Mohammed Rezuwan is on a rescue mission: The 24-year-old who lives in Cox’s Bazar — the world’s largest refugee camp — is working to save Rohingya traditional stories before a generation of storytellers dies off.

Rohingya people have lived in the region for over a thousand years, but Myanmar’s government considers them foreigners from neighboring Bangladesh. Over the last four years, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have been driven out of Myanmar by government troops and local militias. Many now live in dozens of refugee camps.

“We, Rohingya people, have our own culture, tradition. We are on the brink of losing all of them, unfortunately.”

“We, Rohingya people, have our own culture, tradition. We are on the brink of losing all of them, unfortunately,” Rezuwan said in a WhatsApp voice message from Kutupalong, one of more than two dozen encampments in Cox’s Bazar, on the coast of Bangladesh.

The crowded area accommodates families who live in tents and shelters along narrow alleyways. United Nations figures put the exile population in the camp at nearly a million — four times the number of Rohingya still living in Myanmar.

Rezuwan lives in a bamboo shelter with his wife, his mother, a brother and a sister. The family fled their home in Maung Daw, in the Rakhine district of Myanmar, on Aug. 25, 2017, as their village was set ablaze in a campaign that has forced most Rohingya out of Rakhine.

“I remember the gunshots ringing out like thunderclaps, the bullets strafing the sky like clouds of hungry locusts,” Rezuwan wrote in the author’s note of his book, Rohingya Folktales: Stories from Arakan, as told by Rohingya refugees.

“On that terrible day, my family and I ran to a nearby mountain where we hid for three days before we decided to cross the border to Bangladesh.”

A quest to gather stories

In 2020, after several years at Cox’s Bazar, he took on the role of folklorist — recording stories passed along in the oral tradition by Rohingya elders.

“Folk tales are used by Rohingya people to teach morals and lessons to their youngsters,” he said. “I, myself, decided to make a book.”

Rezuwan speaks his native Rohingya and learned to speak and write Burmese in school, but his English is largely self-taught. He spent a year collecting material for his English-language book, and the online version now includes 19 stories from storytellers in several of Cox’s Bazar’s camps.

Research was no easy task. Rezuwan doesn’t have a car or bike, so he walked, sometimes up to five miles, to meet with each storyteller and record his or her story on the phone. COVID-19 restrictions added further complications.

“The hardest part is finding and meeting the people from different sorts of camps,” Rezuwan said. “After all, not everyone has the same talents to remember the stories — just because they are uneducated — and so, finding the right person to tell the story was finding a gem from the ocean.”

The Rohingya language is primarily spoken, without a standardized written script. Rezuwan translated the stories by playing back his recordings and, word by word, constructing English versions of the tales. He then pasted them into WhatsApp and sent them to his editor and friend, Alex Ebsary, in Buffalo, New York, who corrected grammar and word usage. Ebsary said he intentionally edited the stories with a light touch.

“Folktales are not a universal language. … You know, if you read these folktales, some of them are quirky. They’re kind of not even the morals that I would think of when thinking of a folktale.”

“Folktales are not a universal language,” he said in a phone interview. “You know, if you read these folktales, some of them are quirky. They’re kind of not even the morals that I would think of when thinking of a folktale.”

In the story, “The Blind Mother,” a man is coaxed into bringing his blind elderly mother into the woods to be eaten by tigers.

“The Foolish Villagers” is another story with an unexpected plot, he said. “An orphan boy is mistreated by some of the villagers and he decides to seek revenge on them by tricking them into selling all their cows, burning down their house and then eventually tying themselves to a stake in the middle of an estuary that floods and drowns all of them.”

Rezuwan said his mother used to tell him the story known as “A Hunter and a Flock of Heron.” The version he collected from Rashid Ahmod, a 60-year-old resident of Kutapalong, was essentially the same story he heard as a boy, he said.

The story is about a hunter who catches a group of beautiful herons in his net. The herons all try to escape by flying around in all directions, Ebsary explained. Rezuwan said the moral of the story is that birds — and people — can’t manage to go anywhere until they cooperate.

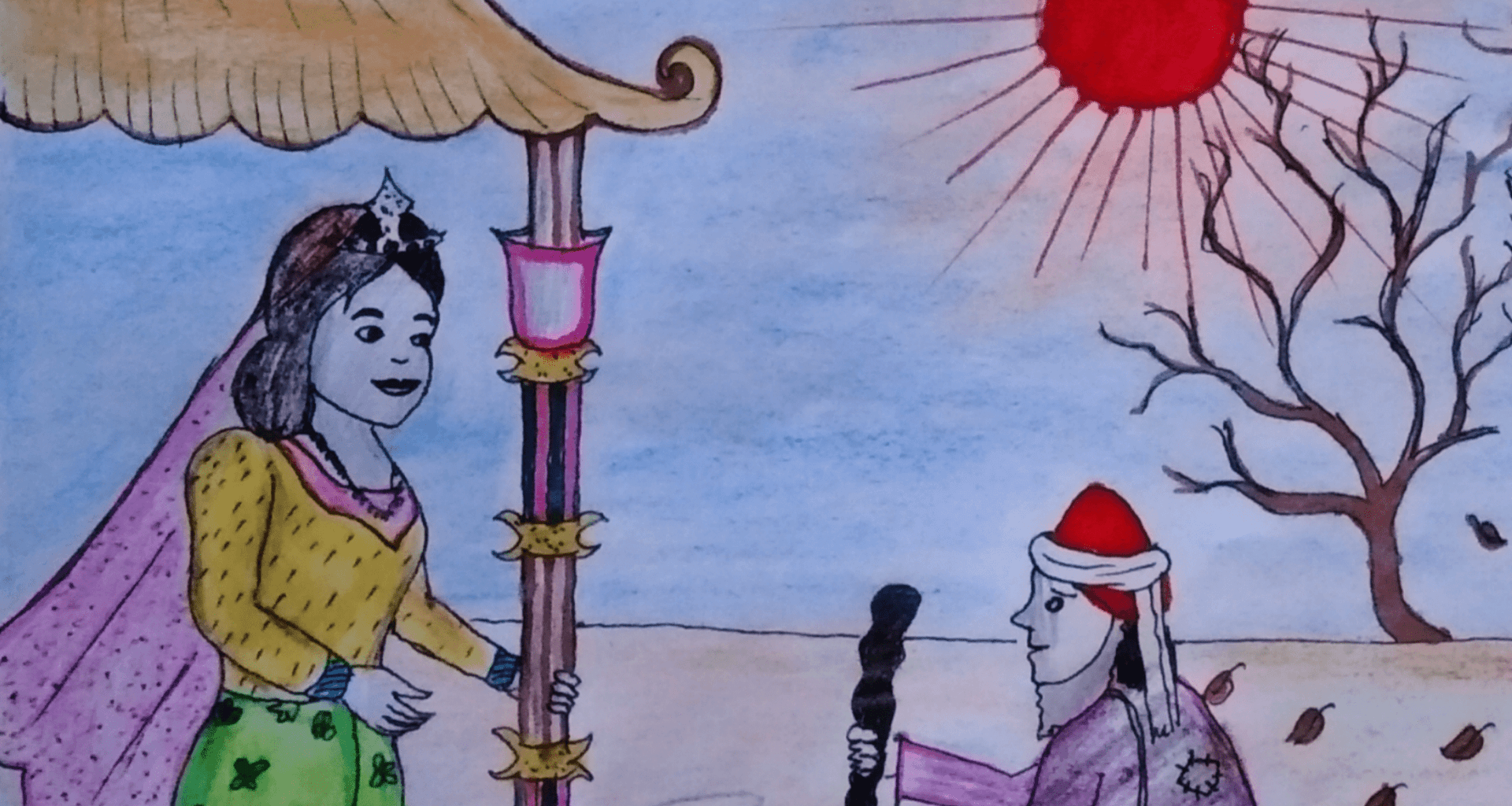

Rezuwan and Ebsary both singled out a story from the collection called “A Queen’s Dream,” which could serve as an allegory for Rohingya as an ethnic minority.

The story is about a powerful queen who has a vivid dream about torrential rains after a period of drought. Everyone who drinks from the rain loses their minds. So the queen sends advisers to warn everyone.

“But of course, they don’t listen and everyone drinks the rain and goes mad. And in the end, the queen decides to join them by drinking the rain herself,” Rezuwan said.

The moral of the story is that if a country’s majority are wrongdoers, they have the power to “force [the] entire country into a very bad situation,” Rezuwan said. “It’s what we are facing right now.”

A message to the world

Rohingya have long faced discrimination and marginalization in their home country. The United Nations has called it “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” If life in Myanmar was untenable, Rezuwan said, “in [the] camps, it seems like we are facing the second genocide.”

Since coming to Kutupalong, Rezuwan has organized an educational network where Rohingya children — unable to attend schools — can follow the same curriculum taught in Myanmar. He also works with humanitarian groups as a guide and interpreter.

He sees the book as his contribution to the preservation of Rohingya culture and intentionally published it in English to reach an international audience.

“I wanted the international community to know about our culture, about tradition and about the existence of Rohingya people in Arakan,” he said.

Arakan, the name Rohingya people give to their homeland in Myanmar, no longer appears on any maps of the region forming the present-day Rakhine State.

But it’s Arakan — and its stories — that Mohammed Rezuwan wants us to remember.