The Marina Project is a vast memorial and tourist complex under construction in Ouidah, a coastal town in the Republic of Benin in West Africa. The country hopes to market itself as a major destination for Afro-descendant tourists in the diaspora. Neighboring Nigeria and its population of 220 million potential visitors also makes serene and diminutive Benin an enviable location for large-scale tourist attractions.

The waterfront development is located at what was the main slave port for the Bight of Benin. From this region almost 2 million enslaved Africans departed during the transatlantic slave trade. At its height — from the 1790s to the 1860s — Ouidah was controlled by the kingdom of Dahomey.

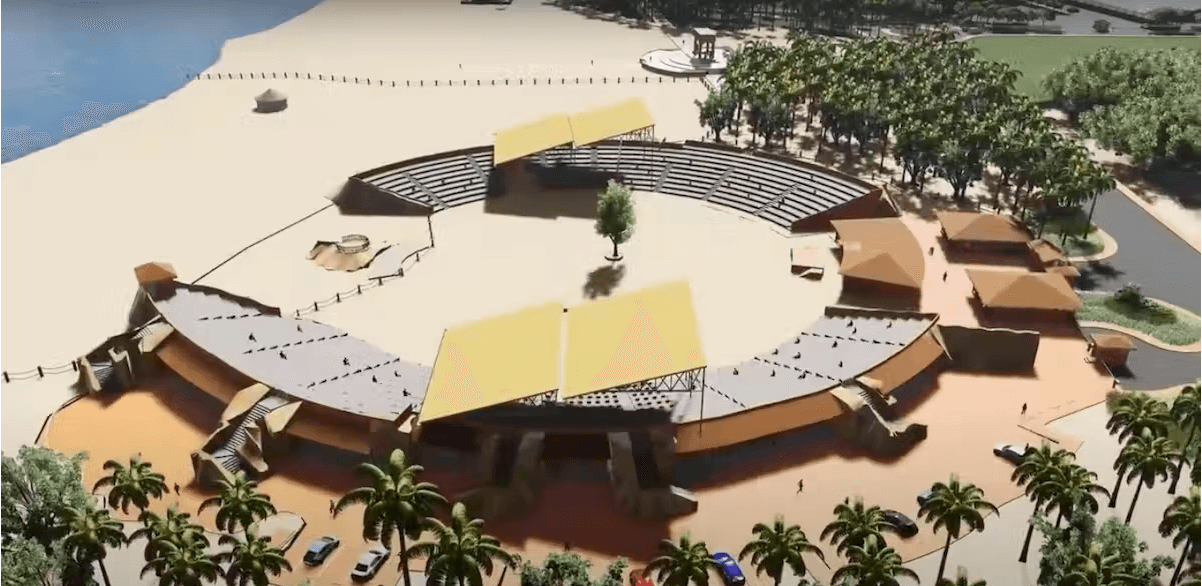

The future complex will include a hotel spa, a life-size replica of a slave ship, memorial gardens, a craft market and an arena for vodun performances. Vodun is a religion practised in Benin and among the descendants of enslaved Africans in the US, Haiti and beyond.

The local success of the Hollywood film The Woman King revealed a strong interest in this historical period, still neglected in school syllabuses.

The Marina Project could lead to a better understanding of the transatlantic slave trade. But it raises many questions. In its design and scope, it epitomizes contested directions of slave heritage tourism. The commodification of heritage may debase the experiences of painful pasts. The spectacle of culture produced by the tourist industry is often met with contempt.

Anthropologists and “well-traveled tourists” often regard the likes of “tourist dances” as particularly tacky, according to US scholar Edward M. Bruner. And yet, fellow anthropologist Paulla Ebron argues that heritage tourists may also be pilgrims and their commercial cultural experiences may be intimate and sincere. She notes: “Africa became sacred and commercial, authentic and spectacular.”

The Marina Project is also contested for other reasons. Some fear that mass tourism will have an adverse impact on an area known for its unique ecosystem and biodiversity. Adding to concerns is the development of another gigantic seaside resort nearby, Club Med’s d’Avlékété.

There are already numerous slavery heritage sites in Benin. These range from the European forts in Ouidah to the royal palaces of the kings of Abomey, Porto Novo and Allada.

It’s my view, as an anthropologist, that the latest developments are walking a fine line, balancing education and remembrance with crude commerce.

Teaching slavery in Africa

Slavery and the slave trade remained insufficiently taught in schools. In 1998, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) implemented the Transatlantic Slave Trade education project. Participating countries in West Africa, like Ghana, Senegal and The Gambia, helped address the issue.

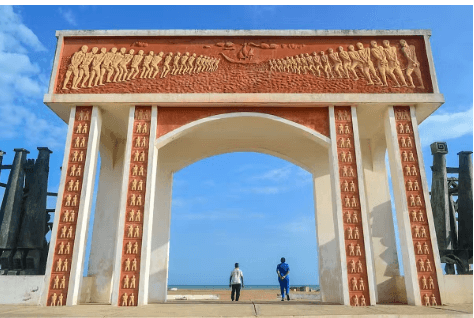

On the beach in Ouidah, the Door of No Return is a concrete and bronze arch with poignant images of shackled bodies of enslaved Africans. It’s one of the city’s most notable landmarks — but only one among hundreds. The road from the slave market to the monumental gate was marked by two dozen sculptures and symbolic stops commemorating the march of the captives.

For example, the Da-Silva Museum in Porto Novo, Benin’s administrative capital, opened in 1998. The private institution offers resources (exhibitions, documents, spaces) for school pupils to learn about slavery. Its founder, Urbain-Karim-Elisio da Silva, is a prominent aguda — part of an Afro-Brazilian community related to slave traders and former slave returnees.

New memorials in a complicated landscape

On my last visit to Ouidah in February 2022, the Door of No Return and museum were undergoing renovations. The sculptures had been removed while the road was rebuilt. The museum is to be reborn as the International Museum for Memory and Slavery.

But the Marina Project, next to the door, is the most spectacular of the new developments. A video clip released by the government lists several of its buildings. Their names — “Afro-Brésilien,” “Bénin,” “Caraïbes” — acknowledge the descendants of enslaved Africans.

The new structures add to an already multi-faceted (and sometimes disputed) treatment of the country’s complicated involvement with the slave trade. Descendants of slave raiders and slave traders live alongside the descendants of enslaved people. Their competing memories and separate interests have led to differing memorial strategies.

Anthropologist C. Ciarcia cites two opposing stances. In Ouidah, where tourism infrastructures are concentrated, forgiveness — through ritual atonement and commemoration — is sought publicly. In Abomey, the former capital of Dahomey and its slave raiders, narratives are less apologetic. For fellow anthropologist Anna Seiderer, the presence of vodun, in particular, has been important for tourists who are eager to imagine and enact their roots.

Slave heritage tourism and its discontents

Slave heritage tourism in Africa caters mainly to the interests of foreign visitors, especially descendants of enslaved Africans in North and South America and the Caribbean region. Several UNESCO world heritage centers curate these legacies for tourists: Gorée island (Senegal), slave castles (Ghana) and Stone Town (Tanzania). To be sure, tourism development was always part of the slave route project, even before UNESCO.

Ouidah’s new developments are featured in the Benin Révélé — a grand development program imagined by president Patrice Talon. According to some detractors, a lot of these projects will become white elephants, used by few.

Another recurring criticism is that new museums, memorials and events are fashioned by foreign experts, rather than local talents. The new sites are designed, built and staged by mostly French or Chinese architects, engineers and curators.

The Marina Project is one of many projects that memorialize Benin’s past. The combining of commercial and memorial goals doesn’t make them less able to teach history or offer intimate processes of remembrance. But the new trend in high-end cultural consumption is seemingly more problematic.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives. The Conversation. This story was written by Dominique Somda.

Related: Germany plans to return looted Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. Will other countries follow suit?