Professors fear creeping authoritarianism in academia amid Harvard fallout

Professors who supported embattled Harvard President Claudine Gay said they felt surprised, stunned and speechless when she resigned. As the dust settles, they’re warning that Gay’s resignation signals a dangerous intrusion of partisan politics into American higher education, at a time when democratic freedoms are declining globally at home and abroad.

Harvard political science professor Ryan Enos said barbed political threats — like US Rep. Elise Stefanik’s warning that political leaders would “expose the rot in our most ‘prestigious’ higher education institutions” — are more than just rhetoric.

“When we let that spill into an attack on our higher education system, then really, what we’re doing is potentially damaging something that is one of America’s great assets,” Enos said. “It can play into these authoritarian impulses and we should all resist, regardless of our politics.”

Higher education institutions — especially top universities like Harvard — have long sat in the crosshairs of conservative politicians and right-wing activists, as well as many Americans who generally dislike the elitism they embody. But some academics warn of a new, dangerous lurch toward authoritarianism in the congressional proceedings that led to the ouster of two Ivy League presidents.

Gay’s resignation followed months of criticism about her responses to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel, her legalistic congressional testimony on claims of antisemitism in December and allegations of plagiarism in her scholarly work by conservative activists.

Even Gay warned of the broader implications of the campaign against her in a New York Times op-ed.

“This was merely a single skirmish in a broader war to unravel public faith in pillars of American society,” she wrote.

Enos said Harvard’s governing board caved into pressure from “a virtual mob” of right-wing activists who also took credit for Gay’s resignation and vowed to continue investigating antisemitism in higher education. He and other professors viewed the move as part of a larger authoritarian effort — a political playbook.

“It fits a pattern that we see in other countries where authoritarian leaders have attacked higher education,” he said.

Lessons from abroad

Jessica Pisano, a New School politics professor who wrote the book “Staging Democracy: Political Performance in Ukraine, Russia and Beyond,” agreed.

“It starts with attacks on strong institutions in order to intimidate everybody else,” said Pisano, who studies higher education in Eastern European countries like Hungary and Russia where civil liberties are declining.

Pisano said American college leaders would be wise to learn from the experiences of academics in Ukraine, who are fighting for their lives in a war with Russia where the Kremlin is bombing schools and where the previous authoritarian government had increased political bureaucratic control over education.

“It’s a very boilerplate kind of playbook,” Pisano said in an interview from Ukraine, spelling out how it works: Bury universities in constantly changing paperwork, blackmail opponents and gut research institutions.

The nonprofit pro-democracy advocacy group Freedom House has tallied 17 consecutive years of declines in democracy worldwide. It noted, in Afghanistan, a substantial rollback in academic freedoms under the Taliban: Women are not able to attend universities and educational materials are censored.

In Hungary, Pisano said, censorship is another tool. The government crackdown there began with anti-democratic policies like, “Don’t say ‘poverty’ in the classroom,” which Pisano compared to Florida’s 2022 “Don’t Say Gay” bill. Then it expanded to include shutting down entire universities. The authoritarian regime in Hungary forced Central European University in Budapest to decamp to Vienna.

“Their strategic objective is societal discord and polarization,” she said. “Making us fight with each other — making Americans fight with one another — so that, at the global, level no one will be minding the store, that’s their whole game.”

To avoid that game, Pisano suggested, Ukrainian academics have something to teach their American counterparts.

“They’ve been able to unite a really diverse society that was as polarized as the United States is by saying, ‘Look, we’re under attack. There are some shared values and standards most of us can agree on, so let’s focus on those,’ rather than getting drawn onto a battlefield to discuss things that are only going to deepen our divisions,” she said. “We can choose not to get drawn into wedge issue battles. It doesn’t mean we don’t act.”

Echoes of McCarthyism

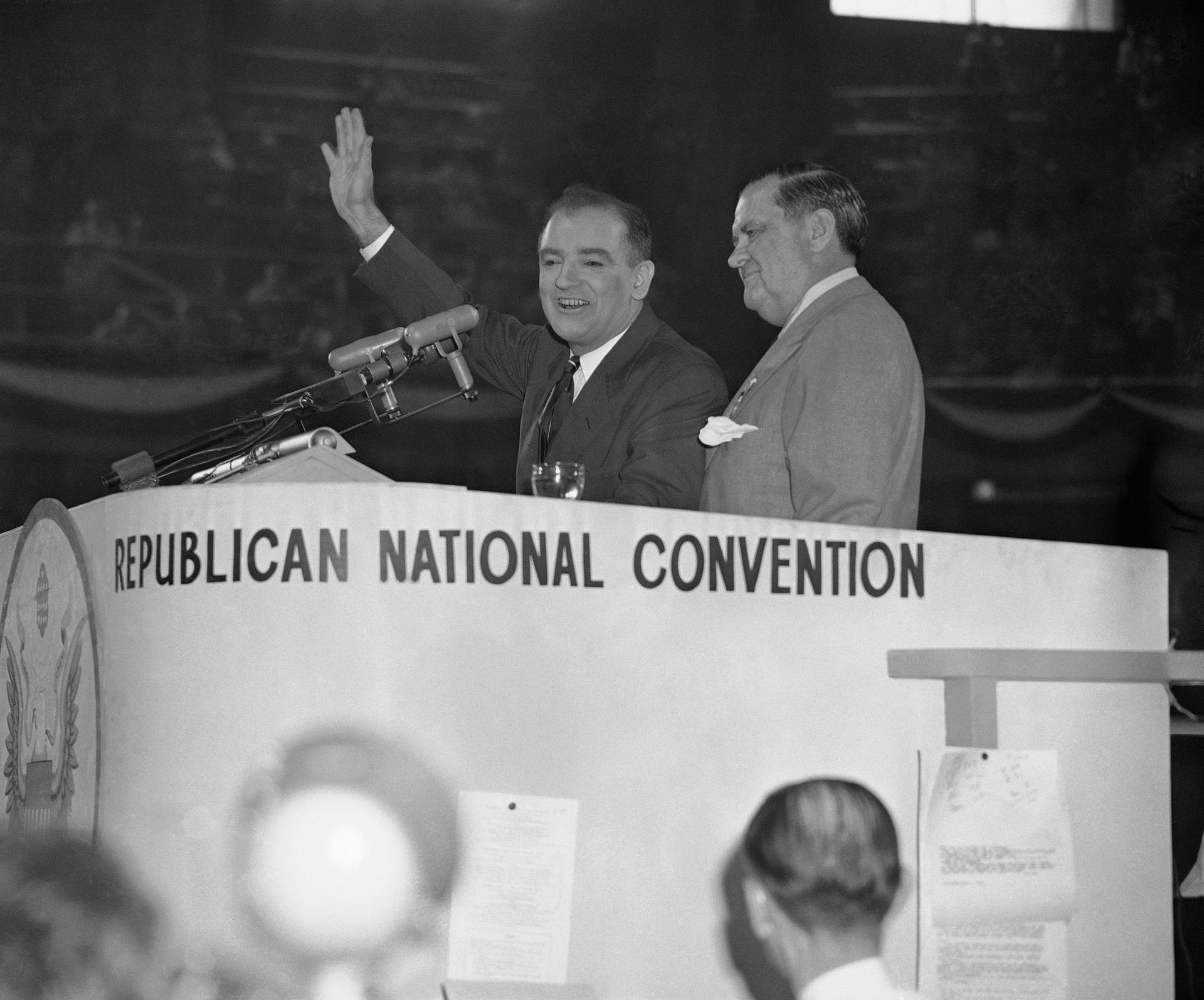

Harvard’s Enos compared recent congressional inquiries into academia — and the “virtual mob” that crusaded for Gay’s ouster on social media — to Joseph McCarthy’s attacks on universities back in the 1950s.

Speaking at the 1952 Republican National Convention, McCarthy whipped up a frenzy around the notion that the Soviet Union had infiltrated institutions like Harvard.

“One communist on the faculty of one university is one communist too many,” McCarthy shouted over roaring applause inside the International Amphitheater in Chicago.

Enos said the public’s fears of communism did not come from nowhere.

“It was drawing on something that, in many ways, was a legitimate fear that people were dealing with because of the Cold War,” he said. “And it’s the same thing now, where people in the House of Representatives are drawing on a real concern about antisemitism to turn it into this expansive attack on universities.

“People like Elise Stefanik are not trying to make Harvard a better place,” he added. “They’re just trying to make it more in their mold.”

But even some who also see a rising tide of authoritarianism globally disagree that it was the primary reason for Gay’s departure.

Civil liberties lawyer Harvey Silverglate, the Harvard-educated co-founder of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), said dire warnings of authoritarianism are opportunistic.

Silverglate, a self-described “libertarian liberal,” said Gay’s supporters are ignoring her managerial missteps and trying to make her downfall about race and gender or rising authoritarianism.

“She has the chutzpah to blame her problems, in part, on her being a Black woman,” Silverglate said. “If the Harvard Corporation wanted a Black woman as president, they should have searched the landscape, since there are many fabulously competent Black academics around.”

Gay did not respond to a request for comment. Harvard declined several requests for interviews.

But to others, Gay’s race was a clear factor in her treatment. Jasmine Harris, a sociologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio and author of “Black Women, Ivory Tower: Revealing the Lies of White Supremacy in American Education,” said Gay was held to more rigid standards than a white man or woman in the same role.

“Harvard is founded on whiteness,” Harris said. “Accusations of plagiarism don’t speak to her lack of fitness for the job, but instead highlight how easily her decades of professional achievement could be undermined by those with a vested interest in doing so.”

How should universities respond to threats?

Some critics want colleges to stop commenting publicly on controversial social and political matters entirely.

“The best approach for colleges and universities moving forward is to adopt a position of institutional neutrality,” said Nico Perrino, an executive at FIRE. “Be the forum for those discussions rather than a protagonist in the story.”

Institutional neutrality appears to be under consideration at Harvard as it searches for its next president. Such a stance has already been adopted by more than 70 colleges and universities, including Princeton, Purdue and Georgetown, according to FIRE. Progressive faculty members who had previously opposed it because they wanted their institutions to take moral and political stands are increasingly willing to consider it.

“Broad-based support for institutional neutrality seems higher now than it has ever been during my time at Harvard,” said Alison Frank Johnson, a professor of history and Gay supporter.

News reports have suggested Gay considered sending a neutrality plan to Harvard administrators in the days before she resigned.

Others said it’s not an effective way to respond to political attacks from the right. Lynn Pasquerella, former president of Mount Holyoke College and current president of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, said remaining neutral on social and political issues like the war in Gaza isn’t an option.

“We need to get beyond what I call ‘the rules of the tweedy past’ where the expectation is that presidents are going to be thought leaders who publish in scholarly journals but don’t do much else,” she said.

Pasquerella said college leaders need to be involved in fostering change, whether in their local communities or in front of a congressional subcommittee. That means stepping off campus and engaging in “public intellectualism” and the cultural debates of the day.

“It’s a frightening time,” Pasquerella said of the political threats to academia. “This poses a genuine existential threat to higher education as it was imagined, and the democratic purposes of higher education.”

While many view it as merely political theater on an international stage, she said, it needs to be taken very seriously.

An earlier version of this story appeared on GBH.