Vinzavod, a former wine factory in central Moscow, has been converted into a space for contemporary art.

In this relaxed place that attracts a youthful crowd, it may be easy to forget the bleak political mood in Russia, and the Kremlin’s ongoing crackdown on opposition voices.

Related: ‘Fighting corruption in Russia is now being called extremism,’ says Alexei Navalny’s top strategist

But artist Katya Muromtseva‘s latest multimedia exhibition that opened last month ensures that anti-Kremlin voices are heard.

The 31-year-old artist uses her artwork to call attention to the uptick in arrests of opposition activists and the forced closures of independent media.

“This show is based on interviews that I made with people from my generation,” Muromtseva said.

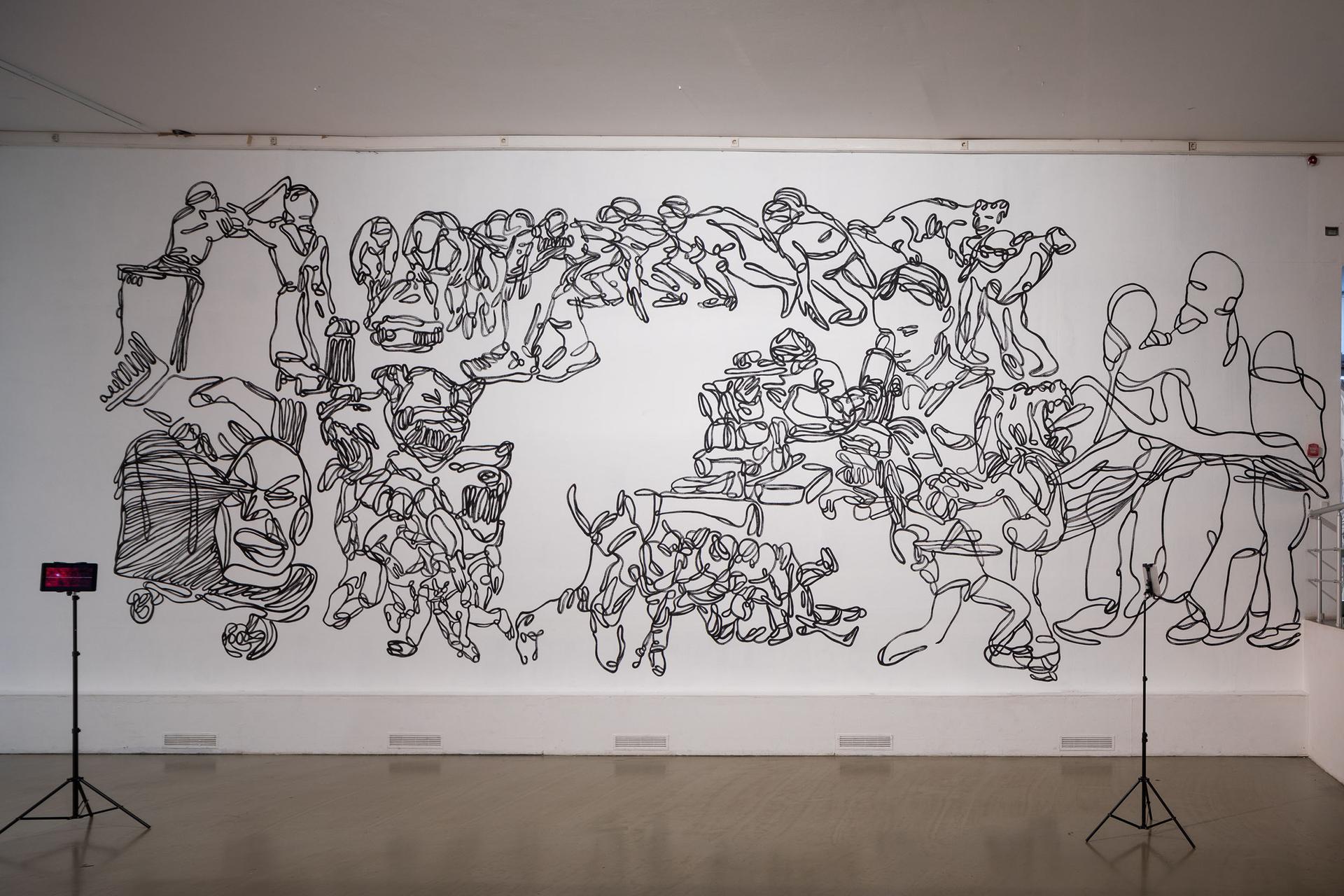

Walking into the exhibition, viewers are immediately struck by the huge mural that covers three high, white walls.

The mural is made up of lopping black lines in which the shapes of riot police and protestors emerge. The images evoke the mass demonstrations that broke out in the Russian capital earlier this year, against the jailing of opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

Related: Navalny’s health warrants ‘justified, grave concern,’ says adviser

On the fourth wall, a set of blood red paintings are covered with similar drawings.

Related: One small step: Moscow’s first queer dance festival challenges homophobia

Muromtseva said that the paintings are “not comfortable” because “the time when we are living — it is not comfortable.”

Beneath the wall art, five iPad screens display the text of interviews Muromtseva has gathered, which focus on moments of political awakening.

One person she spoke to volunteered to work as an election monitor, only to see ballot boxes being stuffed.

Another was a student who began traveling around Europe in 2014, and witnessed the outrage there over Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Related: Crimean Tatars face prosecution 7 years after Russia’s annexation

A third interview is with a man who used to sneak away from his wife at night to graffiti anti-Kremlin slogans around the city.

“A lot of people think that we cannot change anything. This is the government, they have the power. … But that’s not true.”

“A lot of people think that we cannot change anything. This is the government, they have the power,” Muromtseva said. “But that’s not true.”

Related: Russian opposition politician blasts ‘two dictatorships’

Russia’s ‘fearless generation’

Muromtseva is part of a generation that is causing concern for the Kremlin. People her age tend to be more openly opposed to Putin than older generations.

They also tend to get their news online, rather than from tightly-controlled state media.

“How can we trust the news? Because, it’s like we’re at the point where all the news is written by the state,” she said.

“So, for me, this is the new version of the news, how it can be written. It can be written only with these very particular, very individual emotional stories.”

Muromtseva describes herself as a “socially engaged” artist rather than a political one.

Previous projects include a video work based on interviews with children about what they imagine life was like in the Soviet Union. She’s also worked with older people to redecorate retirement homes.

Muromtseva is not the only Russian artist who deals with political themes, but her combination of art, social engagement and journalism is unusual.

It’s also potentially dangerous.

In recent months, authorities have arrested members of Pussy Riot, the performance art group. Police have shut down shows by an independent theater troupe called Teatr.doc. And another young artist in far eastern Russia, Yulia Tsvetkova, is also facing ongoing criminal charges because of her work.

Muromtseva said that several guests at the exhibition opening had expressed concern for her safety, because of the “open critique” of the state in the interviews.

She understands the concern and admits that this is a hard time for artists.

“But on the other hand, I think this is very fruitful for artists to have this kind of tension, because your voice really matters,” she said.

Not everyone shares Muromtseva’s upbeat outlook.

Sergei Khripun, the co-owner of XL Gallery inside Vinzavod, where the exhibition is running until the middle of next month, said he doesn’t “see a future in the way that Katya probably does.”

Khripun, who’s part of an older generation, has seen many protest movements before, including the one that brought down the Soviet Union 30 years ago. Khripun admires Muromtseva’s art, but he’s critical of the interviews.

“I see that these are young people. It’s their hopes, it’s their frustrations, whatever. Well, let’s see, if you consider asking them five or 10 years later.”

“They’re quite naive, I would say…I see that these are young people. It’s their hopes, it’s their frustrations, whatever. Well, let’s see, if you consider asking them five or 10 years later.”

Muromtseva is convinced that real change can come. She recently worked with Russian teenagers and this gave her hope.

“[Teenagers are] so open and fearless and they’re very politically engaged and they are really aware of what’s going on in our country. They are the future and we are the future.”

“They’re so open and fearless and they’re very politically engaged and they are really aware of what’s going on in our country. They are the future and we are the future.”

Russia is holding parliamentary elections in the fall, which the Kremlin-backed United Russia party is all but certain to win, despite its falling popularity.

With the opposition forced out of politics, it remains to be seen how Muromtseva’s “fearless generation” will make itself heard.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?