In France, intensive crash courses for immigrants on French values leave many feeling like outsiders

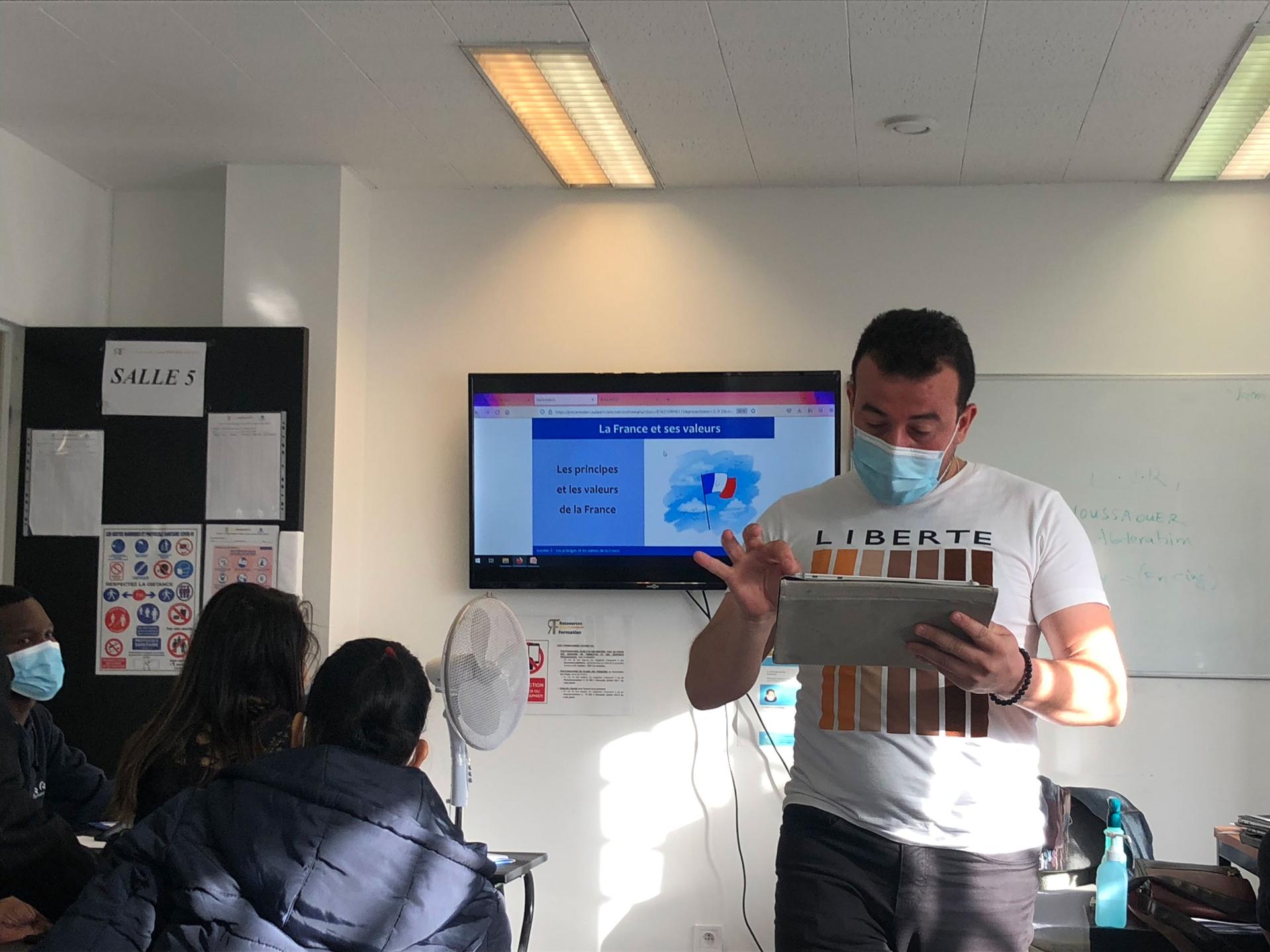

At 9 a.m. on a weekday, a group of people gathers in a tiny classroom to face the second day of an intensive four-day crash course on how to live life à la francaise — the French way.

Related: French society confronts deadly religious tensions

Iconic French symbols line classroom walls, including a photo of the Marianne statue, the ultimate symbol of the French revolution, as well as lyrics to the country’s national anthem, “La Marseillaise.”

As new residents in France, students are required to take classes to help them learn what’s considered to be essential French values. They also learn about social support systems and what it means to participate in French society.

Related: French citizens demand police reform to address systemic racism

Instructor Abderahim Moussaouer takes attendance and gets straight to business.

“What are the values of the French republic?” Moussaouer asked a young man from Sri Lanka.

“Liberty, equality … and maternity?” the man responded, unsure of the last point.

Moussaouer let out a laugh.

“It’s kind of the same pronunciation — but not quite.”

After some encouragement, the man slowly let out the correct answer.

“Fra … fraternity!” or brotherhood.

“Voila!” Moussaouer replied.

Everyone in this group has already signed what’s called the contrat d’integration republican — the contract promising to uphold French republican values. Now they’re learning how to apply them.

“The goal is to provide students with concrete knowledge on how things work in French society.”

“The goal is to provide students with concrete knowledge on how things work in French society,” said Samia Khelifi, a director at the Office for Immigration and Integration (OFII), the government agency that runs these trainings, which are mandatory for most foreign nationals looking to stay in France long term.

They cover lessons on concepts such as gender equality and the importance of respecting laicité, France’s strict form of secularism.

But learning about French values is only one aspect of the training.

Students are also taught how to navigate France’s complex centralized administration system — from accessing health care to employment and social housing.

Launched in 2007 by then-President Nicolas Sarkozy, close to 80,000 people have participated in these trainings in 2020 alone.

Moussaouer describes himself as an ideal model for France’s integration system. He came to France nine years ago from Algeria and is now a French citizen.

Related: Is France ‘sleepwalking’ into voting for the far-right?

“You can imagine all the opportunities that can be found here in France,” Moussaouer said. “For work, for a better social life … everything that encompasses democracy and freedom.”

For years, people have debated France’s integration model of assimilation. That’s different from countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, which tend toward a multicultural approach.

Related: France’s top elite school closes in an attempt to find diversity

With the French presidential elections slated for next spring, immigration and integration have once again become hot-button topics.

Many on the far-right argue that France isn’t doing enough to integrate new arrivals on French soil — particularly, they say, Muslims.

Related: French generals’ letter warning civil war prompts political response

Others say these mandatory classes demonstrate how the French still struggle to define integration without creating an “us vs. them” mentality — leaving many immigrants feeling like permanent outsiders.

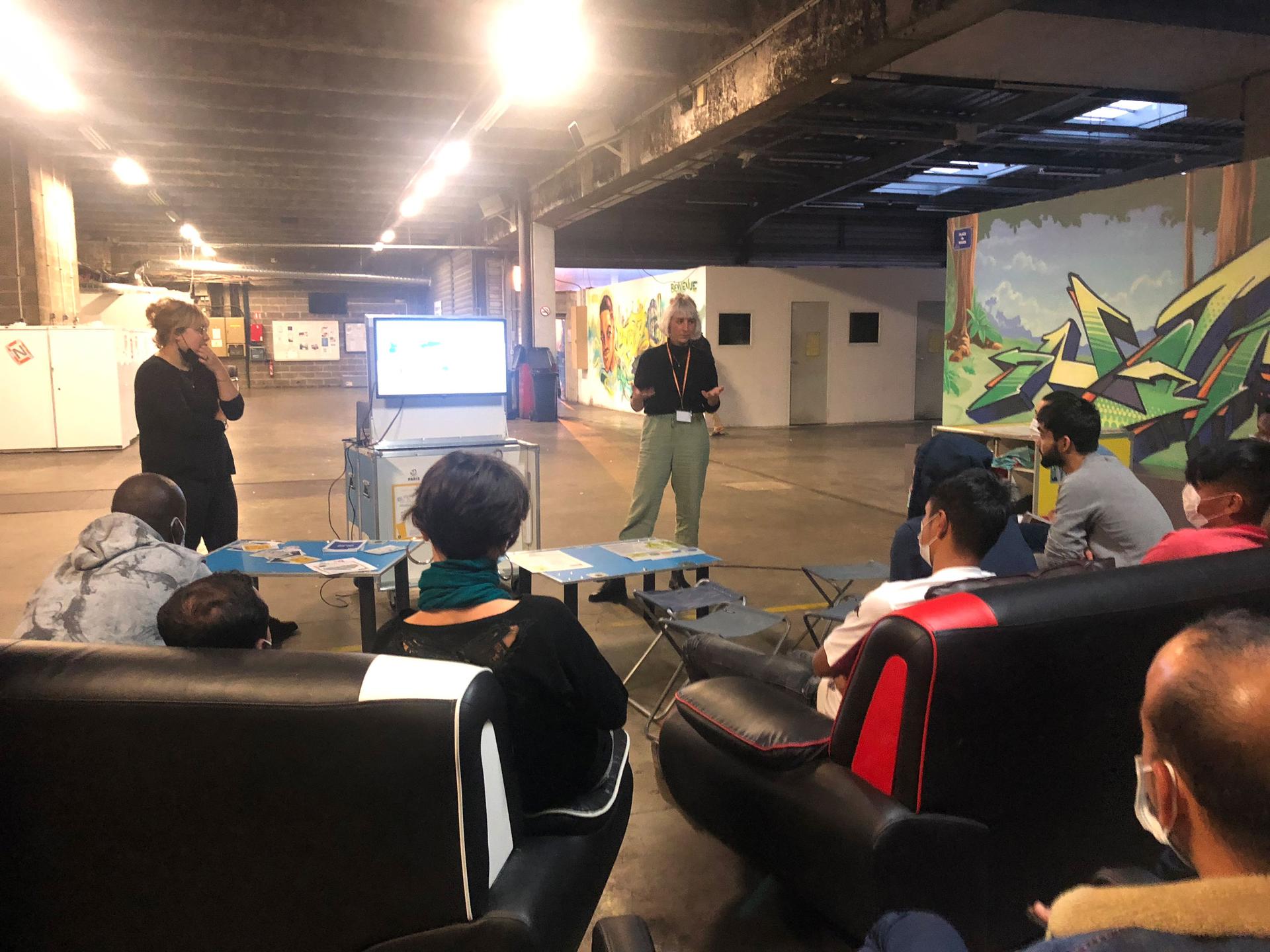

At a refugee shelter in southeast Paris, employees are trying to make the transition into French society a bit smoother.

“We believe that integration is about access to work and social housing — but it’s not only that.”

“We believe that integration is about access to work and social housing — but it’s not only that,” said Pauline Leclerc, the director of CARE, an association running the refugee shelter.

That’s why CARE offers a number of workshops for refugees meant to act as a complement to the training offered by the French Office of Immigration and Integration. There are lessons about how to write a CV and cover letter, but also more abstract discussions, for example, about democracy.

“It’s not only, ‘I’m going to show you with a Power Point and you will understand what democracy is,’ but it’s more about creating a debate and a discussion,” Leclerc said. “These things take time.”

On one occasion, a 26-year-old social worker named Océane Viltard is leading a workshop about the environment and ecology. He covers practical points, like how in France, tap water is safe to drink. Later, there’s a debate about vegetarianism.

Ahmed Mohammed, originally from Afghanistan, said he enjoys these workshops.

But overall, he’s found life in France difficult.

Mohammed used to live in Sweden.

“I didn’t have problems in Sweden, everyone was welcome for me there,” Mohammed said.

Whereas in France, he’s struggled with integration.

“I give my stay here, maybe, a three out of 10,” Mohammed said with a laugh.

Despite the fact that he’s now fluent in French, he said he’s hardly been able to make any French friends. Which is a shame because, for him, integration isn’t simply about learning values. It’s about feeling welcome.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?