GBH Advisory: This project contains descriptions of violence and dehumanizing language to reflect the horrors that Black people and Native Americans were routinely subjected to during the era of American history when slavery was common. We recognize such language may distress some readers. Discretion is advised.

A narrow red brick path winds through the sidewalks of downtown Boston, connecting 17 historic sites tied to the city’s colonial history as the incubator of the American Revolution.

But the red line of the Freedom Trail also could symbolize the blood of enslaved people who helped make that revolution possible.

Boston is a cradle of American history, and 4 million people a year visit the historic churches, graveyards and parks that make up the Freedom Trail to learn more about the country’s origins.

But rarely do they hear the underbelly of that story: that slavery touched nearly every aspect of the society and the economy of Massachusetts during that period of time. But that is now changing.

In the 1700s, enslaved people likely accounted for about 10% of Boston’s population, according to the city’s tally. An unnamed French writer visiting Boston in 1687 wrote, “You may … own Negroes and Negresses; there is not a house in Boston, however small may be its means, that has not one or two.”

The malicious tentacles of slavery in the Bay State were widespread, although Massachusetts was not home to massive agricultural plantations like in the Southern colonies.

Boston thrived on shipping that involved transporting enslaved people or the products of their labor. The colony had a huge rum industry, made possible by the sugar harvested in the slavery-riddled Caribbean. And enslaved people in Central and South America mined the silver that Paul Revere used to manufacture his iconic kitchenware.

And those connections can be tied directly to sites along the 2.5-mile Freedom Trail: in the wood harvested by enslaved workers to build the USS Constitution; in the unmarked graves at Boston’s old cemeteries and in the history of Boston Latin School, where enslaver Nathaniel Williamsserved as one of the first schoolmasters.

“We kind of give ourselves a lot of credit for being the first state to banish slavery,’’ he said. “But we were also the first state to make it legal.”

Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery, with the adoption of the 1641 “Body of Liberties,” which set out the rules under which a person could be enslaved. Slavery was abolished in the 1780s through a series of court cases brought by enslaved people.

L’Merchie Frazier, former director of education and interpretation for Boston’s Museum of African American History, said the interpretation of the historic sites on the trail, installed in the 1950s, has completely ignored the role of Black people.

“Whose freedom are we trailing and are we tracing as we walk on those bricks?”

“Whose freedom are we trailing and are we tracing as we walk on those bricks?” she asked.

GBH News reporters worked with a group of Boston University journalism students to document the lesser-known history of slavery at each of the sites along the Freedom Trail. For several months, students dug into archives and worked with researchers to piece together information.

Some of the sites have done a lot of this work themselves and were able to share their findings; others, like the Old Corner Bookstore and the Boston Common, are essentially unmanaged and required students to dig through troves of documents and read historical texts looking for clues. While very little of what was found was previously unknown, there’s no easily accessible place to find all the information collected in one place.

View the interactive map:

The Enslavement History of the Freedom Trail

Suzanne Segura Taylor, the executive director of the Freedom Trail Foundation, said her organization has long trained guides to mention slavery on the tour.

For example, the training materials direct guides to discuss the small grave marker beside the tomb of John Hancock, a two-time Massachusetts governor made famous for his signature on the Declaration of Independence. The small grave carries the name of “Frank,” described as a servant of Hancock’s and who was almost certainly enslaved, historians agree.

“Those are the things we say that must be talked about,” she said.

But, she said, more can be done to elevate the story of Boston’s slave history, and she hopes to share GBH’s findings with her tour guides.

The Freedom Trail Foundation is just one of countless organizations leading tours of the historic sites. Last month, a GBH News reporter took a 2 1/2-hour walking tour with a private company that covered all 17 sites and never once mentioned slavery.

“There’s a lot of people out there conducting tours that we don’t know what their outlines are, what they’re required to discuss on their tours,” Taylor said.

Frazier said the story that tourists hear about colonial Boston depends on the guide.

“Previously on the Freedom Trail, the only mention of any Black person was Crispus Attucks — and not his history, just that he died on March 5, 1770,” she said.

Attucks, the first person killed in the Boston Massacre on that day, is buried with other victims under a commemorative stone in the Granary Burying Ground, beside revolutionary leader Samuel Adams. GBH followed several tours through the burial ground and the massacre site and heard no mention that Attucks — the child of an enslaved Black father and a Native American mother — had once been enslaved and advertised as a runaway.

Frazier also points out that the story of enslaved people in Boston is not just a story of victimhood. It is also the story of people working together to educate themselves, learn skills and try to build wealth — and fight for their freedom.

It was “a strategized, networked, organized movement to secure their voices, their land, their property,” she said. “If you leave out that narrative, that expanded narrative, of Black and Indigenous people here, you have really done a woeful job of delivering history. Especially in terms of considering the principles of democracy.”

While there is growing acknowledgement of the city’s ties to slavery on the Freedom Trail, the public-facing recognition of it is intermittent. For example, organizers at King’s Chapel, a stone chapel founded in 1686, launched an effort a few years ago to grapple with its history. Many of the founding members, and many of the donors to the construction of the church, were slaveholders, slave traders or otherwise made their money from the work of enslaved people.

Signs around the church now explain those connections, and the chapel recently approved a massive transformation to install a monument to the 219 enslaved people linked to the congregation’s history.

Watch how King’s Chapel is reckoning with its ties to slavery:

But just outside the church, the city-owned King’s Chapel Burying Ground provides no details about slavery on its signs, even though some of the most illustrious names on its tombstones commemorate people who owned slaves, including John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts.

A “First Governor” plaque in the burial ground marks the family tomb and tells the story of Winthrop’s career, noting that he was “considered religious, prudent, conscientious and pious.” No mention is made of the fact that the governor sent soldiers to sack a Pequot settlement in 1627, taking hundreds of Native American prisoners, many of whom Winthrop sold, gave away as slaves or kept for himself.

Beth Anne Bower, credited as the historical research consultant on those signs, told GBH News that when the placards were made two decades ago, exploring connections to slavery “was not the conversation.” Instead, she said, she was encouraged to focus on the “diversity” of people buried there, highlighting women business owners and French migrants.

The current recognition that “we should start confronting this history” was not part of the mission for those signs, she said. “It should have been.”

Walking past the site of Boston Latin School — the oldest school in the nation — visitors would not learn that Nathaniel Williams, one of the school’s first schoolmasters, enslaved two people identified as Richard and Hagar. This fact is not mentioned on the school’s own website or on the mural painted on the sidewalk on School Street, which is named for Boston Latin. But these key details are available on other city websites.

Increasingly, the sites along the Freedom Trail — which are curated by different groups, including the National Park Service, the city of Boston, individual congregations and stand-alone nonprofits — have begun telling the stories of the foundation of enslavement that the city’s history stands upon.

The USS Constitution Museum in Charlestown, which receives hundreds of thousands of visitors a year, leads visitors through a hands-on description of how the ship was conceived and built.

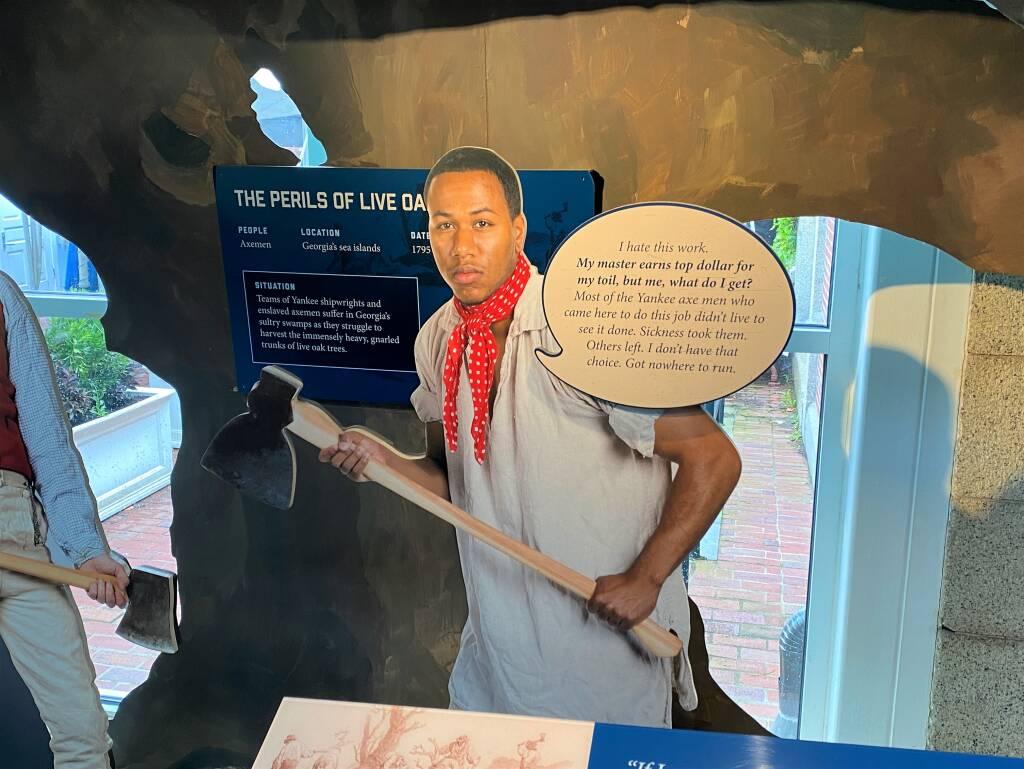

Dr. Carl Herzog, the historian at the museum, told Boston University students that the “live oak” — a particualry impregnable species of wood — that the US Navy sought to build the boat with in the 1790s came from Georgia’s St. Simons Island, where it was harvested by enslaved workers. In a blog post published on the museum website late last year, Herzog detailed the use of this wood: “Paying enslavers for the forced labor of enslaved people was an expediency that Navy officials and contractors saw as fundamental to the job. Thus, enslaved people were essential to the construction of naval warships built to secure the very American freedoms they were denied.”

The museum exhibit includes a modern life-sized photo of a Black man dressed as an “enslaved” worker carrying an axe. The attached sign says, “I hate this work. My master earns top dollar for my toil, but me, what do I get? … [White workers] left. I don’t have that choice. Got nowhere to run.”

Old North Church, where the lanterns were hung in the steeple “one if by land, two if by sea” to launch Paul Revere’s famous ride, has rewritten its own materials to expose the slave ties of the donors who funded that steeple.

The Old State House has an exhibit about the petitions enslaved people submitted to the Legislature in the 1700s asking for their liberation and reparations.

Stepping off the Freedom Trail, visitors can find even more of this history.

The National Park Service leads tours on a 10-stop Black Heritage Trail that features an alternate slate of sites curated by the Museum of African American History, including the African Meeting House — the nation’s oldest Black church building — and the John J. Smith House, home to a leading abolitionist who helped liberate Shardrach Minkins, an enslaved man from Virginia arrested in Boston in 1851 under the Fugitive Slave Act.

And the city of Boston has unveiled an exhibit inside Faneuil Hall to document some of the enslaved people who lived here and to highlight “Boston’s complicity” in the slave trade. The location was chosen specifically to elevate the fact that Peter Faneuil, who built the building donated to Boston in 1742, was one of the most active slave traders in the colony.

Some social justice leaders, like Imari Paris Jefferies, chief executive of Embrace Boston, who led the 2022 installation of the new civil rights memorial on the Boston Common, say this recognition is long overdue.

“To have more of these historic and legacy institutions on the Freedom Trail tell a holistic story about Boston’s — and by default America’s — involvement and engagement in this dark part of our history is an important part of reconciliation,” he said.

This story originally appeared on GBH’s Morning Edition.

Related: Benin is building a theme park to remember slavery — is history up for sale?

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?