Sixteen-year-old Mohammed Amine has been sleeping inside St. John the Baptist Church at the Béguinage, in the center of Brussels, for almost a month.

Amine, originally from Morocco, isn’t homeless — he’s one of up to 200 undocumented migrants who have occupied the 17th-century church since the end of January.

Related: Afghan returnees struggle with unemployment, violence at home

The migrants are hoping to raise awareness about their lack of rights in Belgium, and are calling on the government to grant them legal status. Belgian Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration Sammy Mahdi has described their actions as “blackmail.”

On the door of the church hangs a makeshift sign: “Liberté, égalité, dignité,” or “Freedom, equality, dignity.”

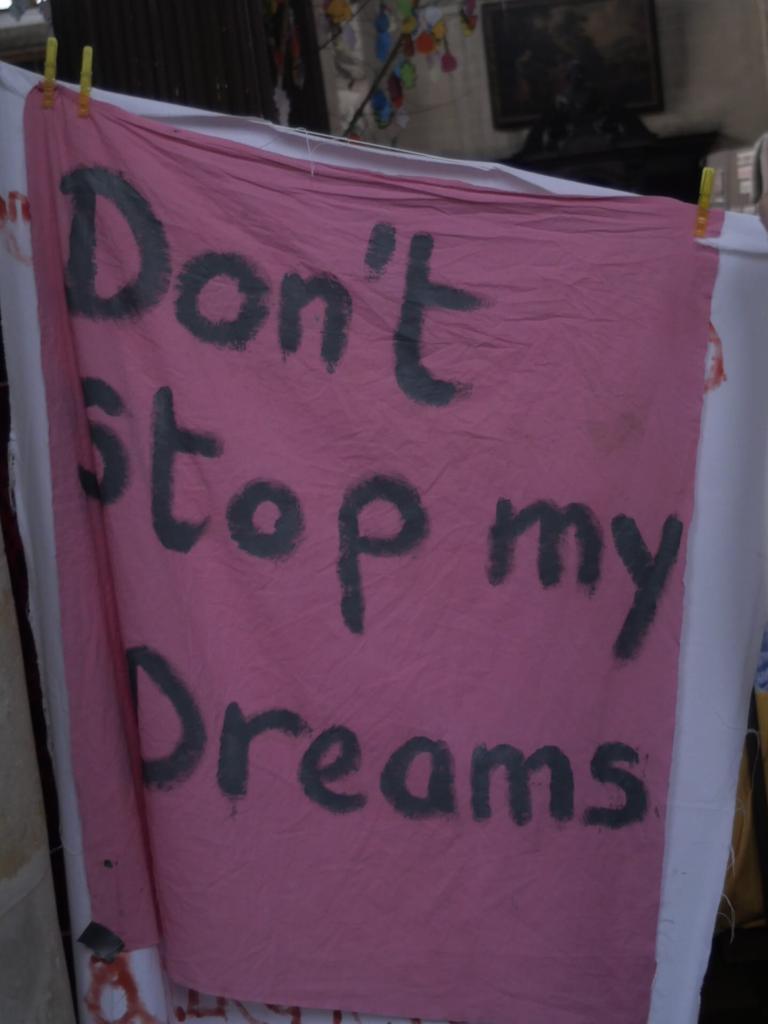

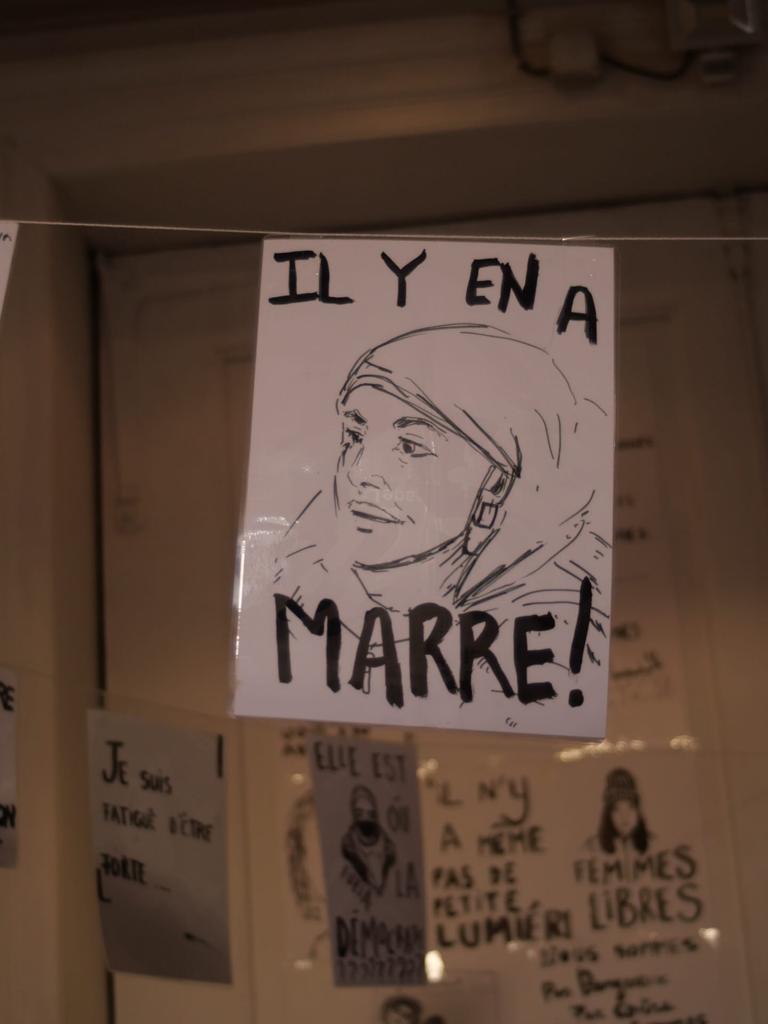

Inside the church, handmade banners read: “Je ne suis pas un esclave,” or “I am not a slave,” and “Travailler sans avoir peur de la police,” or “To work without fear of the police.”

Mattresses with blankets piled on top are spread out across the church floor, but Amine said it’s often bitterly cold inside.

“Since there are no heaters inside it is way too cold. It is, all the time, colder inside than outside the church,” he said.

Amine came to Belgium two years ago with his mother. The teenager said they were forced to leave as his father had become physically abusive. Amine’s parents were already divorced but he said his father continued to attack his mother and demand money from her. Neighbors didn’t intervene and Amine said his mother’s family refused to help because they were ashamed of her divorce.

Related: Thousands of children are stranded at a camp in northern Syria. Who will repatriate them?

“The neighbors couldn’t help her and my mother’s family couldn’t help her, since they could not accept the idea of a divorced woman in their family.”

“The neighbors couldn’t help her and my mother’s family couldn’t help her, since they could not accept the idea of a divorced woman in their family.”

Occupying a church in such large numbers is hardly ideal during a pandemic.

Karen Naessens, coordinator of the House of Compassion, a Catholic organization that works with the béguinage church to raise awareness of issues of injustice, worries about coronavirus contagion. But she said for many of the migrants, COVID-19 is the least of their concerns.

“They say, ‘We’re at the end of our tether, we already feel dead inside.’ They say, “We cannot have the coronavirus but we cannot continue like this either.””

There is no official data on the exact number of undocumented migrants in Belgium, but estimates range from anywhere between 120,000 and 200,000 people, said Ellen Desmet, assistant professor of migration law at Ghent University. Being undocumented means having very few rights in Belgium, Desmet said.

“The only rights you have as a migrant without papers in Belgium is that you have access to urgent medical care and you can have some material support. But for instance, you do not have the right to work in a legal way.”

“The only rights you have as a migrant without papers in Belgium is that you have access to urgent medical care and you can have some material support. But for instance, you do not have the right to work in a legal way.”

Related: UN rapporteur emphasizes responsibility to protect ‘vulnerable’ Hazaras

Desmet said the lack of labor rights leaves many undocumented migrants open to abuse by employers.

Amine’s mother works as a cleaner in restaurants and in other people’s homes. Most of the migrants occupying the church say they desperately want to work. The pandemic has made things a whole lot worse because many of the black-market jobs have also dried up.

Some migrants, like 19-year-old Nada, who declined to share her last name, visit the church during the day to join the protest but return home at night. Nada, also from Morocco, has been living in Belgium with her mother for the past five years. She said not having any legal status leaves her feeling trapped.

“You cannot do anything that you want. You cannot move, you cannot work. I want to continue my study in university, but I cannot. You feel like you are in a cage.”

The Brussels church has been the location of a number of major protests in the past, including in 1998, 2008 and 2009. Over the last 20 years, the building has experienced almost six years of occupation in total.

The migrants have reason to believe their demonstration might work. After some of the sit-ins, the government did grant temporary residency permits. But some of those protests also ended in a hunger strike.

Naessens said there has been mention of a hunger strike this time, too.

“I really hope it won’t happen, but I feel and see the desperation they have,” she said.

Related: Canary Islands face influx of migrants from West Africa

Immigration has been a thorny issue for the Belgian government. The previous coalition collapsed following a walkout by the Flemish nationalist party, the NVA, over migration policy.

It took 16 months for a new administration to take shape. The current coalition is made up of seven political parties, which makes it challenging to reach an agreement on any new immigration laws.

Professor Desmet said there was some optimism initially when the new secretary of state for asylum and migration, Mahdi, was appointed. Mahdi is the son of an Iraqi refugee who came to Belgium in 1970. But that hope is now fading, Desmet said.

“I think especially in the beginning, civil society organizations were quite hopeful. But now, already with a few months gone, the stance the secretary of state has taken is that he does not want to enter into negotiations with the migrants, as he considers it blackmail, in his own terms.”

Just days after the church protest began, Mahdi tweeted that occupying churches and demanding regularization (legalization) was blackmail.

“There will be no collective regularization,” he tweeted in Dutch.

Activist Joachim Debelder with Migrations Libres, a support group that works with undocumented migrants and refugees, said the fact that Mahdi responded so quickly was actually seen as a positive sign by some occupying the church. It showed the government was aware of their demands, and it brought more public attention to their plight.

But Debelder said Mahdi has also vowed to increase deportations and that a proposal by the previous government to create additional detention centers is still on track.

“There was a massive plan to build new detention centers, designed by the last coalition,” Debelder said. “They are keeping with this plan, you know. They say that they will make a big effort to increase deportations.”

Naessens, coordinator with the House of Compassion, said the migration minister has agreed to hold a meeting with the migrants but a date has not yet been set.

Nada said she cannot imagine what will happen if the minister doesn’t listen to their demands.

“He has to change his mind, he has to,” she insisted.

Amine said mass legalization of all undocumented migrants is the only solution. His mother hired a lawyer to help them apply for legal papers, but the lawyer put forward a poor case, leaving out much of the detail, he said. Their application failed. No matter what happens though, Amine said he cannot go back to Morocco. He is terrified of what his father might do.

“It’s not just about my life, it’s about my mother’s life, too. He could imprison her in the house or worse,” Amine said.

The teenager said he also worries that his mother could take her own life if they are deported back to Morocco, and he would be left completely alone.

Amine knows some of the protests in the past have lasted for months and even years, but he said now he cannot see any other option but to continue the occupation.

“I actually don’t care how long it will continue — we just want to have a result out of this.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?