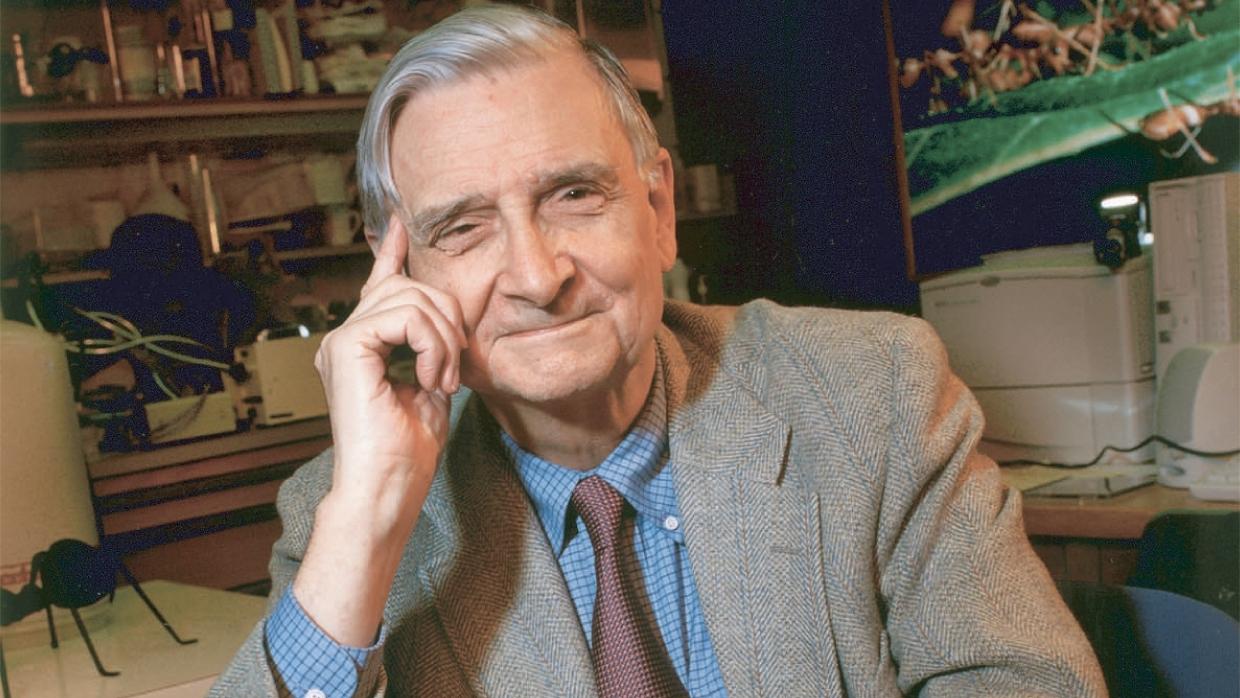

E.O Wilson, a Harvard professor and a pioneer in the field of conservation biology, died on Dec. 26, 2021.

Wilson won two Pulitzer prizes for his nonfiction books and inspired generations of students and colleagues with his infectious love of the ants he studied and his bold ideas about how to stem species extinction.

Wilson laid out his call to preserve the Earth’s biodiversity in his book, “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.”

“I like to call it, ‘one Earth, one experiment.’ We’ve only got one shot at this. Let’s be careful.”

“I like to call it, ‘one Earth, one experiment,’” Wilson once said. “We’ve only got one shot at this. Let’s be careful.”

In a 2017 interview with Living on Earth from PRX, Wilson said:

“What we need to do is try for a moonshot, and the moonshot is to set aside half the surface of the land and half the surface of the sea as a reserve, a reserve that doesn’t exclude people, by any means — Indigenous people are, in fact, encouraged to enjoy them and continue their way of life. But, if we could give half of the Earth primarily to the millions of other species that inhabit the Earth with us, then we would be able to save about 80 to 90% of the species, bring the extinction level down to what it was before the coming of humanity. That would be a successful moonshot.”

Wilson’s bold plan has inspired roughly 70 countries to commit to protecting at least 30% of their land and oceans by 2030, as a first step.

Related: A plan to save more than 80 percent of Earth’s species

Jane Lubchenco, a marine ecologist and Oregon State University distinguished professor who is currently serving as deputy director for climate and environment in the White House, worked with E.O. Wilson for over five decades. She says he made so many important contributions to the field of conservation biology that it’s hard to know where to start.

“Obviously, ants were his passion and his lifelong love throughout his career, but he was able to build on those observations and create really innovative breakthroughs in multiple areas,” Lubchenco says.

Wilson discovered how ants communicate with one another via pheromones and developed the theory of island biogeography, which focuses on identifying the guiding principles behind how best to protect the species found on islands and fragments of habitat. The theory was created both mathematically, with Robert MacArthur, and then tested experimentally with one of Wilson’s graduate students, Dan Simberloff.

“[Wilson’s] theory of island biogeography has really formed the foundation of modern conservation biology. It enabled people to think about, where do we want conservation parcels to be? How big should they be? How should they be connected to one another?”

“That theory of island biogeography has really formed the foundation of modern conservation biology,” Lubchenco says. “It enabled people to think about — where do we want conservation parcels to be? How big should they be? How should they be connected to one another?”

Wilson also created new ideas about how people connect to nature and how nature influences people, Lubchenco says. He created the concept of biophilia, which suggests that humans have an innate connection to nature.

All of Wilson’s ideas were “grounded in very detailed, keen observations, but result[ed]in some grand theories and grand vision,” she says.

Wilson was a gifted teacher, as well, Lubchencko notes.

“He was so adept at being able to explain something, but to do it in a way that would then trigger new thoughts on the part of the person he was interacting with. He would stimulate ideas and encourage others to sort of take them on to the next level and make them relevant to their lives.”

In the 1970s, when Lubchenco was a graduate student and then an assistant professor at Harvard, there was a lot of tension in the biology department, she says. Molecular biology was on the rise and many of the field’s leaders — James Watson, in particular — “were very arrogant about ecology, evolution, systematics, and really dismissed that field as just a bunch of stamp collectors.”

For Wilson, being dismissed and marginalized “was very powerful motivation to show that, in fact, the science of ecology, [and] of evolution, were actually legitimate in their own right, and not yesterday’s science but tomorrow’s science,” Lubchenco says.

Harvard didn’t treat Wilson particularly well, either. The university didn’t want to give him tenure and “stuck him” over in the museum with his ants. But through the years, he kept his office in the museum and never lost his excitement and enthusiasm for his ants and the big ideas they inspired.

Related: Why a famous biologist wants to eradicate killer mosquitoes

In his lab with his students, Wilson would “just light up and get so excited,” Lubchenco says. His “palpable excitement…provided a really powerful antidote to a lot of the tension that was in the department more broadly.”

Wilson’s notion of “half-Earth” may turn out to be his most influential idea.

“Ed was a big thinker, and he didn’t do things halfway. But when he did them, they were solidly grounded in evidence, in good science.”

“Ed was a big thinker, and he didn’t do things halfway,” Lubchenco says. “But when he did them, they were solidly grounded in evidence, in good science. Through the years and his extensive travels, he really became quite concerned about the sixth mass extinction event of biodiversity, the first one in the whole history of Earth that was being caused by people. He saw firsthand the numbers, but also the devastation in many different habitats, and he became very, very concerned about the future of the planet, the future of people, in part because we were losing so many species.”

These experiences led Wilson to develop the concept of protecting half of the planet for nature, an idea that many dismissed as completely impossible because at the time only about 3% of the ocean and 17% of the land on Earth was fully protected.

“The idea of 50% was just mind boggling, and still is to many,” Lubchenco says. “Nonetheless, he became a staunch champion, very eloquent in his speaking and his writing, focusing on the importance of saving nature, not only for its own sake, but also for our sake. And that concept has gained a lot of support from colleagues and others. The fact that many countries are focused on 30% is quite remarkable, actually.”

It remains to be seen how effective that protection is, Lubchenco cautions.

“Something that is fully protected is really, really different from something that’s only lightly or marginally protected,” she explains. “So, the devil is in the details, with respect to the execution. Nonetheless, his idea was a bold challenge and an inspiration to many people.”

This article is based on an interview by Steve Curwood that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.