his young sidekick made quite a team.

"Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr was very much an old style regimental officer. And Saddam Hussein was not an officer, was not in the army, but was an excellent "street organizer" I think is the phrase often used euphemistically which meant someone who could organize the beating up of opponents, demonstrations, street violence, who had his ear to the ground in ways that Ahmad Hasan al Bakr couldn't," Tripp says.

The Baath Party returned to power for good in 1968. Bakr became president and Hussein quickly emerged as his right-hand man. And he turned out to be more than just a party thug. He was also methodical, and politically astute. He took over the state security apparatus. Then he and Bakr began to eliminate their rivals. Some were executed, some were shipped off to diplomatic posts, some were simply outmanoeuvered. Even as they consolidated their power, the Baathist leaders were intent on modernizing their country. And shaking off foreign influence.

President Bakr announced the nationalization of the Iraqi oil industry in 1972:

"…Patriots and progressives, in the Arab homeland and in the entire world, in waging decisive battle against the oil monopolies our revolution is taking forward positions in face-to-face clashes with imperialism and its monopolies, to carry out an honorable patriotic and national duty…"

His message was "Arab oil for the Arabs." A year later, fuel prices shot up. Iraq's oil revenues quadrupled. The Baathist regime poured its new money into the military, but also into education and infrastructure. Roads were built, villages electrified, literacy campaigns launched. Iraq became a modern, urban state with a substantial middle class.

But if Iraq was modernizing on the surface, behind the scenes something far more primitive was unfolding.

Hussein turned out to be merciless in his quest for power. In 1979, he made his move on his old patron, Bakr. Hussein forced his relative to resign and took over the presidency himself. No sooner had he done so than he purged the party's Revolutionary Command Council. Hussein announced the discovery of a plot against himself and the Baathist regime. Then he held a kind of show trial, which he videotaped. The footage shows party members gathered in a large auditorium. Hussein is on stage, smoking a cigar. The alleged plot leader confesses his crime. Then he reads out the names of his supposed co-conspirators. As their names are called out they are led from the hall to be arrested and shot. Members of the audience shout out their allegiance to Saddam Hussein.

"You notice the mounting hysteria as nobody knows quite who's name is going to be called out next," says Charles Tripp. " And so of course this means that the survivors cheer even more frenziedly for Saddam Hussein. It's a very chilling documentary. But Saddam Hussein wanted that to be seen. This was an exercise of power which he would use to impress upon the surviving Baathists in Iraq that he had absolute control over their lives and deaths."

"The whole thing is like theatre except it happens to be real," says Kanan Makiya, a prominent Iraqi writer and dissident. He has also seen the footage and researched what happened next.

"And when the firing squad is assembled to execute these so-called traitors, who does he use but the remaining members of the Revolutionary Command Council and his own ministers and so on, to implicate them, in a sense, in his own rise to power. Because that is the event upon which he cements his own presidency," Makiya says.

By this point, any political ideology Saddam Hussein once adhered to seemed to have vanished. Fear became the key to his rule.

Phebe Marr says Pan-Arabism had given way to Saddamism.

"This is a one-man regime, it's more of a personal dictatorship in which we find the cult of Saddam. And yes it's in the name of the Baath Party, and yes there's some kind of ideology, but the ideology is whatever Saddam says it is," she says.

And what Saddam has said over the years has been revealing.

Amatzia Baram has combed through his speeches and official pronouncements and says the Iraqi leader's beliefs are infused with megalomania. Hussein wants to be the leader of the Arab world and sees himself as a latter-day version of various historical figures – including the Islamic warrior Saladin, also born in Tikrit, and the ancient Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, conqueror of the Jews.

"That explains why he built those huge palaces, and absolutely fantastic palaces, very expensive, people need the money more for other purposes, but never mind. He sees himself as a great builder and a great conqueror," Baram says.

In 1980, Saddam Hussein invaded his neighbor, Iran. There were old tensions between Iran and Iraq, including a territorial dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway that separates them. And there was fear on the Iraqi side that the Iranian revolution might jump the border. But mostly Hussein wanted to show his prowess.

Charles Tripp says it was a massive miscalculation.

"It's almost certain that he thought it would be quite a short, almost symbolic, war. He would seize some kilometers of territory. The Iranian government would sue for peace, and they would haggle, and eventually the Iranian government would give back the bit of the Shatt al-Arab that Iraq had ceded to it in the mid-1970s, but more importantly for Saddam Hussein's prestige, acknowledge his power," he says.

Instead Iraq found itself in a war for its survival that dragged on for 8 years and killed more than a million people. Even as that war ground on, Hussein pushed ahead with another military project: weapons of mass destruction. Israel was especially alarmed by a new Iraqi nuclear reactor. In 1981 Israeli warplanes bombed the plant into oblivion, fearful Hussein would use it to make plutonium for weapons.

And Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin believed Iraq would attack Israel after it finished with Iran.

"On the 4th of October in Baghdad in the newspaper al Tahawra the following statement was made: the Iranian people should not fear the Iraqi nuclear reactor which is not intended to be used against Iran but against a Zionist enemy," Begin said.

Israel's strike stymied Hussein's nuclear ambitions, but he pressed ahead with chemical weapons. Iraqi aircraft began dropping mustard gas on Iranian troops in 1983. Later Hussein would turn chemical weapons on his own citizens, Kurds in the north of Iraq. The Iran-Iraq war finally ended in 1988. It had been devastating to both countries. Hussein had started the war flush with cash and at the pinnacle of his powers. He ended it with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis dead, and billions of dollars in foreign debt.

It was a dangerous moment for him, says Tripp.

"There were coup attempts, there were mutinies, there were murders. There was a great deal of unrest. And I think beyond that the general feeling amongst the Iraqi public that we've survived the war and now we deserve something else. But he also faced a problem in his own family, in his own clan. He found that there were ambitious members of that family who were wanting to replace Saddam Hussein," he says.

The Iraqi leader appealed to his Arab neighbors for help. He wanted them to write off his war debts. Then he started haranguing them. Saddam Hussein accused next-door Kuwait of stealing Iraqi oil. He demanded compensation. Then, on August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded.

Saddam Hussein's spokesman announced the annexation of Kuwait on Baghdad television. "Our fellow citizens," he said. "History has proved that Kuwait is a part of Iraq. We are appealing to all Iraqis to go with their heroic leader, Saddam Hussein."

Hussein's gamble backfired. The West had supported him against Iran in the 1980s. But now it turned against him. The stability of the Persian Gulf was too important.

Phebe Marr says the Iraqi leader simply didn't understand the rest of the world and was surrounded by people who told him only what he wanted to hear.

"If you look at this man and this regime–he has kept himself in power through this clan network, not exactly egalitarian, not exactly modern. And the more power that has come into his hands, the worse the decisions have gotten. It is not a mystery," Marr says.

Early in 1991, a US-led military coalition forced Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait. In the days after the Gulf War, the Iraqi people found themselves at a juncture.

The regime was faltering, according to Kanan Makiya.

"There is a wonderful Iraqi colloquial expression about what happened in 1991. In Arabic it is hajiz al-khawf inkiser, or "the barrier of fear broke." And fear in that sense truly was like a wall, like the Berlin Wall that broke in 1991 that led to the uprising in which the overwhelming number of people participated in trying to overthrow the regime," he says.

But Hussein's forces managed to crush the uprising. The international coalition that had just driven him out of Kuwait stood by and watched. The familiar repression returned. 12 years later, Saddam Hussein remains the president of Iraq. Since the Gulf War, he has withstood sanctions, weapons inspections and airstrikes. The Iraqi dictator may have lost his wars outside Iraq, but he has never yet lost his hold on power at home.