Ukraine House in Denmark overlooks the stunning waterfront in Christianshavn, the heart of Copenhagen, with the flags of both Ukraine and Denmark waving out front.

Co-founder Nataliya Popovych hopes that visitors — Ukrainians and Danes alike — will come to the newly minted space to learn more about Ukrainian arts, culture and history.

Ukraine House opened its doors on Feb. 24, on the one-year anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

“We felt that we need to respond to the growing number of Ukrainians that are arriving in Denmark,” Popovych said while giving a tour of the new space that formerly housed the Danish Architecture Center.

“There is a growing need to help explain to Denmark and Danes what Ukraine is, and why it’s so essential to support Ukraine until victory, and we felt that it was important to open a cultural center for Ukraine, something that would be a home to Ukrainian culture in Denmark.”

There are about 37,000 Ukrainians who have migrated to Denmark since the war started, and thousands more who have lived in Denmark for decades.

Popovych said the Danish government approved the allocation of the building in October, with the shared aim to promote Ukraine’s cultural heritage and organize creative Danish-Ukrainian collaborations.

Their first major exhibition was “The Muses are Not Silent,” curated by Pavlov Gudimov, in partnership with the Ya Gallery in Kyiv, Ukraine.

“When cannons are firing during the war, [there’s a saying that] ‘muses become silent.’ But actually in Ukraine, they’re not — they’re the creative forces, the creators, the artists — and they’re very, very vocal,” Popovych said.

The exhibition, which closed on May 21, featured 50 artists across Ukraine.

The artworks — ranging from paintings to photography to sculpture to film — tell a collective story of horror and hope of life during wartime.

“Beyond the horror and shock that the artists are feeling — because by now, 15 months into the war — there’s probably no family there that has not been in one way or another touched by war,” Popovych said, “but at the same time, there are situations of humor and situations of everyday joy.”

One of the stars of the show, Dmytro Moldonavov, is a contemporary artist who lives in Parutino, a small fishing village just outside of Mykolaiv. The major port city in southern Ukraine has been badly damaged by Russian attacks throughout the war.

“February,” a self-portrait, depicts the artist seated in a chair as he witnesses people fleeing from a city under attack. On the right, a ferocious, green-striped beast spews ashes as he stands on the busts of Russian rulers: Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Vladimir Lenin, and the severed head of Vladimir Putin.

Moldonavov’s small village of about 1,500 was bombed by the Russian military for much of last year. The 56-year-old artist said the invasion was horrific but also spurred his creativity, according to a recent profile in The Guardian.

One of the first paintings he worked on at the beginning of the invasion depicts three brightly colored deer with one tilting its antlers down, entitled, “Hearing the Wolves,” evoking a sense of imminent threat.

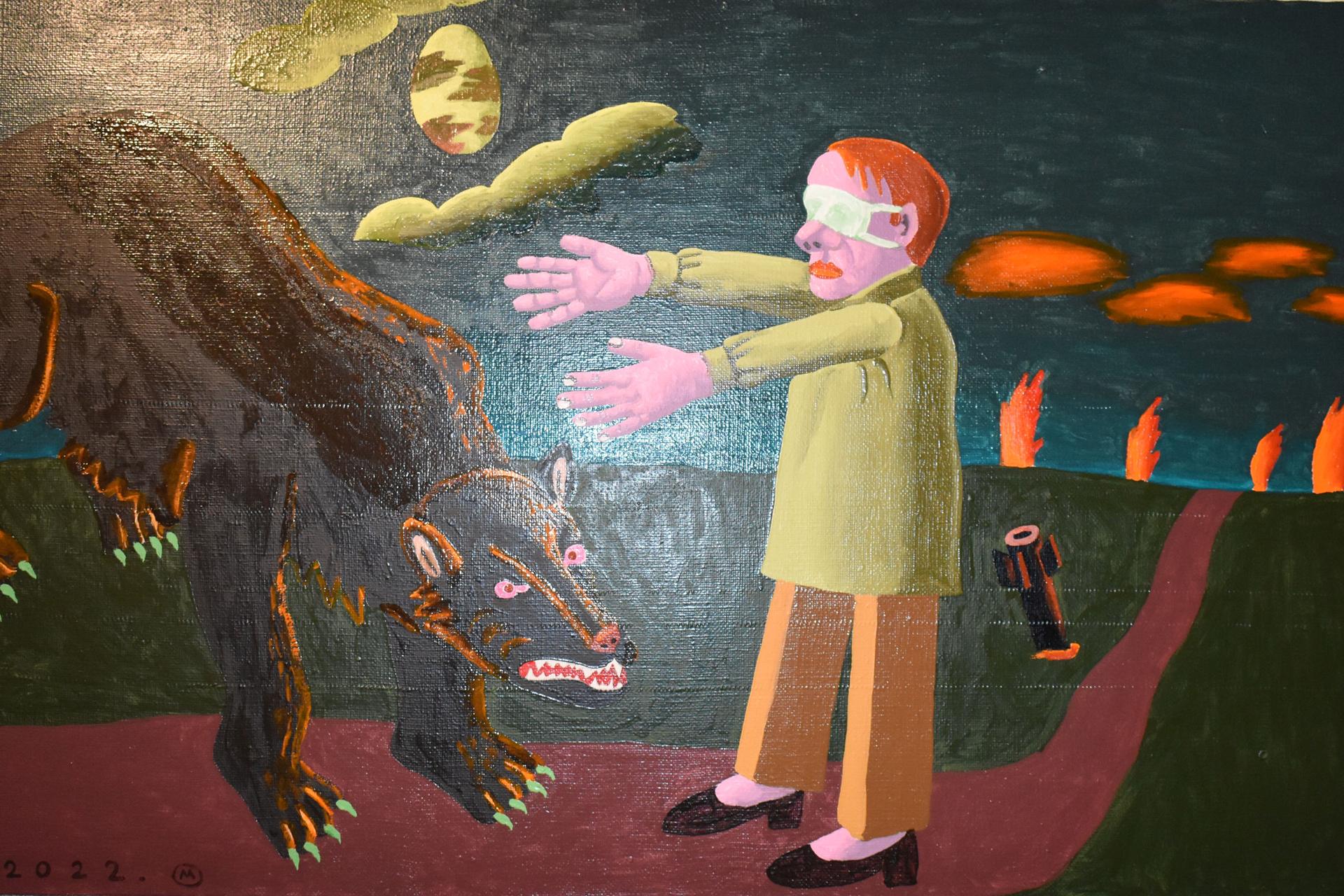

Moldovanov’s “Who is Here?” shows a blindfolded man reaching his arms toward a grizzly beast amid a field of flames.

In Moldovanov’s “Three Angels,” two women and a child appear frozen in their confrontation with a ferocious lion surrounded by flames.

“Sign Language,” a startling sculptural work by Konstantin Zorkin, also stood out among the many provocative paintings, photographs, sculptures and video installations at the exhibition.

Popovych said the abstract collection of hands morphed with human bodies and sharp objects asks the viewer to consider the language of signs and symbols during wartime. She noted that many cities torched and attacked by Russian forces — Mariupol, Bucha or Irpin, for example, later became symbols of Ukrainian resistance — and resiliance.

Polina Kuznetsova, an artist from Kharkiv, Ukraine, creates paintings that raise questions about landscape and grief.

The painting, “Desert,” depicts a world of empty houses, crosses and body bags for the dead. The artist contemplates what life may be like in a postwar landscape, and whether it may ever be safe again, Popovych said.

“While being evacuated, the only thing I could look at was the news and photos of what was happening in Ukraine. At some point, in the photographs, a lot of black bags appeared, these were bags for dead bodies. These packages were very similar to the black boats that sail across the land of Ukraine,” Kuznetsova said in a direct message on Instagram.

Kuznetsova continues with these themes in “Spring Picture,” where crosses rain from the sky onto an empty landscape, evoking images of loss and death.

The painting is based on “memories of a peaceful Ukrainian land,” she wrote, adding that before the war, she was working on a big project about dreams.

“Two fabrics are flying in the sky. Pink fabric is a dream symbol,” she said, and the black fabric represents grief.

“Black and pink collided. On a peaceful, calm landscape, crosses are falling. Black crosses turn into white tombstones. These are very simple naive symbols, but war is not something new and complex. There is black and there is white, there is love and there is grief.”

For the many Ukrainians who arrived in Denmark under the duress of war, Popovych said, Ukraine House is an invitation to deepen their understanding of their history and identity, whether they stay in Denmark or one day return home.

“You know, Ukraine before war was still already much more self-aware but still a very traumatized Soviet society. So, there are a lot of discoveries that Ukrainians [can] make on themselves in terms of our history and culture and identity,” she said.

At the same time, Ukraine House is a meeting place for everyone to “share perpsectives on what kind of future we’re all building,” Popovych added.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!