Humanitarian rescue boat stranded in Spanish port over ‘administrative persecution,’ NGO says

Of all the humanitarian vessels rescuing migrants in the Mediterranean Sea, where at least a thousand people have died so far this year, few, if any, are better prepared to save lives than the Open Arms Uno.

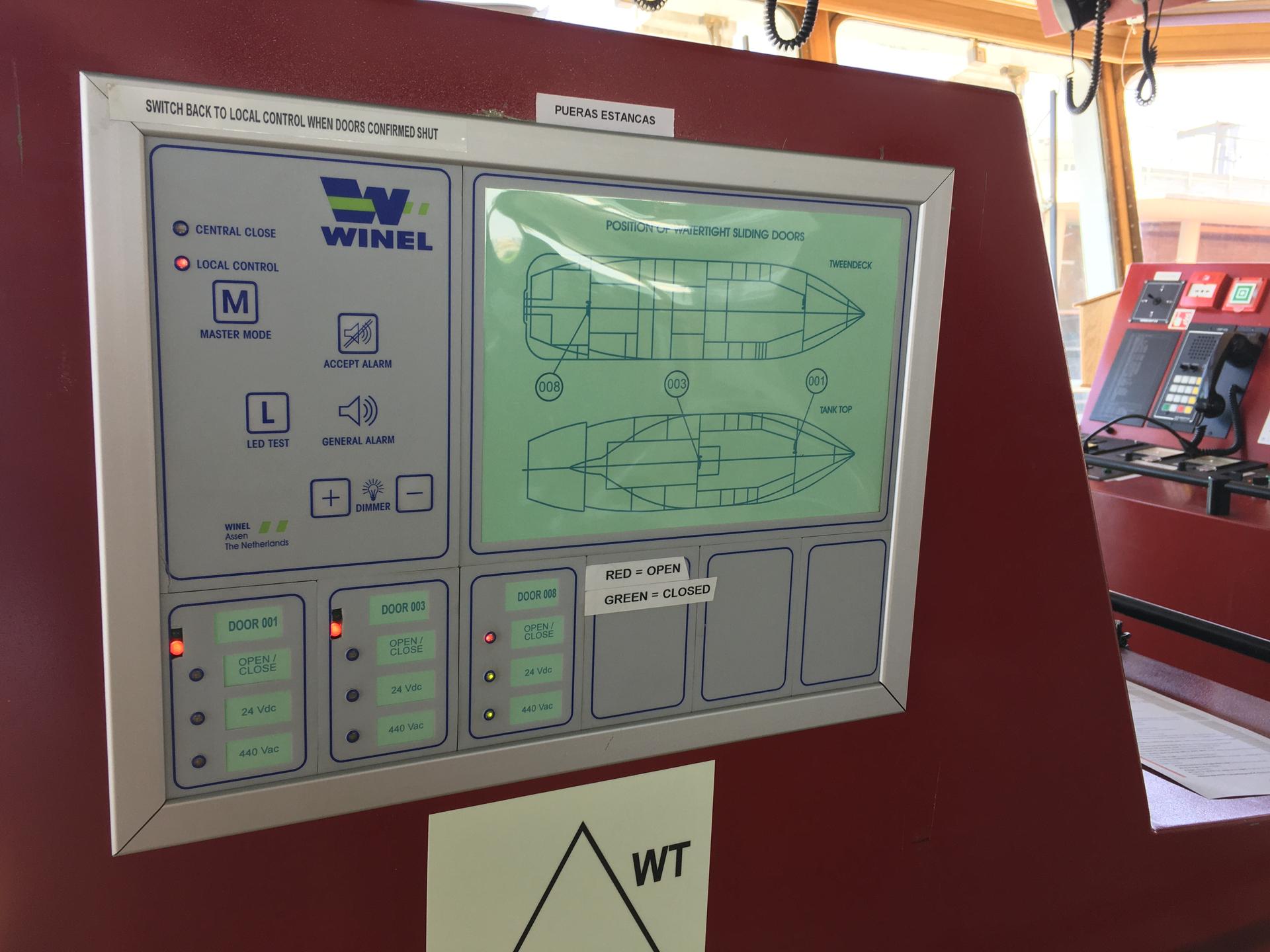

The boat, recently acquired by the Barcelona-based, nongovernmental organization, Open Arms, has a hospital, 26 hospital beds, four, semirigid inflatable boats, and a landing strip for a helicopter. It’s about 216 feet long and 49 feet wide; in case of an emergency, there’s room for over 1,000 people.

“I would dare to say that it’s the best mass-rescue ship in the Mediterranean,” said Oscar Camps, a lifeguard and founder of Open Arms.

But there’s a caveat: The Open Arms Uno has yet to begin rescuing people.

The boat first arrived on May 22 to the port of Barcelona, where it was greeted with a public celebration; two months on, the vessel is still pending permission to begin operations.

Camps blames Spanish authorities for the delay and accuses them of “administrative persecution.”

“They asked us all kinds of things, and some were just absurd,” he said.

On paper, he said, the certification process in Spain should have been straightforward: Before a philanthropist loaned it to the NGO last November, the boat was operating in the Northern Sea under the flag of Ireland, a fellow European Union country.

But the ship was not registered as a rescue boat in Ireland, but one providing support to oil rigs, the maritime captain of Barcelona, Javier Valencia, explained in a written response to The World

That meant the ship then had to be adapted to meet new requirements.

For starters the boat was required to increase the minimum safe manning from 9 to 12 people over fatigue concerns, and all documents had to be translated from English to Spanish to ensure effective communication among crew members.

Valencia said that the ship was only registered in Spain on June 2, so the certification process could not start until then, but it’s now nearly complete.

Bureaucracy

Itamar Mann, a professor of international law focusing on migration at the University of Haifa, Israel, said it’s hard to prove whether Spain is intentionally delaying the certification of the Open Arms Uno.

What’s certain, he said, is that European governments have for years used maritime travel regulations to hamper the work of sea rescue NGOs.

Charities have been vocal in denouncing such practices, with Doctors Without Borders claiming that ships are routinely held hostage by unrealistic standards, and inspections misused in “a sustained campaign to criminalise saving lives.”

“All these administrative, and you might say, bureaucratic, requirements are entry points for governments to try to control these acts of solidarity that do not always fit their general immigration policies,” Mann said.

‘From heroes to villains’

The number of refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean peaked in 2015, with more than a million reaching Europe.

That year, Camps founded Open Arms, and he recalled that collaboration was common between maritime authorities and sea rescue organizations.

But that changed amid the political backlash caused by the rise of anti-immigration movements.

“We went from being heroes to villains, from working closely with Italy’s Coast Guard to being portrayed as criminals by the media,” Camps said.

A tipping point, he said, came in 2018, with the rise of the far-right League in the Italian election, which led to party leader Matteo Salvini serving as deputy prime minister and minister of the interior.

In 2019, Salvini delivered on his “closed ports” policy by denying a safe harbor to one of Open Arms’ vessels. The boat was stranded for 19 days off the island of Lampedusa — with more than 100 rescued migrants on board.

With Salvini facing a trial on charges of kidnapping that could carry a prison sentence of up to 15 years, Camps said that justice is proving them right.

Similar standoffs are likely to come, Camps said, and added that the Open Arms Uno will be of utmost value since its facilities allow for lengthy expeditions without compromising the safety on board.

Missing migrants

In 2020, the EU shut down Operation Sophia, its former naval mission in the Central Mediterranean to combat people-smuggling and to prevent deaths at sea, following concerns by some member states that the presence of rescue vessels there was a pull factor leading to more migrants venturing across the sea — a notion debunked by scientific studies and EU officials.

Mann called such an idea a “figment of the imagination” and a “recipe for catastrophe,” and added that denying migrants safe routes leads to them taking more dangerous ones.

At least 24,386 people have either died or gone missing in the Mediterranean since 2014, according to the Missing Migrants Project by the International Organization for Migration.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?