‘We will not leave Brasilia defeated’: Brazilian Indigenous groups mobilize to defend land rights

The chants of Native peoples have echoed across Brazil’s capital over the last week and a half.

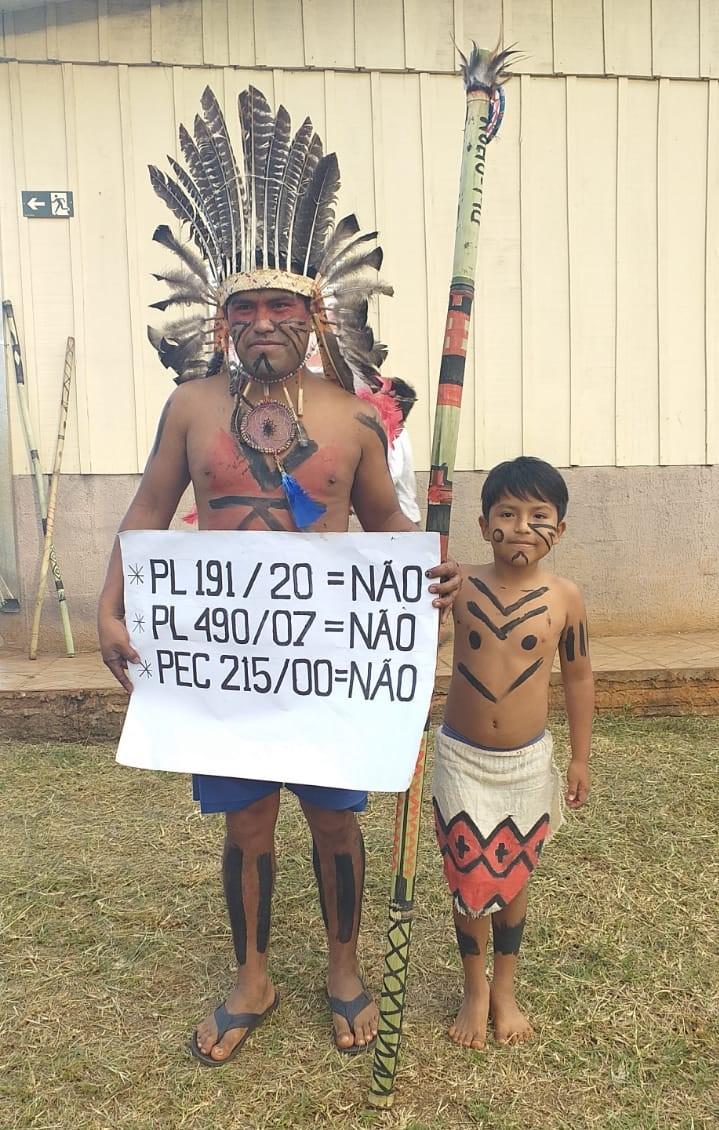

About 850 members of nearly four dozen Brazilian Indigenous tribes are camped in Brasilia, just a short walk from Congress and rows of government buildings, to fight for Indigenous land rights currently under consideration in Brazil’s courts and Congress.

In Brasilia, Indigenous representative Joenia Wapichana is fighting against a bill known as PL 490 that, if passed, would weaken Indigenous peoples’ land rights and open the door to extractive industries.

On Tuesday, police fired tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets against hundreds of Indigenous protesters as the Justice and Constitution committee was expected to vote on the legislation. An earlier vote on the bill was postponed last week, amid the protests.

Allies of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro are looking to push the controversial bill through Congress.

“We want to bury this bill,” said Edinho Macuxi, an Indigenous leader from the state of Roraima, outside of Congress. “We will not leave Brasilia defeated.”

Protesters have shut down streets, demonstrated in front of the Mining Ministry, and marched to the Copa America soccer tournament.

Related: Gold rush in Brazil threatens Yanomami Indigenous people

“There are Indigenous peoples from across Brazil here. … We are resisting and more Indigenous people are on their way.”

“There are Indigenous peoples from across Brazil here,” said Ricardo Pataxó, a young Pataxó leader wearing a face mask and a beaded necklace, in a video shared online. “We are resisting and more Indigenous people are on their way.”

Their actions have been shared in countless videos over social media.

This is the most active Indigenous mobilization in Brazil since the start of the pandemic and was organized by the country’s largest Indigenous organizations, including the Brazilian Network of Indigenous Peoples, APIB.

Related: Copa America soccer championship in Brazil draws protest

In a video sent to The World by groups on the ground, rows of Indigenous men wearing armbands and feathered headdresses chant behind a metal fence. Before them, a pack of policemen block the locked entrance into a Congressional building.

‘Do or die’ moment

Those camped in Brasilia are battling on multiple fronts.

Protesters have also demonstrated in front of Brazil’s Supreme Court, which is expected to decide over a key case this month that impacts 23,000 hectares of land belonging to the Xokleng people from southern Brazil.

The courts could either affirm Indigenous land rights or set a precedent by stripping territorial rights that were not officially recognized when the Brazilian Constitution was approved in 1988.

Brasílio Priprá, leader of the Xokleng people, says that would be a tragedy. He says that for thousands of years, the Xokleng lived all across southern Brazil, and that today, less than 500 families remain on their territory.

Related: Protesters across Brazil call for Bolsonaro’s ouster

“We need the court to recognize the rights of Indigenous peoples, because we have always lived on these lands.”

“We need the court to recognize the rights of Indigenous peoples, because we have always lived on these lands,” he said.

In many ways, the country’s Native peoples camped in Brasilia see this moment as “do or die.”

Brazil’s Constitution protects their rights and their territories, but Bolsonaro has revived policies and a mindset left over from the Brazilian dictatorship of the 1960s and ’70s, which believed Brazil’s Native peoples should integrate with society — or get out of the way of the country’s development.

This is a central theme running through both their battle in Congress and in Brazil’s highest court.

For the first time as president, Bolsonaro visited an Indigenous community late last month in the western Amazon, where he inaugurated a footbridge.

“There are people that treat them as though they need to be hidden in their reservations,” Bolsonaro told cameras. “They don’t want them to evolve. They don’t want them to cultivate and exploit their land, to mine, to build small hydroelectric dams,” he said.

Some of Brazil’s Native peoples may want this.

But not those fighting for their survival in Brasilia.

‘Land for us is like our mother’

Last week, hundreds from the encampment in Brasilia protested outside Funai, Brazil’s Bureau for Indian Affairs, and demanded that director Marcelo Xavier be removed. In an open letter, they said he was negotiating their lives for the benefit of agri-business interests and illegal mining.

Police responded with pepper spray and tear gas bombs.

Indigenous activist Sonia Guajajara filmed the scene and shared it over Twitter.

“This is how Funai receives Indigenous peoples,” she said.

The occupation in Brasilia is expected to stretch on at least through the end of the month, when the Supreme Court is scheduled to rule.

Native peoples know that even if they win in the courts and also defeat the bill in Congress, it doesn’t end their on-going battle to defend their rights, their territory, and the future of their people.

“We don’t want this land to sell or destroy it,” said Priprá, his voice shaking as he fought back tears.

“Land for us is like our mother. You don’t trade or sell it. So it’s emotional that we are all here together, united. It’s not just for us, it’s for the world.”

“Land for us is like our mother. You don’t trade or sell it. So it’s emotional that we are all here together, united. It’s not just for us, it’s for the world.”