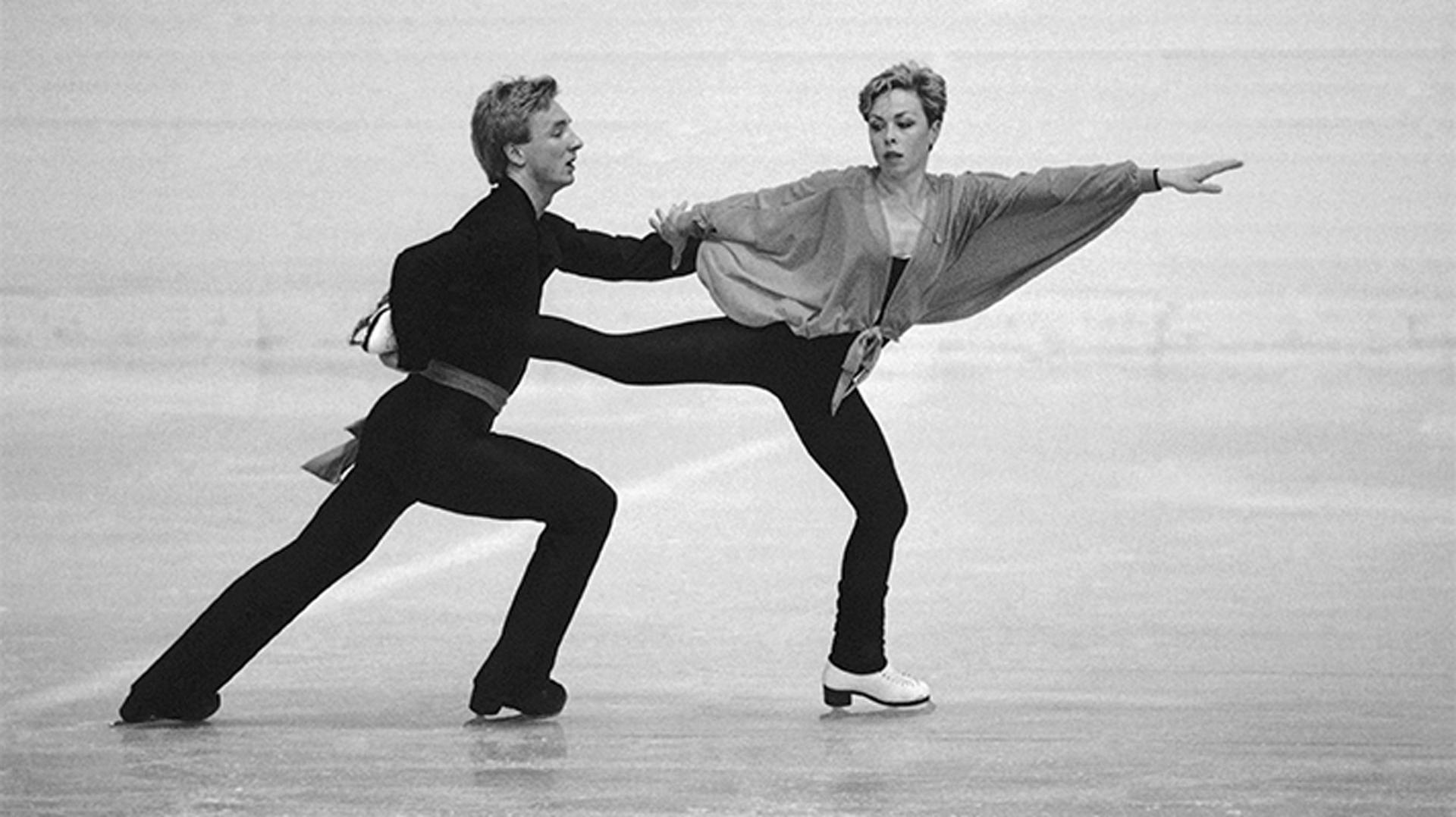

In February of 1984, at an ice rink in Sarajevo, English pair Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean made history. The event is still among the most-watched events broadcast on British television, and their performance earned them near-perfect scores from all 12 judges, plus a gold medal. Their ice dancing routine remains a gold standard for artistry, set to Maurice Ravel’s less universally adored symphonic work Boléro.

The music would not be reused in any figure skating or ice dancing event for over a decade. But at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Boléro would score no less than three routines: Kamila Valieva, Shoma Uno, and Boyang Jin.

Torvill and Dean’s use of Bolérorequired quite a bit of work off the ice. In order to find the requisite artistic skills to express the piece, they sought help from actor Michael Crawford, best known as the title character in Broadway’s The Phantom of the Opera.

Plus the piece itself is 18 minutes long, and their routine needed to be four minutes. It’s not a piece where one can fade in or out mid-phrase given the repetition, which meant that the arranger could only pull it down to 4 minutes and 18 seconds. Finding a technicality in the rule book which stated that the clock only started when the skating started, the pair began the routine kneeling — their mirrored choreography creating an intimacy and tension that rivaled the repeated snare drum line in Ravel’s music.

The Winter Olympics only began to be held in 1924, with the first occurrence in Chamonix, France. Paris also held the Summer Games that same year. Ravel was a judge of the music competition, which was part of the many awards for the arts which were included in the events. And even though Ravel wrote Bolérojust four years later as a commission for ballerina Ida Rubenstein, it’s hard to imagine he ever predicted it would become a figure skating icon, especially since it was not exactly well received.

While it was staged with the setting of a tavern in Spain, Ravel actually conceived of the piece taking place in a factory. The composer had always been interested in mechanics: His father was a civil engineer who worked in manufacturing. This, combined with the Spanish songs his mother sang to him during a childhood near the France-Spain border, does seem to lead to the piece’s character. But the repetition and slow, contained growth makes it unique and surprising at first listen. In 2011, historian Michael Lanford suggested in The Cambridge Quarterly a similarity to Edgar Allen Poe’s Philosophy of Composition, noting the repetition of “nevermore” in Poe’s “The Raven.”

Ravel himself downplayed any groundbreaking and seemed bemused by the work’s eventual explosion of success. In the London Daily Telegraph he called it “an experiment in a very special and limited direction,” and rejected the idea that it was for any higher purpose or even approached “virtuosity.”

“I have carried out exactly what I intended, and it is for the listeners to take it or leave it,” Ravel said in 1931.

If Ravel had truly wanted to evoke Spain, he could have. He could have written a flamenco, which he originally planned, or made it a work for guitar. And he certainly could have repeated the opening rhythm, which runs throughout, on castanets rather than the snare drum — though the looming drum does remind one of the military, and that the composer was not far removed from his traumatic time as a servicemember in World War I.

Likewise, none of the performances on ice truly match the composer’s intended setting — not that figure skating generally does with classical music. Kamila Valieva has described herself as playing the role of a snake in her routine.

And, of course, Torvill and Dean’s love story-themed routine is not at all in a factory. And the pair has since said that if the routine was in competition today, it would not be considered technically challenging enough to make it to the Olympics.

But with all of the required skills, blades and even the Zamboni, one could imagine the mechanically minded Ravel enjoying the events nonetheless.

This article by Colleen Phelps was originally posted by WUOL on Februray 3, 2022.

We rely on support from listeners and readers like you to keep our stories free and accessible to all. Monthly gifts are particularly meaningful because they help us plan ahead and concentrate on the stories that matter. Will you consider donating $10/month, so we can continue bringing you The World? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!