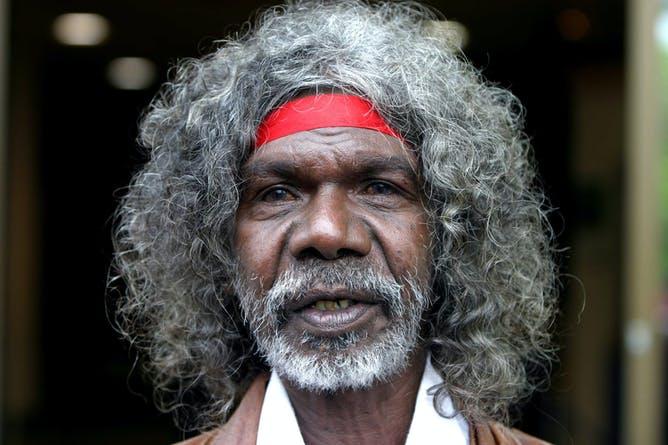

David Dalaithngu shaped Australian cinema — and paved the way for Indigenous actors in the industry

David Dalaithngu

Editor’s note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article includes names and images of people who have died.

I opened #Blackfulla Twitter to find my feed awash with tributes to the life of David Dalaithngu and a deep shared sadness for his passing. As I scrolled, I witnessed a wave of grief and mourning — but also a commemoration of his life and the absolute joy his performances brought.

A member of the Mandjalpingu clan, Dalaithngu was raised on Country in Ramingining Arnhem Land. For many, he was the first Indigenous person we saw on the television or big screen.

To lose him, at only 68 years old, we are reminded how fragile our existence is and how short our lives can be as Indigenous people.

A rich and varied career

Growing up in the 1970s, seeing Indigenous people on the television was rare. I remember the first time I saw Dalaithngu in the film “Walkabout” (1971). The storyline was indicative of the era, and Dalaithngu’s name was misspelled in the credits.

Regardless, his performance was brilliant.

He next played Billy in “Mad Dog Morgan” (1976) and Fingerbone Bill in “Storm Boy” (1976). He was lauded by his Storm Boy co-stars for his ability to perform as if there were no cameras at all. It would be fair to say for many non-Indigenous people during this era, in Australia and internationally, their only exposure to Indigenous culture was through his performances.

In 1977, he starred in “The Last Wave.” A sci-fi drama drawing on mysticism and the dichotomy of urban versus “tribal” identities, it is not a film without problems. But it sparked for me a love of sci-fi I still have today.

In 1986, Dalaithngu starred in “Crocodile Dundee” showing his comedy chops playing alongside Paul Hogan.

His sense of humor was second to none. He often mocked the stereotypes about who we are or who we are imagined to be by white folk.

His performance in “Crocodile Dundee” secured him as a household name across Australia, and, in 1987, he was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to the arts.

A political actor

As Dalaithngu matured, so too did the Australian film industry. He increasingly took on weighty and political roles.

In 2002, he featured in “Mimi,” from the then little-known director Warwick Thornton, poking fun at white art collectors who purchase Indigenous art for its investment potential.

Also in 2002, he starred in Phillip Noyce’s “Rabbit Proof-Fence” and, in his first collaboration with Rolf de Heer, “The Tracker,” for which Dalaithngu won multiple acting awards.

Later, he starred in notable films including “The Proposition” (2005), “Ten Canoes” (2006) and “Charlie’s Country” (2014).

“Charlie’s Country,” which Dalaithngu wrote with de Heer, captures the complexities of living in a settler society and the often violent and discriminatory policies and practices Indigenous people face here.

Set in Dalaithngu’s own Country in Ramingining, in one scene, Charlie and his bestie “Black Pete” (Peter Djigirr) kill a wild buffalo to eat.

They live without adequate finances to buy food from shops. This is a very real situation for many Indigenous communities in Australia.

The local policeman confiscates Charlie’s gun: it is not registered; he doesn’t have a license for hunting on his own Country. Charlie, who describes himself as a hunter, then makes himself a spear. The police also confiscate the spear, claiming it is a “dangerous weapon.”

For this performance, Dalaithngu won one of the world’s most prestigious acting awards, the Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard for Best Actor.

A true leader

Dalaithngu paved the way for Indigenous actors in the industry, and was unforgettable. He was an actor who could not be constrained. Your eye was drawn to him in every role he took on.

In 2019, in recognition of his contributions as an actor, and to the wider Indigenous screen industry, he was awarded a NAIDOC Lifetime Achievement Award.

Sadly, he was too sick to attend so he recorded a message for us all. He said, “Never forget me. While I am here, I will never forget you.”

Although incredibly sick, Dalaithngu wanted to make one more film, and he did. The documentary, “My name is G” (2020), is an intimate story of his own life.

He reflects on the end of his life and tells us “my spirit will return back to my Country.” So it has.

From all of us mob, Vale Uncle.![]()

Author Bronwyn Carlson is a professor of Indigenous studies and director of the Centre for Global Indigenous Futures at Macquarie University. This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.