At a pro-government rally in Caracas, supporters of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro played trumpets and beat on drums.

They carried banners with images of famous socialist leaders like former president Hugo Chavez and Che Guevara, the revolutionary fighter from the 1960s.

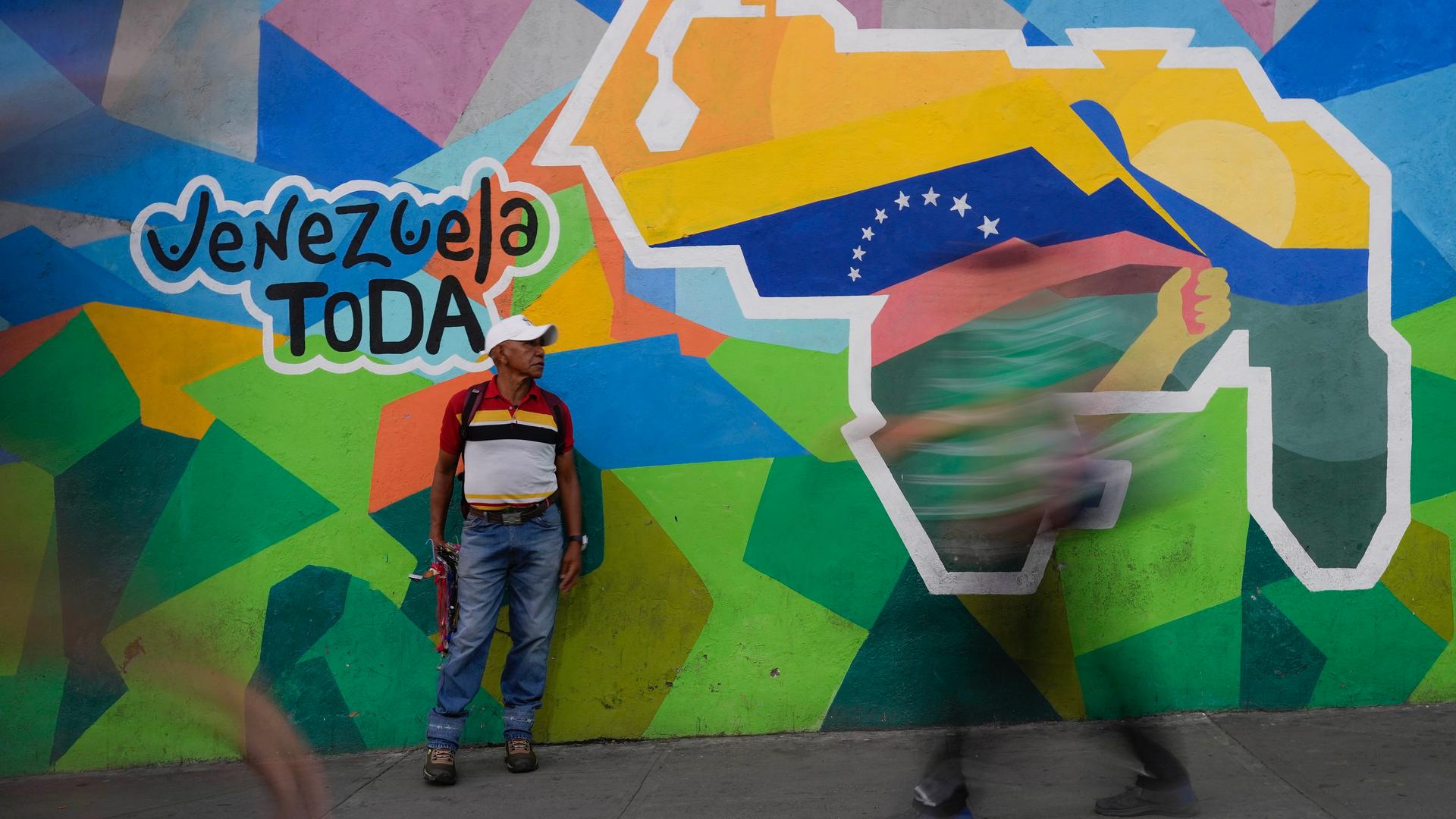

But many also used shirts with a different kind of symbol — a new map of Venezuela that includes a large strip of land known as the Essequibo region.

“This is our territory,” said Jose Olivar, one of the government supporters at the Jan. 23 rally. “It’s rich in resources, and that’s why they want to take it away from us.”

The Essequibo is about the size of Florida. And it’s located 600 miles to the east of Venezuela’s capital.

Recently, Venezuela threatened to annex the oil-rich territory, which has been governed by neighboring Guyana since 1966, and was previously part of the colony of British Guyana.

As Venezuela prepares to hold presidential elections in the year’s first half, some expect the border dispute to intensify.

“Maduro is very unpopular right now, and according to some polls, his approval rating goes from 12 to 15%,” said Tony Frangie Mawad, the editor of Caracas Chronicles, a website dedicated to Venezuelan politics.

“The mechanisms he used previously to win elections have imploded … and that implies new strategies and plans for 2024.”

Venezuela has long claimed the Essequibo, arguing that the sparsely populated territory was part of Venezuela as a Spanish colony. It was also included in Venezuela’s constitution when founded in 1811.

The dispute has been mostly limited to courts and diplomatic forums, but Venezuela’s government has become much more vocal about it over the past two months.

In December, the country organized a referendum in which voters said the Essequibo should become a new Venezuelan state.

In January, the government organized a nationally televised funeral for Domingo Sifontes, a general who died in 1912 and had played a small part in the Essequibo controversy. Back in1895, Sifontes had ordered the arrest of a group of British officers who were exploring the Essequibo region and taken over an abandoned Venezuelan fort. During the funeral service, soldiers dressed in 19th-century uniforms carried Sifontes’ exhumed bones into a chapel where national heroes are buried, and Maduro presided over the ceremony.

“Sooner or later, the Esequibo will be ours forever,” Maduro said in a 40-minute speech, describing Sifontes as an example for Venezuelan youth to follow. “Long live the great country of Venezuela and its national heroes.”

This kind of rhetoric has led to speculation that Venezuela is preparing to take over the Essequibo — though others have said that it’s just political theater.

Tony Frangie Mawad from Caracas Chronicles said the Venezuelan government is trying to find ways to prepare for this year’s presidential election and used the referendum on the Essequibo to “measure its capability to mobilize voters.”

Mawad said a full-scale invasion of the Essequibo would be very costly for Venezuela.

“I honestly don’t think there will be a war with Guyana. Venezuela hasn’t been involved in a war with another country in centuries,” he said.

But Guyana’s government is taking no chances.

Guyanese leaders met with defense officials from the United States and Britain in December to discuss the threat from Venezuela. Guyana’s small navy also conducted military exercises with a British patrol ship, prompting Venezuela to conduct its own military exercises in the eastern Caribbean.

“We see Essequibo not as some disputed territory that belongs to no one,” said Orin Gordon, a Guyanese columnist and political analyst. “But intrinsically as a part of Guyana.”

While the disputed territory lacks big cities and has few roads, it is home to vast tracts of rainforest and spectacular geographic features like the Kaieteur Falls. Its shores on the Atlantic Ocean are rich in oil reserves that Guyana started to exploit in 2016. Gordon said that losing the Essequibo, which makes up two-thirds of Guyana’s land area, would be “catastrophic.”

“I think that an occupation of a small part of Guyana is possible,” Gordon said. “Venezuela knows full well that Guyana [has a] very weak military, and if it decides to take a bite out of Guyana, there’s very little Guyana can do.”

Guyana wants the dispute settled at the International Court of Justice, which has told both countries to present their written arguments to the court in April. However, Venezuela’s government has insisted on solving the dispute through direct talks with the Guyanese government.

Rafael Badell, a Venezuelan lawyer who has written a book about the Essequibo dispute, said that was a mistake.

Like many Venezuelans, Badell believes his country was cheated by an arbitration tribunal in Paris that awarded most of the Essequibo to the United Kingdom in 1899. He said Venezuela has a good chance of proving to the court that the Paris ruling should be overturned.

“Venezuela has key documents that show that in 1814, the British only acquired a small portion of the land that now makes up Guyana,” he said. “But those documents were not considered in the Paris ruling.”

An annulment of the Paris ruling would open new possibilities that could include talks between both sides or an effort by the court to redraw the land border between both nations, as well as a maritime border that is also under dispute.

“Venezuela may not get all of that territory,” Badell said. “But it is clear that it has rights over some of the land that Guyana is currently occupying … especially the territorial waters.”

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!