In Colombia’s capital, the ‘purple patrol’ fights sexual harassment on crowded buses

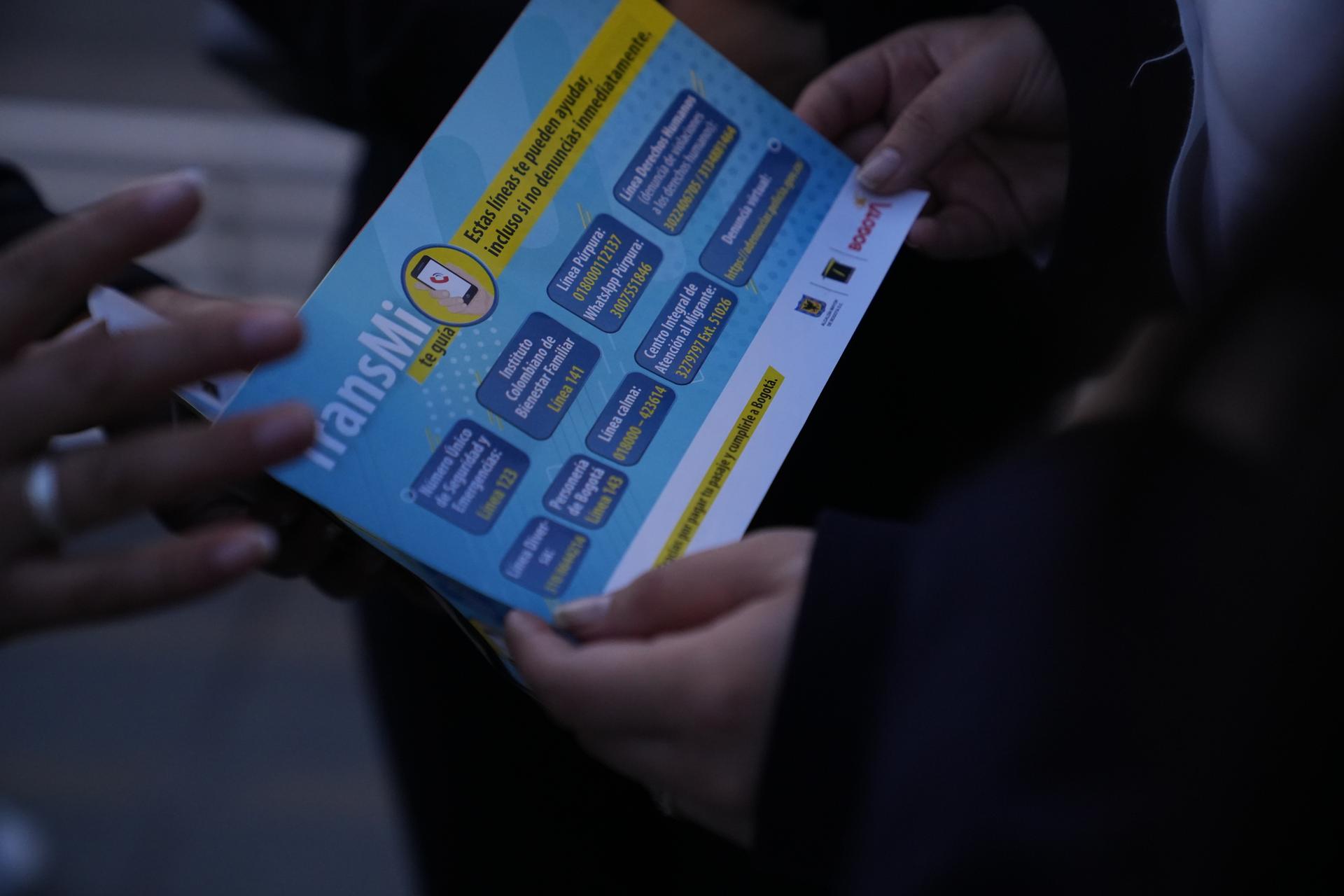

As thousands of people make their way home on the rapid bus system in Bogotá, Colombia, during rush hour, a group of female police officers hands out purple leaflets to women, encouraging them to report cases of sexual harassment.

“It gets very crowded here, and you get lots of cases of men who harass women and even touch their private parts,” police officer Alejandra Luna said, after handing out some leaflets to a group of students. “We want women to take a stand against that, and seek our help.”

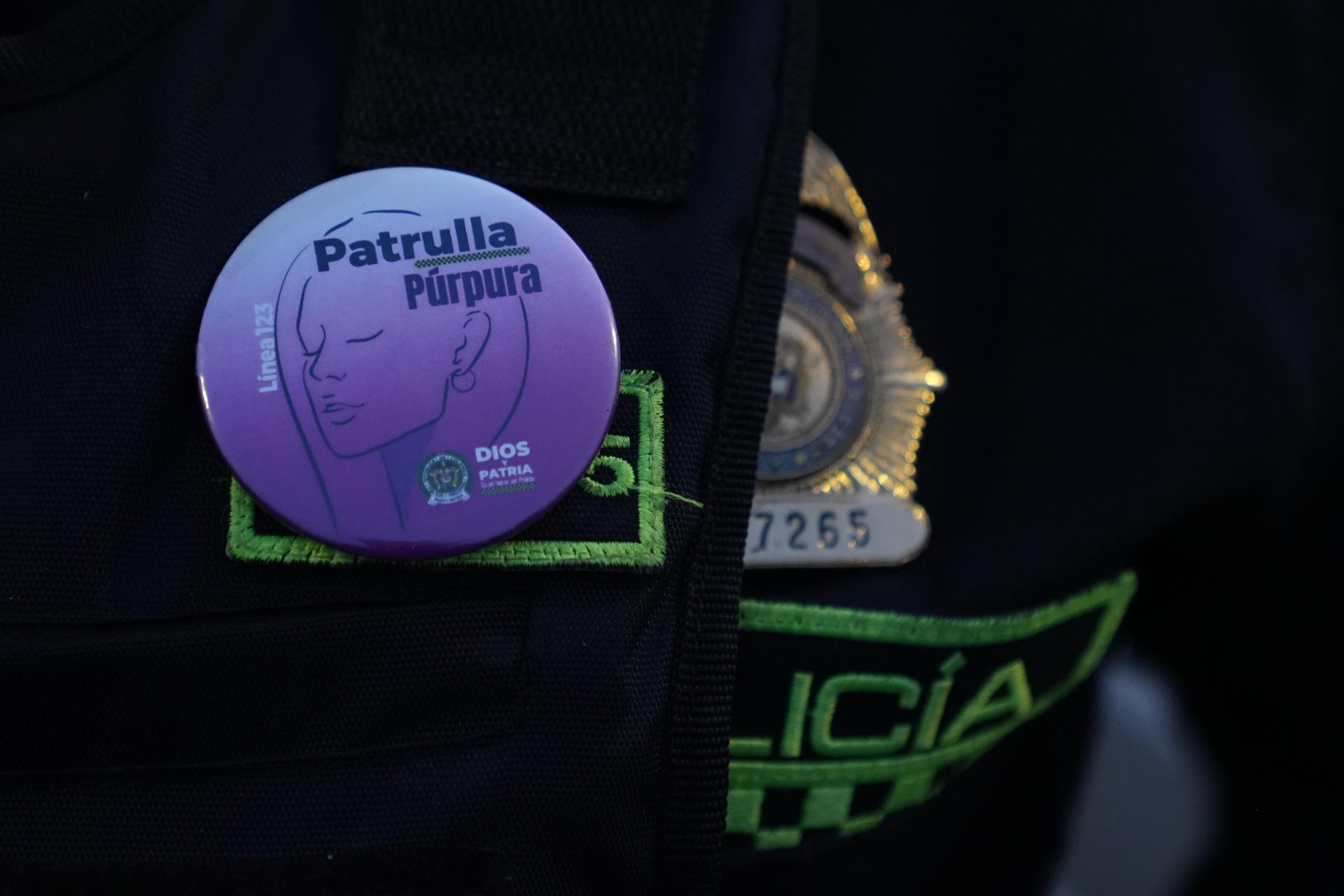

Luna is a member of the purple patrol, a group of 500 police officers in Colombia’s capital city that has been trained to respond to gender-based violence.

One of the patrol’s goals is to reduce harassment in the city’s public transport system, where last year, women reported more than 1,000 cases of unwanted touching and groping.

These kinds of assaults on women aren’t just a problem in Colombia. In 2021, the Ipsos research company conducted a survey with women in 15 countries that included the United States, Italy, India, South Africa and Brazil. Of those who participated, 80% said that at some point in their lives, they had experienced sexual harassment in public spaces, with about 40% saying they had experienced “unwanted kissing, touching and groping.”

Some places like Mexico City have tried to reduce assaults on women by creating subway cars and taxis that are for females only. While in the London Underground system, signs tell people what to do if they see a woman being harassed.

In the Colombian capital, authorities are trying to reduce harassment with better policing, but also by trying to get bystanders more involved.

“We need people to continue to report these crimes,” said Lt. Col. Ana Gutierrez, the director of Bogotá’s purple patrol. “We can’t be indifferent to what is happening to women here, and elsewhere in the world.”

The purple patrol tackles harassment through information campaigns, like with the leaflets that its officers hand out at bus stops, but also by taking measures that make it easier for women to file complaints —and they arrest offenders.

The group was founded in November, and Gutierrez argues that its strategies to stop sexual harassment are already having an impact. She pointed out that in the first three months of this year, complaints for groping and unwanted touching increased by 20%. Also, the number of related arrests doubled.

“That’s a sign that people are trusting the police more,” she said. “And that they are learning that harassment is a real crime.”

Some of the leaflets that her officers hand out include QR codes that link to a website with videos showing people how to identify situations of sexual harassment and respond to them appropriately.

They were produced by Right To Be, a nonprofit group based in New York, which partnered with makeup company L’Oreal to create an international anti-harassment website.

“The police are rarely around when harassment happens,” said Right to Be’s founder Emily May. “So, we thought that equipping people to take care of one another … would be a better strategy long term to address and eliminate harassment.”

In its videos and face-to-face training sessions, Right to Be teaches bystanders to respond to situations of sexual harassment by documenting them with their phones, seeking help and distracting the offenders, so that they back away from their victims. May says that these methods — which she calls the 5Ds — can help to peacefully diffuse situations in which women are being harassed.

In Bogotá, the city government is also trying to use public shaming as one of its strategies. It’s handed out thousands of small whistles that people can wrap around their wrists, and is encouraging bus riders to use them, when they see someone being harassed.

“What should most protect a woman is everyone else’s solidarity,” said Claudia Lopez, Bogotá’s mayor, during an event in which she presented the new whistleblowing scheme. “It’s the attacker who should be embarrassed, not the woman who is attacked.”

Related: Colombia’s police come under fire from drug trafficking groups