On a scorching-hot day in Naples, Italy, this past summer, I tried to picture my grandfather, Dr. Manuel E. Lichtenstein, walking these same bustling streets during wartime.

Did he get lost in the maze of this ancient port city? Walk these same arched alleyways with views of the sea? Pass this same quiet window with the curtain blowing in the midday heat?

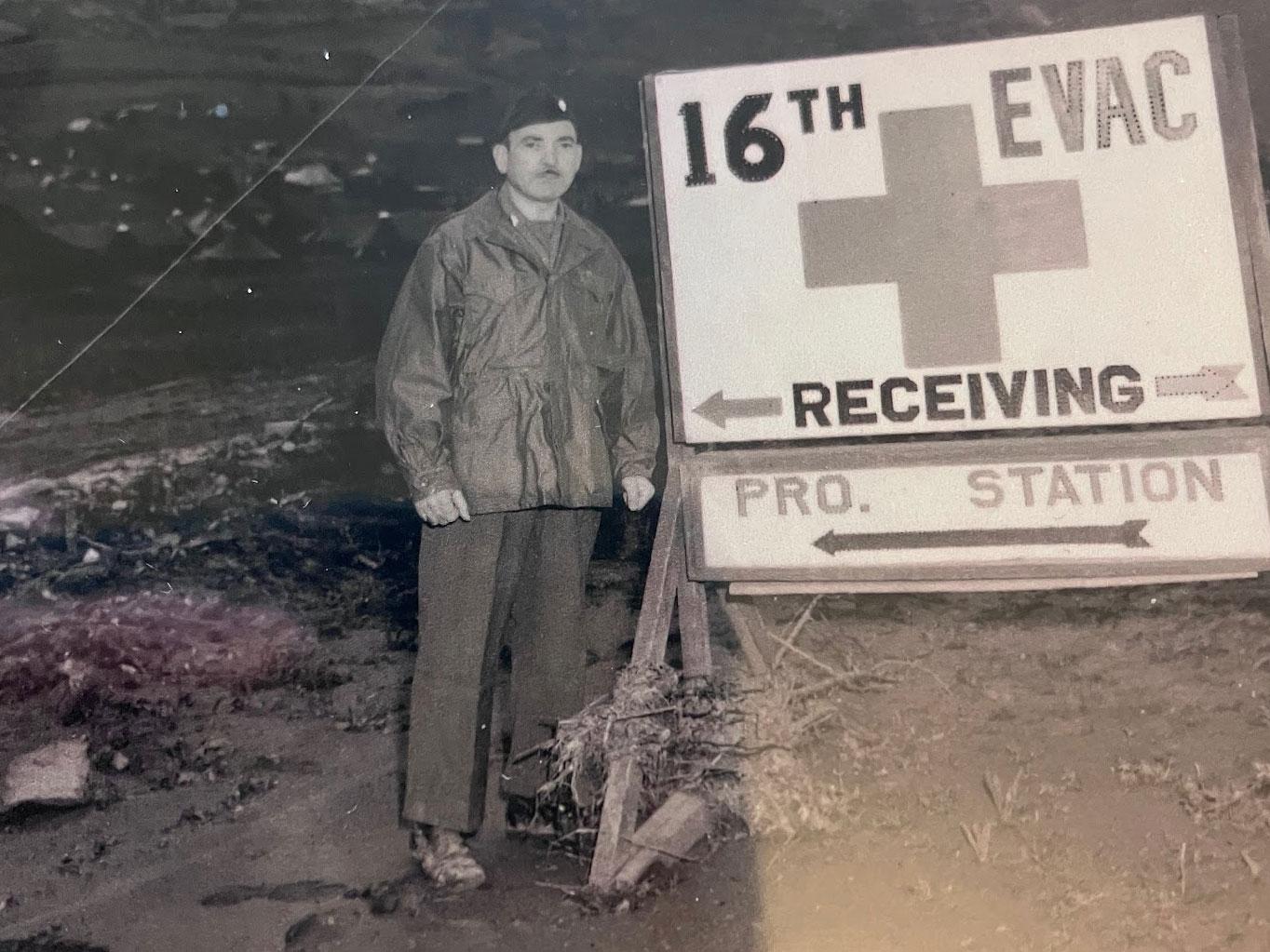

Growing up, I always heard stories about the three harrowing years my grandfather spent as a chief surgeon with American forces — setting up field hospitals in southern Italy during World War II. He met with top generals and won prestigious awards.

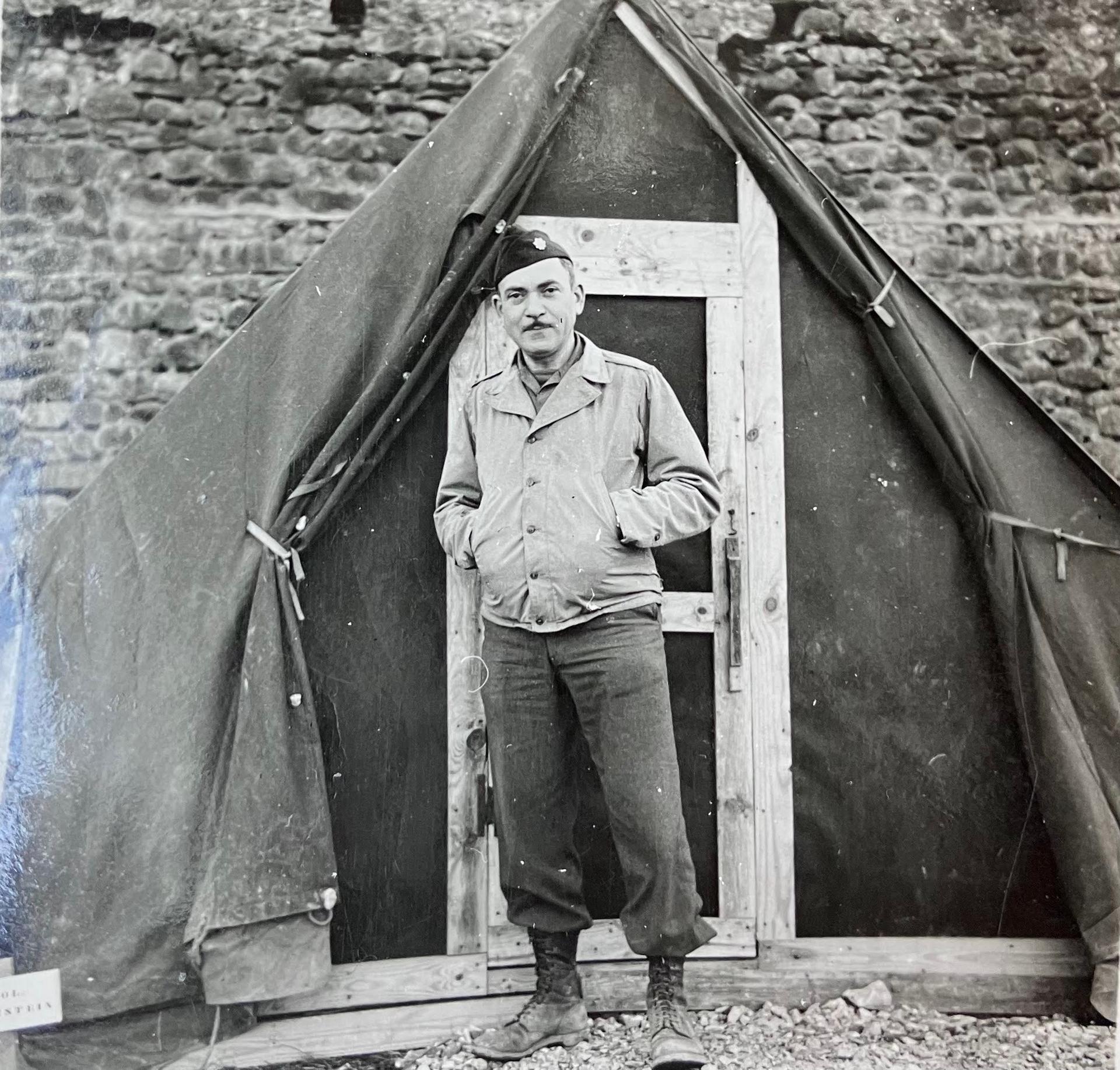

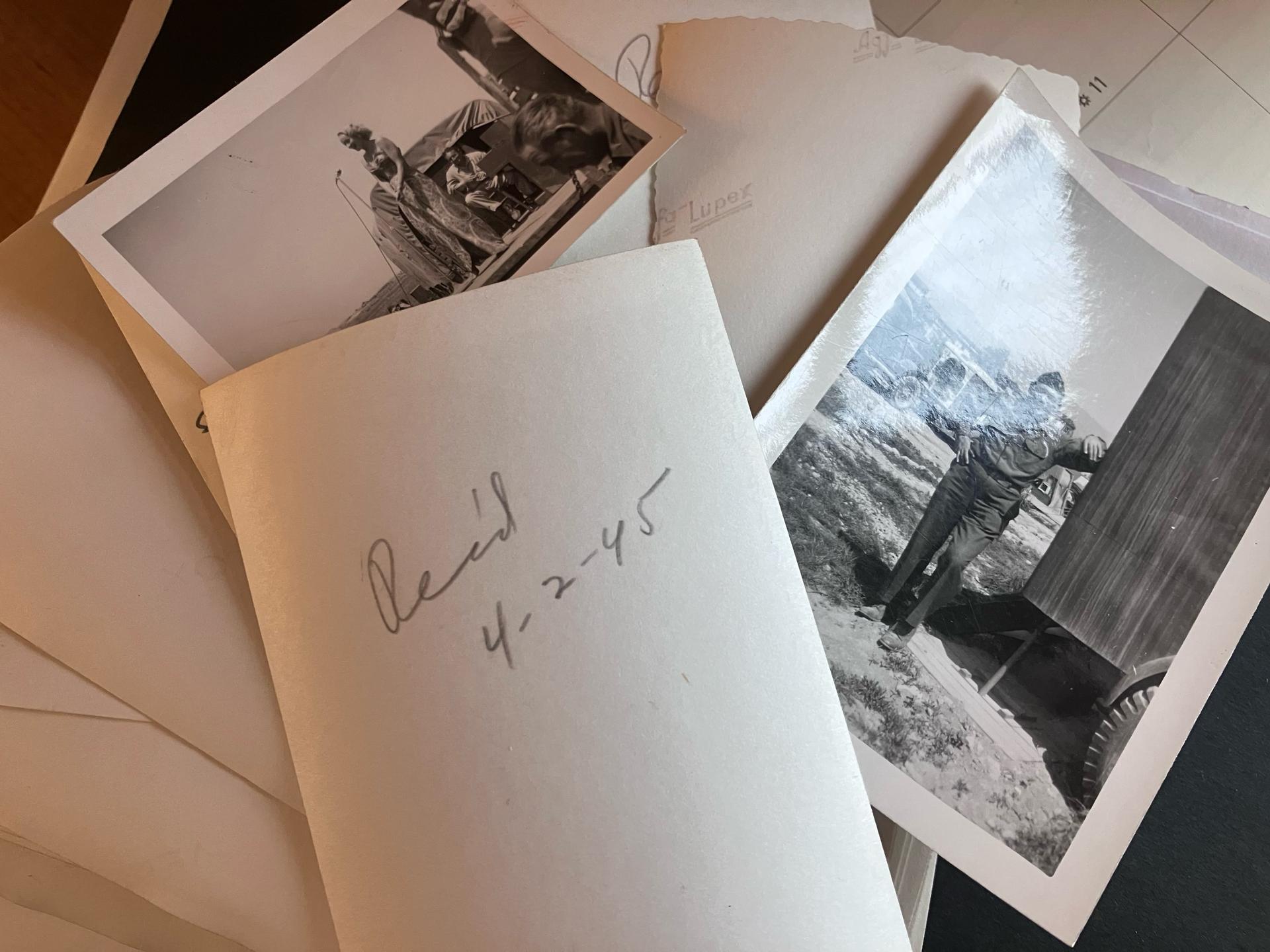

But when I rediscovered an inherited wooden box filled with hundreds of black-and-white photos taken by my grandfather — of simple moments with everyday people — it revealed a much different view of life during wartime, beyond the front lines.

It turns out, my grandfather was an “amateur photo bug” who carried his Kodak camera everywhere, according to my dad, Richard M. Lichtenstein, the youngest of three boys.

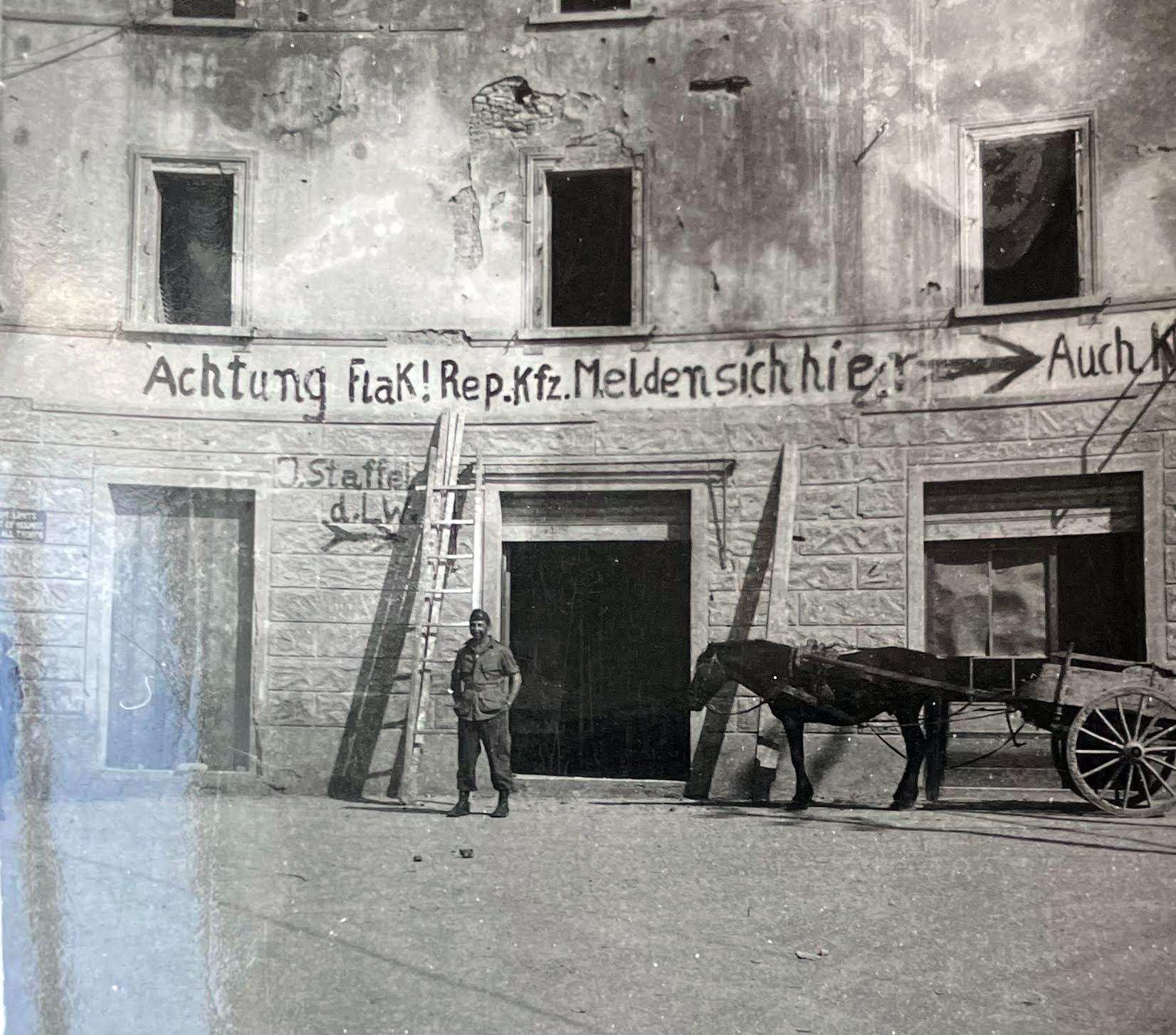

When the Americans entered Italy in 1943 to take down Adolf Hitler, the leader of Nazi Germany, my grandfather, who was nearly 44, already felt moved to join the efforts — and he brought his camera with him.

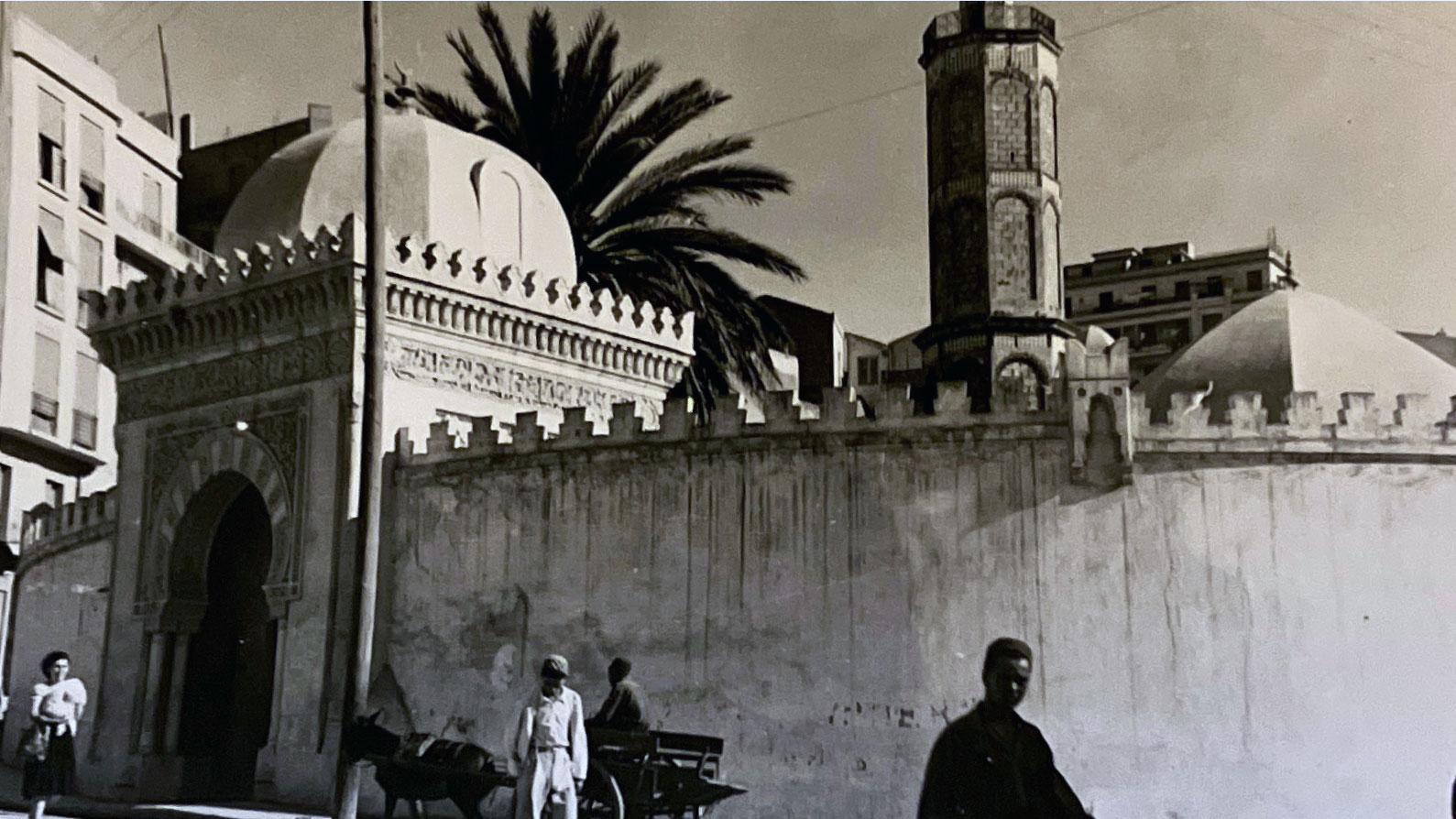

He left Chicago in April of 1943 to serve as the chief of surgical service in the 16th Evacuation Unit with Michael Reese Hospital, training in Algeria for five months before heading to southern Italy to set up field hospitals that moved with the front lines from Caserta to Cassino to Salerno to Florence to Anzio.

It was just like that hit TV show from the 1970s and 1980s, “Mash,” my aunt, Fran Lichtenstein, now 92, told me.

“He went to war because he felt that was his way of protecting not only everybody else’s family, but his family, because he really felt that Hitler was just a horrible, horrible person. And this was a horrible thing that was happening,” she said.

Life on the front lines was harried and hectic. It amazed me to discover that my grandfather still managed to find the time to interact with local people, documenting small, simple moments of everyday life in photos, many of which he mailed home to his family. Others he developed later, after the war.

The photos I found were slightly curled and still nested in the same position they were in when my Aunt Fran organized and stacked them years ago. After sifting through them all over the summer, several felt especially poignant because they capture such fleeting, yet meaningful, noncombat encounters.

Like soldiers floating down a gondola in Venice.

Or the one with four teenage boys hanging out on a busy Salerno street corner.

Or a chaotic urban street scene with a trolly passing through amid bicycle riders and pedestrians.

Or the picture of three young boys riding donkeys in the Algerian desert.

Another one shows a pair of nuns midstep in front of a church in southern Italy.

A snapshot of two women standing in a bustling market in a town square, wearing coats and holding baskets and bags, looks like a typical shopping scene. The women appear to be at a shoe stall.

Another is a portrait of a little girl holding a baby.

My dad, now 88, was just 10 at the time — and quite naive, he said, when his father went off to war. And these photos — hundreds of them in this wooden box alone — opened his eyes to a more complex and layered reality, where ordinary moments exist amid the horrors.

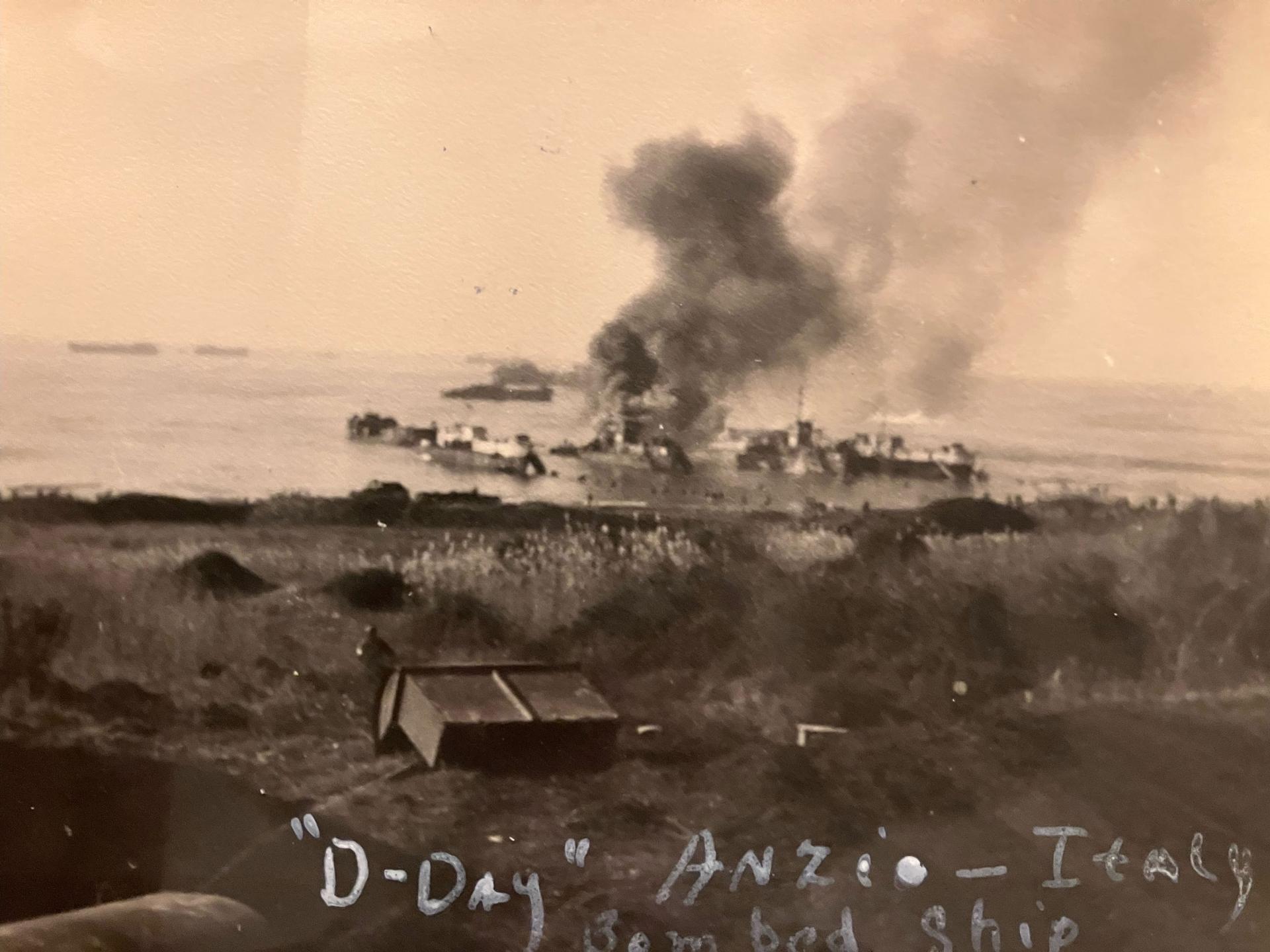

He recalled seeing one photo of bombed LSTs — landing ship tanks — that his father took along the shores of Anzio, where a fierce, protracted battle there against the Germans left 4,400 soldiers dead and another 18,000 wounded.

“I have a picture where, in one line of these LSTs, it got struck — my dad actually took the picture — he must have been about maybe 50 or 100 yards away. So, you can see that it was pretty close for comfort.”

This melancholy photo taken in a church speaks to the death and loss.

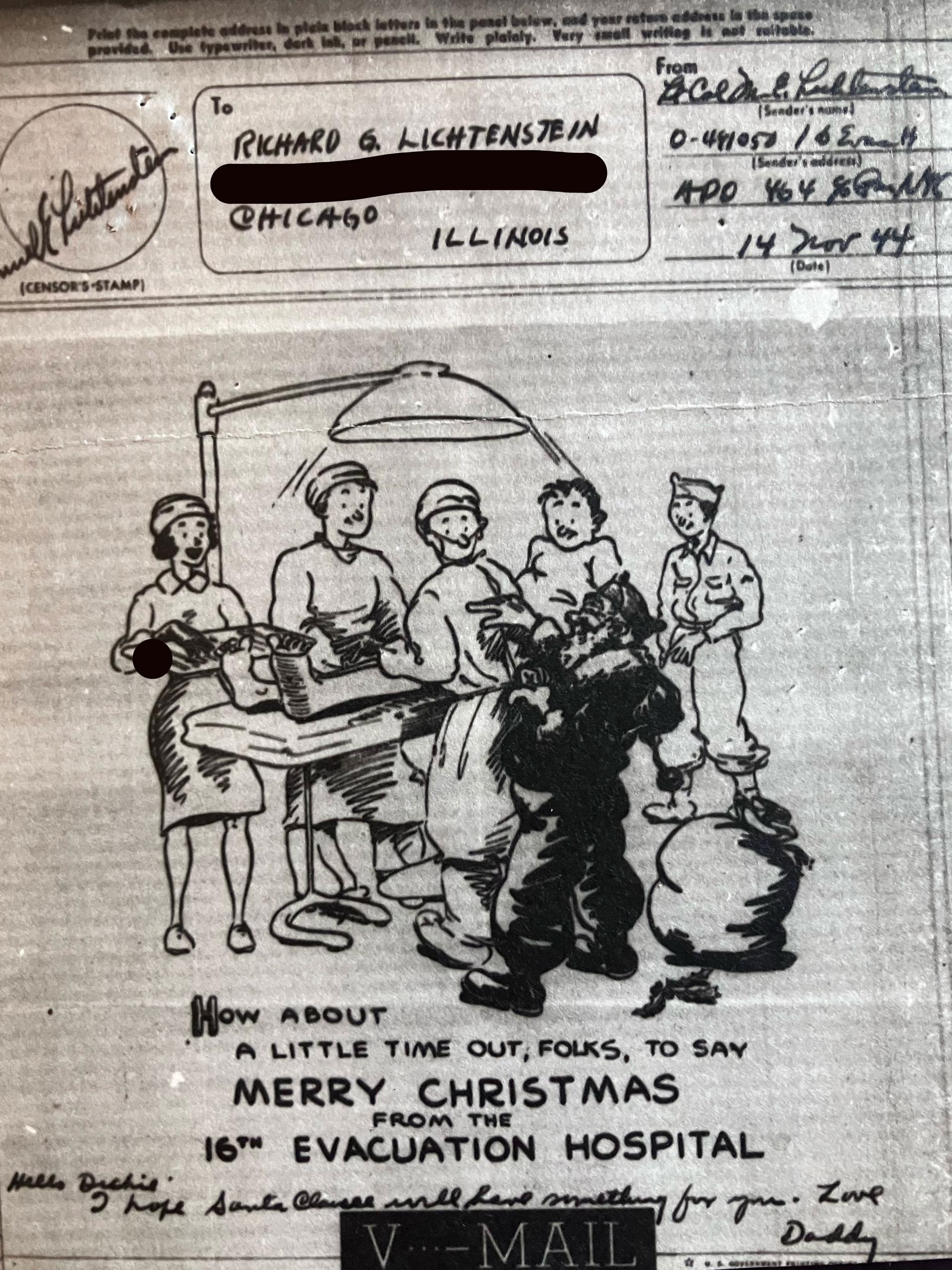

During the years my grandfather was overseas, he kept in close touch through V-mails, short for “Victory mail,” a military postal service used during World War II for expedited communication with loved ones back home.

My grandmother, Isabelle Lichtenstein, carefully labeled each photo on the back with a simple note that read “Rec’d” along with the date, and most had no further captions.

My grandfather rarely shared details about the gruesome nature of his work — stitching up the weary wounded for weeks at a time — but he did talk about some of the lighter moments.

Aunt Fran showed me one photo of my grandfather alongside Jascha Heifetz, a famous Russian Jewish American violinist who visited their hospital unit while touring with the United Service Organizations.

He met with Pope Pius XII in Italy, my dad said.

And after the war, my grandfather received a bronze medal from Gen. Mark Clark on behalf of all who served in the 16th Evacuation Unit.

He traveled with his wife, Isabelle Lichtenstein, to Brazil and Argentina to receive awards for training their medics, too. And they even had a fabled dinner with Argentina’s leader, Juan Perón, and his wife, Eva Perón (the subject of the Broadway musical “Evita”), according to my Aunt Fran. Years later, they continued to receive New Year’s greetings from the Peróns.

When the war ended, my grandfather returned to Chicago and continued to perform surgeries and taught future generations of medical students at the Cook County Graduate School of Medicine as well as Northwestern University.

My Aunt Fran said Michael Reese Hospital welcomed him back but that they gave him “late operating hours,” suggesting the staff who stayed behind during the war had mixed feelings about his return. So, he made a shift to the then-Norwegian American Hospital where he was the chief surgeon until his death at the age of 77 in 1977.

I was only 2 when my grandfather died, so I rely on these stories passed down to me from living relatives to convey the essence of his spirit.

Throughout his life, my grandfather’s brushes with fame never went to his head, my dad said. His faith ultimately grounded him as a surgeon.

“His healing went like this: Many doctors or religious people might say, ‘Oh, I healed this person.’ But my dad never said that. He said, “Do the surgery, I stitch ’em up, and God heals them.””

My grandfather’s photos are a reminder that even amid the horrors of war, respect for humanity endures.

Thanks to Hillary A. Lichtenstein for archival research and support.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?