‘It is a legacy’: How British-era ghosts are kept alive in India’s hill towns

Every weekday at 5 p.m., a siren blares through the city of Shimla to signal the end of the workday. It’s a practice that began during the British rule of India. Shimla, a small town nestled in the Himalayas, was their summer capital.

The British would often sojourn to the hills to escape the blistering heat. The northern Indian hill towns — with their breathtaking views and lush, cedar forests — became a favorite haunt of British high society.

After India declared independence in 1947, the hill stations became modern tourist spots that are now thronged by domestic and international travelers alike. But reminders of the British still linger in the hill stations in the form of Gothic lodges, anglicized street names, churches — and ghosts.

“The British have left, but they left their ghosts behind.”

“The British have left, but they left their ghosts behind,” Sumit Raj said with a laugh while strolling along The Ridge, a popular hilltop promenade in Shimla’s city center.

Raj runs a company called Shimla Walks, which conducts heritage walking tours. He is a Shimla native and grew up hearing all kinds of spooky stories.

“One story about an orange seller is very famous,” he said. “Somebody used to sell oranges at night. The moment you [would] ask him the rate of the oranges, he would give you an orange and suddenly you would see it turning into a skull.”

Many of the stories Raj has heard over the years feature Shimla’s colonial-era residents. There’s a headless horseman who rides at night, an Englishman who waits mysteriously beneath different lampposts and parading soldiers who have been seen even in broad daylight.

Shimla’s colonial-era ghosts were first popularized by Rudyard Kipling, the famous author of “The Jungle Book.” In 1888, he published “The Phantom Rickshaw” and other short stories set in Shimla. Kipling called it “a collection of facts that never quite explained themselves.”

In the feature story, a British man’s former lover dies after he leaves her for a younger woman. But soon, he is haunted by visions of his dead ex-girlfriend in a rickshaw. The golden-haired woman’s apparition follows him around Shimla, imploring him to take her back.

“It became so popular that Shimla became famous for ghosts,” Raj said.

Practically all the British-era buildings in the town are rumored to have some paranormal activity or another. Government housing often finds no takers because people fear they may be haunted.

But the ghosts aren’t all necessarily evil. There’s an English nurse who comes to intervene when patients are being neglected, scaring human nurses who are slacking on the job. One British gentleman’s spirit, which supposedly lives in Shimla’s Tunnel 103, is actually believed to have saved some people from being crushed under the train, Raj explained. It’s a kind spirit who chats with passersby, but has never harmed anyone.

Raj knows all of this from hearsay. He has never met the tunnel ghost, or any of Shimla’s other supernatural beings, even though he’s gone looking for them many times.

“When I come to know that something is happening, I try to go and experience it,” he said. “But fortunately, or unfortunately, I have never experienced it.”

Shimla isn’t the only place whose colonial-era residents refuse to be exorcized. Mussoorie, another small town in the Himalayas, is also the setting for many paranormal tales.

“Tourists are seduced by the town’s literary ghosts,” Arup Chatterjee, a professor of English at O.P. Jindal Global University near Delhi, wrote in The Conversation.

“Every once in a while, an ordinary night’s peace is disrupted by the purportedly paranormal interventions of a dead memsahib [a title given to upperclass white women, often used by non-white subjects] such as the spiritualist, Frances Garnett-Orme.”

Garnett-Orme was allegedly poisoned in Mussoorie’s Savoy Hotel in 1911, and her ghost is said to haunt the hotel even to this day. According to Ruskin Bond, author of several short ghost stories based in Mussoorie: “If you live in the Indian hills, it is only a matter of time before you meet a ghost.”

Today, ghost tales of Indian hills are a popular category in Indian literature. Raj considers the stories part of Shimla’s heritage, much like its colonial-era architecture.

“It is a legacy. So, we must preserve it,” Raj said. “It is always going to be part of Shimla.”

But some modern-day Shimla residents are ready to leave the colonial past — including ghosts — behind. Sonal Thakur, 29, grew up hearing the spooky tales, too, but doesn’t think much of them. In fact, she said they may have been part of a larger conspiracy by the colonizers.

“I think the Britishers spread this rumor because they wanted the Indian people [to] fear them,” she said.

She doesn’t want Shimla to be known as the land of ghosts, but rather, as the land of gods, referring to the many Hindu shrines in the region.

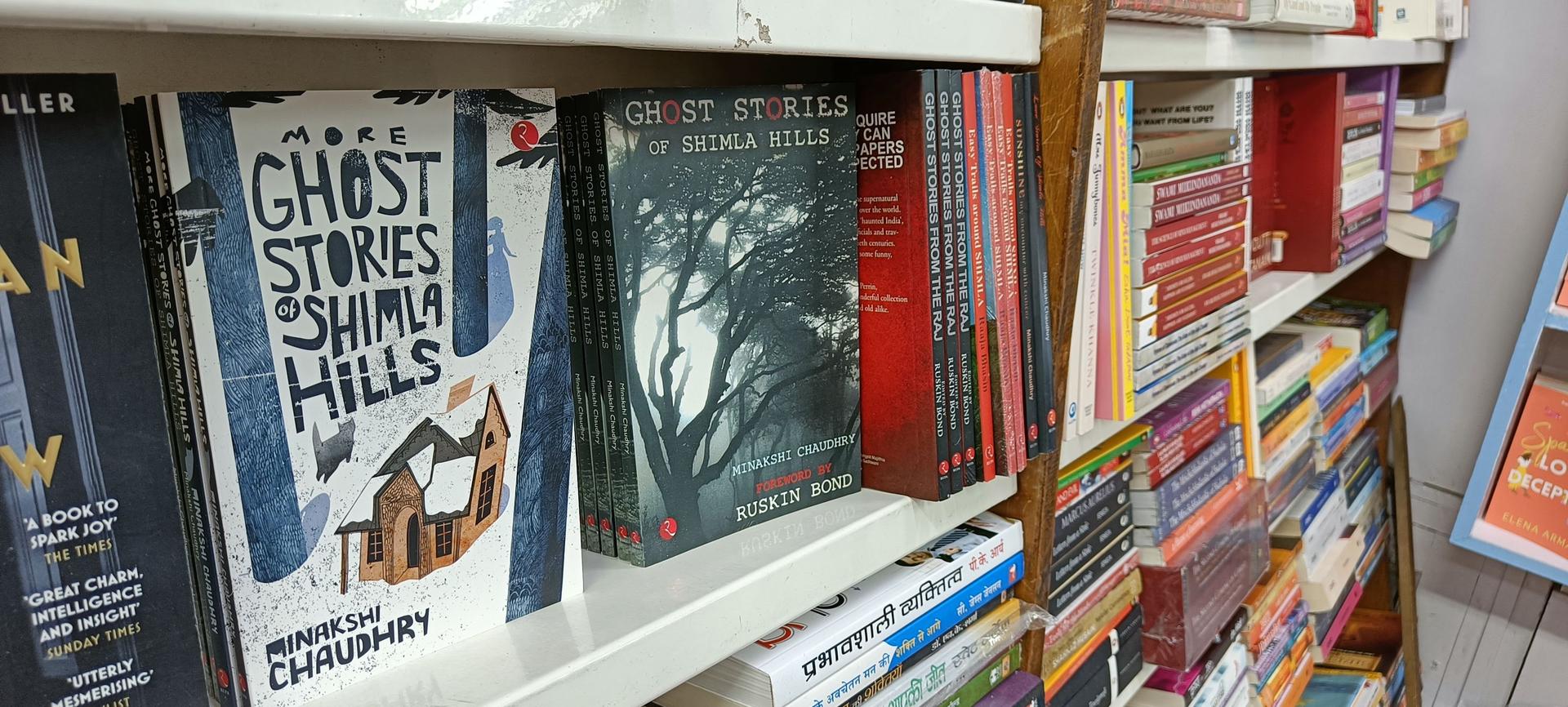

But like gods, ghosts too are a subject of faith, said Minakshi Chaudhry, who has written two books on Shimla’s ghosts. People are often conflicted in their feelings about ghosts and may feel hesitant to talk about them. While she was doing her research, people slammed their doors in her face.

“Supernaturalism is something which is very close to everyone’s heart — you don’t go around basking in its glory or in its evilness,” Chaudhry told The World during an interview at her cottage in Shimla. “

As far as Shimla people are concerned, when I was working on the first book, they were very skeptical. They were very reluctant to tell me the stories. However, once the book was published, I met hundreds of them who told me ‘you didn’t cover our ghosts,’ and they were not joking, they were serious.”

Chaudhry has documented dozens of unexplained sightings featuring all kinds of paranormal beings.

“I found that, apart from the English ghosts, we have a lot of Indian chudails [mythical creatures resembling a woman] and rakshas [demons] out here,” she said.

There’s an Indian ghost that loves to imitate humans. And an apparition in a sari who glides alongside cars and guides them off a cliff. The stories are hugely popular — Chaudhry’s first book is in its 26th impression and the second is in its 17th. So, what explains this enduring craze for scary stories?

“For thousands of generations, everyone has been attracted by the unknown.”

“For thousands of generations, everyone has been attracted by the unknown,” Chaudhry said. “Whether it’s Europe, Latin America or in Asian countries, everyone is interested and excited about the unknown. If this unknown was not here, life [would] be so boring. It gives you that zing.”

Ghost stories, she said, in their own peculiar way, enrich our lives.

Related: Haunted India: A new ghost compendium features 700 creatures from A to Z

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?