The lawns of the United Nations headquarters in New York were dotted with yellow yoga mats as hundreds of people gathered on Wednesday morning to stretch together. Among them was Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi — leading International Yoga Day celebrations as part of his three-day trip to the United States.

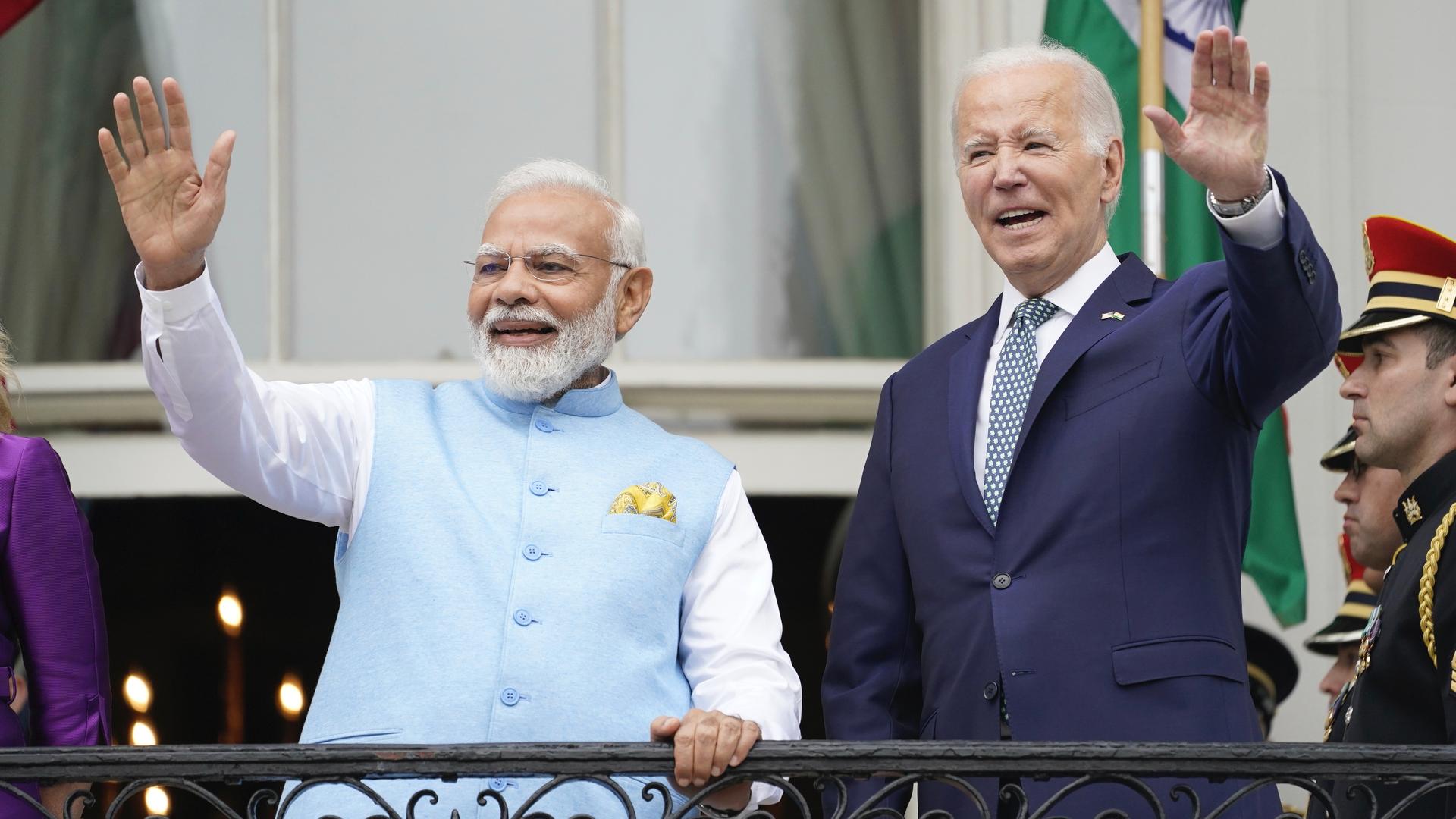

The Indian leader has visited the US several times since taking office in 2014. But this trip is a rare state visit — the highest diplomatic honor for a foreign leader. President Joe Biden has only invited two other leaders — French and South Korean — for such visits, and Modi is only the third Indian leader to receive such an invitation.

On Thursday, Modi will hold bilateral talks with Biden and address a joint session of Congress, followed by a lavish dinner reception at the White House. The US and India have long enjoyed warm relations, but this visit is particularly momentous.

“Every once a decade or thereabouts, you have a visit that really moves the ball forward,” said Richard Rossow, chair of the US-India Policy Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “And it feels like both governments are talking about this visit as kind of along those lines.”

Despite Delhi and Washington not seeing eye to eye on some key issues, the Biden administration has bestowed Modi with the honor, even as human rights groups raise concerns about Modi’s allegedly anti-Muslim policies back home.

In India, Modi supporters see the visit as a moment of pride. One pro-government news channel used the hashtag #ModiMagicInAmerica with its anchor Arnab Goswami saying that the US had more at stake than India.

“It is just one more telling statement, ladies and gentlemen, of how India’s place in the world has risen in the Modi years,” Goswami declared during his news segment.

The US and India have had strong people-to-people ties for years, with a large and influential Indian-American diaspora. Trade between the two countries has also been flourishing for decades. But Modi’s visit this week could see the two nations join hands to strengthen another pillar of their partnership.

“There will be a great deal of focus on defense and security cooperation, as well as technology cooperation,” said Lisa Curtis, director of the Indo-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. “The US is setting the stage for an announcement that it will co-produce jet-engine technology with India, which is a huge deal. Only a handful of countries have this kind of technology capabilities.”

India is also close to signing a deal to buy MQ-9B armed surveillance drones from the US. Earlier this month, the US defense secretary, Lloyd Austin, met India’s defense minister, Rajnath Singh, in Delhi to set up a road map for defense industry cooperation.

While the US wants to help India enhance its military capabilities, Curtis said, “Part of the goal here is to wean India away from its dependence on Russian military technology.”

About half of India’s weapons imports come from Russia. This defense partnership is the cornerstone of the close ties between Delhi and Moscow, which date back to the Cold War. It’s also why India has not condemned Russia for invading Ukraine. While the US isn’t particularly happy about this, Curtis said it has largely accepted it.

“India is too important for the United States over the longer term, and so, there is a willingness to set aside the US-India differences over Russia,” Curtis said.

On the Indian side, there has been a “sea change” in the outlook towards the US, said Rajan Menon, director of the Grand Strategy Program at the Washington-based think tank Defense Priorities.

In the 1970s, relations between the two were “frosty,” Curtis said. During the India-Pakistan war of 1971, Washington sided with Islamabad as Delhi turned to Moscow. But over the past two decades, and under Republican and Democratic administrations, the US has warmed up to India. In recent years, the two nations have also been pushed toward each other by another Asian giant.

“China is playing matchmaker here,” Rossow said.

Tensions between the US and China have been at a historic low. Meanwhile, India and China are engaged in a standoff over their disputed border in the Himalayas, where fighting breaks out sporadically. Besides security concerns, Rossow said, Biden and Modi will also discuss cooperation in strategic commercial sectors to keep China’s rise in check.

“Areas that are important for global growth and technology evolution, and those areas where China has a market moving position, so critical minerals and rare earth, 5G and 6G, undersea cables, artificial intelligence, quantum, even commercial space exploration,” Rossow said. “Can we break China’s stranglehold and their ability to use these things as commercial threats against other countries?”

Menon said that this is a “new chapter” in US-India relations and one that is “largely China-driven.” And while India is welcoming deeper ties with the US, it is also careful not to upset other nations.

“India’s government will have to balance how it handles the relationship with the US with its long-standing relationship with Russia,” Menon said. “It doesn’t want to alienate both China and Russia simultaneously. So, there’s a kind of a delicate dance going on.”

In India, Modi’s visit is being seen as proof that Delhi has played its balancing act between Washington and Moscow well.

As the White House prepares to welcome Modi for a state banquet, human rights groups are protesting against his visit, saying his policies back home target religious minorities. Modi was once denied a US visa for his alleged role in anti-Muslim riots in 2002.

“[The US] talks a good game on the human rights front, and sometimes, we’re sincere, but when it comes to concrete interests, we’re perfectly willing to put them to the side,” Menon said.

Rossow said that the Biden administration will raise human rights concerns with Modi, but in private.

“They’re not going to want to tip over the applecart by pushing too hard,” he said, because the broader relationship with India is too important.

In 2006, then-Sen. Biden laid out a grand vision for US-India relations.

“My dream is that in 2020, the two closest nations in the world will be India and the United States. If that occurs, the world will be safer,” he said then.

“I don’t think we’re quite there; it is more aspirational right now,” Curtis said.

India and the US are not allies and probably never will be, she said. But they are strategic partners with mutual interests that span several areas.

Related: Amid war in Ukraine, India maintains ‘strategic partnership’ with Russia