Rodney Montreuil, a high school math teacher, is a busy guy. After work, and even during spring break, he helps Haitian families get settled and begin their lives anew in Phoenix.

“I’m going to visit a couple of clients today,” he said. “The first is a couple, they arrived in October.” They were among thousands of Haitians gathered under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas, last year, many seeking asylum.

Haitians have faced one disaster after the next in recent months: A 7.2 magnitude earthquake hit just outside Port-au-Prince in August and Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated the month before.

“We are living in hell in Haiti,” Montreuil said.

Related: Pressure mounts for Biden to end Trump-era Title 42 that shuts out migrants seeking asylum

Montreuil is from Haiti, too, but he’s spent two decades in Phoenix. Every day, he helps newly arrived Haitians with everything from money transfers to job searches. His phone rings constantly.

Over the past couple of years, thousands seeking asylum in the US have been turned back to home under Title 42, a pandemic-era protocol that allows border officers to turn away migrants and asylum-seekers on public health grounds.

This past Sunday marked two years since it was put in place by the Trump administration.

The Biden administration officially ended the policy for unaccompanied children earlier this month, but it remains in place for both families and adults traveling alone. Now, the administration faces mounting pressure to repeal the protocol altogether, especially for Haitians.

More than 20,000 have been removed from the US, largely under the protocol, during President Joe Biden’s tenure alone, according to the advocacy group Witness at the Border, which tracks removal flights.

Montreuil said that many people are being sent back to a country they haven’t been to in years. As a young man in Port-au-Prince, he started as an intern with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and eventually landed in a position in the National Defense Ministry. He left in the early ’90s after his mom told him that she worried his job would get him killed.

“My mother used to say, ‘Man, I would like to die before I got a call from the police that they found a body in the streets,’ that sounded so powerful … she used to say it all the time,” he said.

Related: Russians and Ukrainians attempt to flee to the US through Mexico

A few years ago, he watched from Phoenix as more turmoil ripped through his country. He knew many more Haitians would soon make their way to the US.

“I woke up one day, and I’m like, does anybody care … care about anything bad that was happening to our Haitian brothers and sisters?”

“I woke up one day, and I’m like, does anybody care … care about anything bad that was happening to our Haitian brothers and sisters?” he said.

In 2016, he started an organization called the Haitian American Center for Social Economic Development run by all volunteers. It’s about helping people arrive and also about building up the Haitian community in Arizona.

Through his organization, Montreuil meets with newcomers like Dieula Sainvil, a young mother staying at a shelter in west Phoenix.

Sainvil is 27, with tight black curls fastened into a bun with a sparkly barrette. Her tiny daughter, who was born in Phoenix just last month, was dozing off in a baby carrier and she cooked on the stovetop at the shelter. Montreuil translated for her.

She said that she decided to leave Haiti after her father was killed by gang members in 2019.

“I am a daughter, and most of the time, sons have a tendency to seek revenge for their relatives, but I didn’t see it that way,” she said in Creole. “I immediately envisioned getting out of the country.”

Sainvil said she went to Brazil, then Chile. She and her husband reached the US-Mexico border last December.

Related: ‘Haitians deserve a chance to determine their own future,’ former US envoy says

Her husband has family in Indianapolis, and they’d planned to head there. But Sainvil said that they got separated in immigration detention in Texas. She was released earlier this year before giving birth in February. Her husband was released a couple of days ago but she’s not sure yet if he’ll be sent back to Haiti, or if she will.

“Life is pretty tough for my family in Haiti,” she said. “Most of them take a chance and venture into the Dominican Republic to look for jobs, and sometimes, they face serious difficulties or maybe death.”

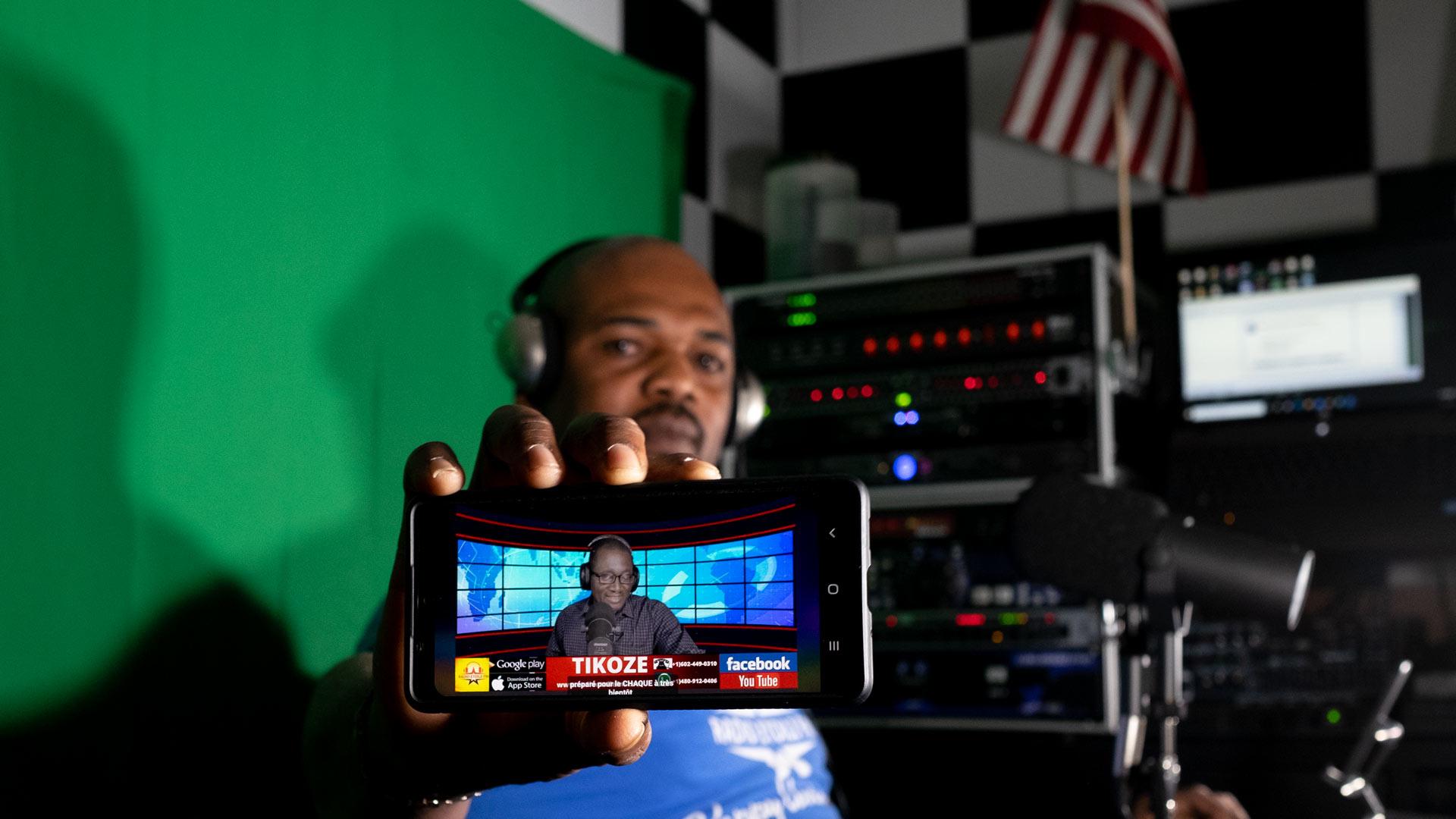

Montreuil tries to address questions like that every week on his live radio program, Tikoze, which means “let’s have a chat” in Creole.

“This radio show informs, educates and entertains the Haitian community, wherever you are,” he said.

He talks about everything from immigration issues to how to file taxes in the US — and he shares some hard truths about what to expect at the border.

“The truth of the matter is that it’s no secret that Black people have been treated differently than any other ethnicities,” he said. “We happen to be Haitians and Black, so, that’s a fact.”

Still, Montreuil said that he wants people to know what’s possible. In fact, this internet radio station is run by another Haitian named Josue Philistin. They broadcast out of a living room in a suburb outside Phoenix and have listeners all over the world.

“Brazil, Chile, Haiti,” Philistin said in Creole. “Basically, anywhere where there’s internet, people can listen.”

Philistin was the first person Montreuil sponsored to get out of immigration detention in Eloy, Arizona back in 2016. He lived with Montreuil for a while in Phoenix and won his asylum case a few years ago. He’s getting ready to buy his house now, not far from where he spent more than seven months detained.

“Josue symbolizes what I hope my job significance will be. I mean Josue is my hero, seriously,” Montreuil said.

Montreuil said that he knows he can’t solve all the issues Haitians are facing now. But he hopes he can offer a bit of clarity, and a helping hand, whether in person, or on the air.

A version of this story originally appeared in Fronteras.