While most of London is preparing for bed, Dr. Qian Xu clocks in for her graveyard shift inside a bustling emergency room in southwest London.

Paramedics shuffle in patients on gurneys. One man dislocated his shoulder, and another just lost a pint of blood after accidentally puncturing a vein. Meanwhile, there’s a waiting room full of dozens of people.

When she started her medical career over a decade ago, Xu said the average wait time was just over two hours. These days, “people don’t bat an eyelid at four hours,” she confessed. “It’s more like approaching 12 hours. We need to do something.”

Xu said the ER, referred to as A&E in the UK, has become the first point of contact for many patients, who, since the pandemic, have put off routine doctor’s visits until it’s too late. There, it’s a struggle to sort them out, she said.

Her emergency room is hardly an outlier when it comes to being spread too thin. Britain’s National Health Service, known as the NHS, celebrated its milestone 75th birthday last month.

The NHS is treasured for its motto, which promises Britons health care “free at the point of delivery.” But a series of recent crises have concerned many health care providers about the public institution’s ability to continue delivering on that promise. Plagued by staffing shortages, crumbling equipment and infrastructure, and an aging, sick population, the NHS is facing perhaps its deepest crisis since its inception in 1948.

More than 7 million people are currently on waiting lists for medical procedures — nearly double the amount since the start of 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic.

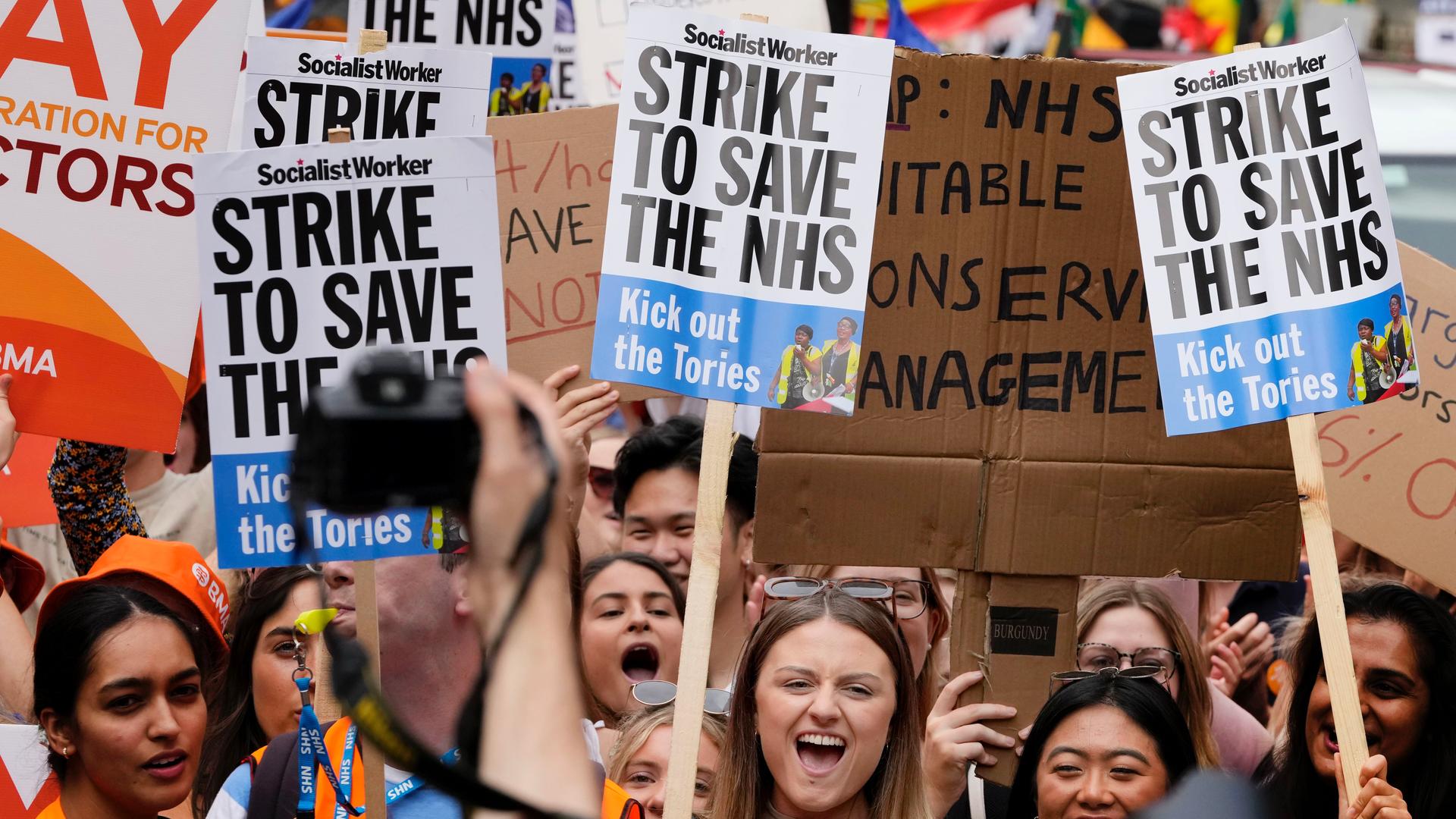

Thousands of NHS staff members have also been striking over calls for pay increases.

Last month, the conservative government said it would give junior doctors a 6% pay increase, well short of the 35% workers insisted is needed just to bring them back to the same pay rate they received in 2008 once inflation is considered.

Many seek work abroad in places like Canada and Australia, where wages are higher.

Harry Eccles, a nurse and union activist working in southeast England, in large blamed the ruling conservative government for the current crisis. He accused the party of intentionally neglecting the NHS as the party leans into the private sector.

“There’s a lot of money that can be made in health care, and we really want to protect our NHS from that,” Eccles said. “It feels a little bit like the vultures are circling, and they want [the NHS] to fall so that they can pick up the pieces and sell it off for quite a lot of money.”

Public health care spending has risen by an average of less than 2% in the last 10 years, less than half the amount in the decade before. Meanwhile, the Conservative government has openly toyed with the idea of charging patients about $25 to visit a doctor as a means to keep waits.

In January, Britain’s former Health Minister Sajid Javid said he felt the NHS couldn’t keep running as is.

“I don’t think the model of the NHS as it was set up some 70 years ago is sustainable for the future,” Javid told Sky News. “The world has changed, and the NHS has not moved on.”

In a proposal, Javid cited Ireland and Norway as examples of countries that charge patient fees as a means to control costs and keep wait times down.

But for most people in Britain, charging for health care would be a grave mistake.

An Ipsos poll released last month found that nearly three-quarters of all Britons think the NHS is crucial to British society, and everything should be done to maintain it in its current form.

“We must never forget what it was set up for in the first place,” said 75-year-old Aneira Thomas.

Thomas, born just after midnight on July 5, 1948, was the first NHS baby. She was named after the NHS founder Aneurin Baeven, a Welsh Labour Party politician and Britain’s former health minister.

“He was a giant of a man,” Thomas said. “I often use the phrase said by Martin Luther King, the American activist, ‘I have a dream.’ So did Nye Bevan. And he had a vision of creating a health service for the people of Great Britain.”

Despite its recent struggles, Thomas said she’s hopeful about the future of the NHS: “It was there for my first breath, and please, God, it will be there when I take my last breath.”