Russians in the UK face hate speech, verbal abuse as war rages in Ukraine

When Polina Skovoroda-Shepherd organized a peace concert last Saturday to raise money for Ukrainian refugees in Brighton and Hove, on the southern coast of England, she feared the event would be a target for anti-Russian hate.

Skovoroda-Shepherd, who was born in Siberia, is now a choir leader of two Russian choirs in the United Kingdom that came together for the peace concert. The singers come from several European countries including Russia and Ukraine. But some local Russian community members in Brighton who helped organize the event were too nervous to attend, Skovoroda-Shepherd said.

Related: Ukrainian refugees trying to get to the UK are stuck in the French port city of Calais

“[Some Russian community members] told me that they’re afraid to come to the concert themselves because they have been getting violent messages and phone calls.”

“They told me that they’re afraid to come to the concert themselves because they have been getting violent messages and phone calls,” Skovoroda-Shepherd said.

On the heels of the British government’s new sanctions on 386 Russian lawmakers, including asset freezes and travel bans, incidents of anti-Russian sentiment have been recorded in the UK. Verbal attacks and hate speech has also been lobbed at Russians across Europe, including the Czech Republic, Germany, Portugal and Norway.

Related: Ukrainian, Russian tourists stranded abroad

In Prague, a university professor wrote on social media that he would no longer teach any Russian students. The post was later deleted. In Bietigheim, in southwestern Germany, a restaurant put a statement on its website saying customers with Russian passports would not be served. In Wales, Cardiff Philharmonic dropped Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, a Russian composer, from its repertoire for an upcoming concert.

Skovoroda-Shepherd, who featured music from Tchaikovsky in her concert on Saturday, said she was dismayed by the move.

“I feel that it’s destructive. I feel it’s negative. I would urge people to see the beauty of the music despite some current dictators in that country,” she said.

Related: Many Ukrainians face a future of lasting psychological wounds from the Russian invasion

Skovoroda-Shepherd points to “cancel culture” — the contemporary trend of ostracizing a person or concept en masse through social media — to explain recent actions taken against Russian composers and artists, both living and deceased.

The Munich Philharmonic Orchestra fired its lead Russian conductor Valery Gergiev earlier this month after he failed to speak out against the war in Ukraine. Skovoroda-Shepherd argued that Gergiev may have been reluctant to speak out for fear of repercussions for his family.

The British-based choir leader said she doesn’t feel nervous about condemning Putin’s actions because she’s not a household name in Russia.

But some well-known Russians are making their feelings known.

Moscow-born pianist Petr Limonov, who lives in London, conducted an orchestra of 200 musicians in Trafalgar Square last weekend to protest the war. The performers played a series of Ukrainian songs including the Ukrainian national anthem in a version arranged by Keith Terrett.

Many of the musicians played through tears, Limonov said.

“I’ve never seen so many musicians crying as they were playing and I was conducting them. It was just incredibly moving. I cannot describe it,” she said.

Limonov said he has experienced no animosity in London for being Russian and disagrees with those who say they are nervous to speak up out of fear of retaliation.

“The time for us Russians has come to just rise up and say ‘no’ and to stop thinking about the consequences of, you know, being locked up, or some sponsorship deal being canceled.”

“The time for us Russians has come to just rise up and say ‘no’ and to stop thinking about the consequences of, you know, being locked up, or some sponsorship deal being canceled,” he said.

Limonov said his cousin in Moscow has been protesting on the streets in Russia. His aunt called him in tears, terrified that the cousin would be arrested and jailed.

When he texted his own mom in Russia about the impromptu concert supporting Ukraine in London’s Trafalgar Square, she messaged back to say his family supported him “unconditionally.”

Many airlines have canceled flights to Moscow because of the invasion. Limonov said he is unlikely to return home anytime soon. He said he’s heard about Russian authorities stopping and searching travelers’ phones for text messages that hint at opposition to Putin or the war.

“I will not perform in Russia until we change our political system drastically,” he said.

Related: Ukrainians abroad return to defend their homeland

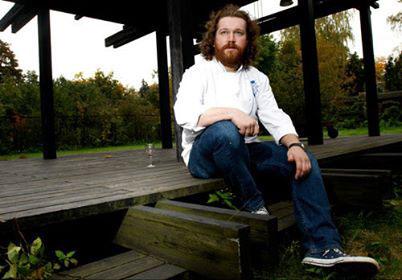

Celebrated Russian chef Alexei Zimin may soon find himself unwelcome in his home country. He runs a well-known Russian restaurant called Zima in London’s Soho area and is also famous back home for his cookbooks and two restaurants, one in Moscow, and the other in Penza, in western Russia.

A former TV presenter, Zimin last week began posting videos of himself on Instagram singing songs by a dissident Russian poet.

“Stop the war, get the troops out and bring our soldiers home,” he wrote in Russian.

Within a few days, he said, he lost 3,000 followers.

At his London restaurant, Zimin is also receiving abuse — just for being Russian. Offensive messages have been left on the restaurant’s voicemail calling him “Putin’s Russian” and threatening to burn down his establishment.

But Zimin said he’s not bothered by the trolling.

About 10% of the restaurant’s earnings is now going to support the humanitarian effort in Ukraine. Zimin knows speaking out against the war could hurt bookings at his two restaurants back in Russia. But he said he is prepared to accept that.

“If I lose, I lose. If you need to lose two restaurants for this then, yes, let’s do it. Let’s do without two restaurants.”

“If I lose, I lose. If you need to lose two restaurants for this then, yes, let’s do it. Let’s do without two restaurants.”

Skovoroda-Shepherd, the performer and choir leader in Brighton, said Saturday’s concert went off without incident in front of a full house.

The only abuse she has received to date has been from strangers on social media. But a number of her friends’ children have been bullied in school — verbally and physically — in the last few weeks for being Russian.

On a recent phone call home, her mother suggested that if “Russophobia” becomes too much in Britain, she could always move back to Russia.

Skovoroda-Shepherd laughed and said she doesn’t think that’s a good idea, not for her — and certainly not right now.