A post-America world: Biden’s challenges begin at home, former diplomat Richard Haass says

A majority of Europeans think the United States’ political system is broken beyond repair — and that President Joe Biden will be unable to halt the country’s decline on the world stage as China fills the power void.

That’s according to a new survey by the European Council on Foreign Relations on how Europeans view the nation Biden is taking over after the tumultuous presidency of Donald Trump.

Former diplomat Richard Haass wrote recently that a “post-America world” may come sooner than we think — and that it’s been hastened by the Jan. 6 riots at the US Capitol. Haass is president of the Council on Foreign Relations and author of “The World: A Brief Introduction.” He spoke to The World’s host Marco Werman about the challenges the Biden administration faces.

Related: 5 major challenges facing Biden on Day One

Marco Werman: In a recent essay you wrote, you said that the crisis of the Capitol is hastening the arrival of a post-America world. Just explain that — the connection between the insurrection on Jan. 6 and this incoming post-America world and what that is going to look like.

Richard Haass: The connection is that the insurrection raised questions around the world, particularly on the part of our allies, as to our constancy. Even though Mr. Trump will be departing the Oval Office, it raised fundamental questions about the long-term trajectory of the United States, American society and American politics. In order to be an alliance leader, you need to be steadfast, reliable, predictable — and suddenly, those things seem to be in short supply. And more specifically, the concern is, even if Joe Biden is a familiar and traditional American president, what might follow him?

Something that you’ve written about and what’s echoed in that European Council on Foreign Relations poll is that many US allies are kind of looking at a pileup of disasters: the response to COVID-19, those Capital riots, police brutality, the attack on civil rights. And they’re saying we don’t think we can trust the United States to keep us secure anymore. So, how precisely do you think the global world order will shift as a result of that conclusion?

Well, I understand that conclusion because Jan. 6 was not a one-off. There are questions about American competence, obviously tied to COVID-19 and our inept response. The Charlottesville to George Floyd reaction showed a really divided society even before any of this. Opioid deaths, gun violence. Europeans and others look at the United States and they shake their head and they basically say, “We’re not sure we really recognize this country.” And the danger is they start taking matters into their own hands, not just them, but countries in the Middle East, countries in Asia. And they either start becoming much more autonomous, in which case American influence goes down. In some cases, they might defer or even assuage or appease a more powerful neighbor, Russia or China or Iran. We’ve seen elements of it started a few years ago. We saw the Saudis with the war in Yemen. We see Turkey now active in all sorts of areas. Europeans just went out on their own and signed their own economic deal with China.

All of this leads to a loss of American influence. And a lot of people say, “Well, what’s so bad about that?” Iraq was bad. Afghanistan was bad. But if you take a step back and you look at the last 75 years, this has been an extraordinary run. We’ve avoided great power conflict. Cold War ended on terms we could only dream about. We’ve seen it advance democracy. You’ve seen enormous improvement in living standards. And all this happened because of America’s unique position in the world. And the question is, are we in a position to sustain it? Are others prepared to, in some ways, allow us to continue it? And all of this, again, has been put into question.

I go back to George Bush’s speech in the early ’90s after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He said the US was the last superpower standing. I mean, that line kind of seems quaint now. Do you see China taking America’s place or is it possible there won’t be any sole superpower leading the way?

I remember that because I was working for the president at the White House. And when historians look at these 30 years, they were going to scratch their heads about how the United States could have gone from that pinnacle of extraordinary influence to where we are now. And what’s interesting, it’s come about only in part because of things like the rise of China or proliferation. It’s mainly come about, I think, because of what we’ve done to ourselves, a lot of which we’ve seen come to a head over the last few weeks. But this is a different world. There’s some things we can’t control. One of them is China’s rise. Another is the emergence of a Russia much more willing to use military force and other tools, like cybertools, to have its way. We’ve seen the spread of nuclear weapons and missiles to North Korea. We’ve seen the emergence of a much more aggressive Iran. So, in many ways, this is a world of much more distributed power, much more authoritarian, much less democratic. So you’ve got these changes in and of themselves. At the same time, you’re having a United States that’s having second or third thoughts about its willingness to play a large world role. And what we’re also seeing is questions about our capacity to play that role.

Wasn’t a post-America world to some degree inevitable? I mean, superpowers or empires, whatever you want to call it, they do rise and they do fall.

That’s a fair point, and there was no way that American ascendancy could be permanent. The question was when it would come to an end, how quickly and what it would give way to. And my biggest concern is that it’s coming as quickly as it is, and it’s not giving way to something that we helped design and bring about. I could imagine, like we did after World War II, we were in a unique position coming out of World War II. And in some ways, we designed the world where even though we were first among equals, others had a larger role. The Marshall Plan, the birth of various institutions. The difference between then and now is there hasn’t been anything like the same degree of design. And this world is just coming about and it’s much messier. It’s less free. It’s less organized economically. There’s virtually no organization to meet various global challenges. And it’s becoming more violent. So, this should give everybody pause.

Related: ‘I fear for our democracy,’ says Rep. Mondaire Jones in calling for Trump’s removal

Well, you mentioned the violence. After Jan. 6, we heard from some parts of America a sense of disbelief that this kind of crisis could happen in the United States. The idea of American exceptionalism is somewhat unshakable, especially in the Republican Party, despite lots of evidence to the contrary. How else do you see the idea of American exceptionalism eroding?

We’ve reached the point where we should put that phrase to rest. What I think we’ve shown is that democratic backsliding can happen here. We’re not immune. We’re not apart from history and some of the same trends we’ve seen in other countries, turns out they’re active here. So, we should get rid of, I think, the arrogance of that phrase. What we ought to focus on is simply living up to what we’re meant to be, which is that this is a country founded on opportunity and ideas. We’re supposed to stand for certain principles, and we’ve got to practice what we preach. If we’re going to be a voice for the spread of democracy, for human rights, for freedom around the world, for free markets and the rest, we have got to show that those work here at home. To put it another way, we’ve got to walk the walk. We can’t just talk the talk of exceptionalism.

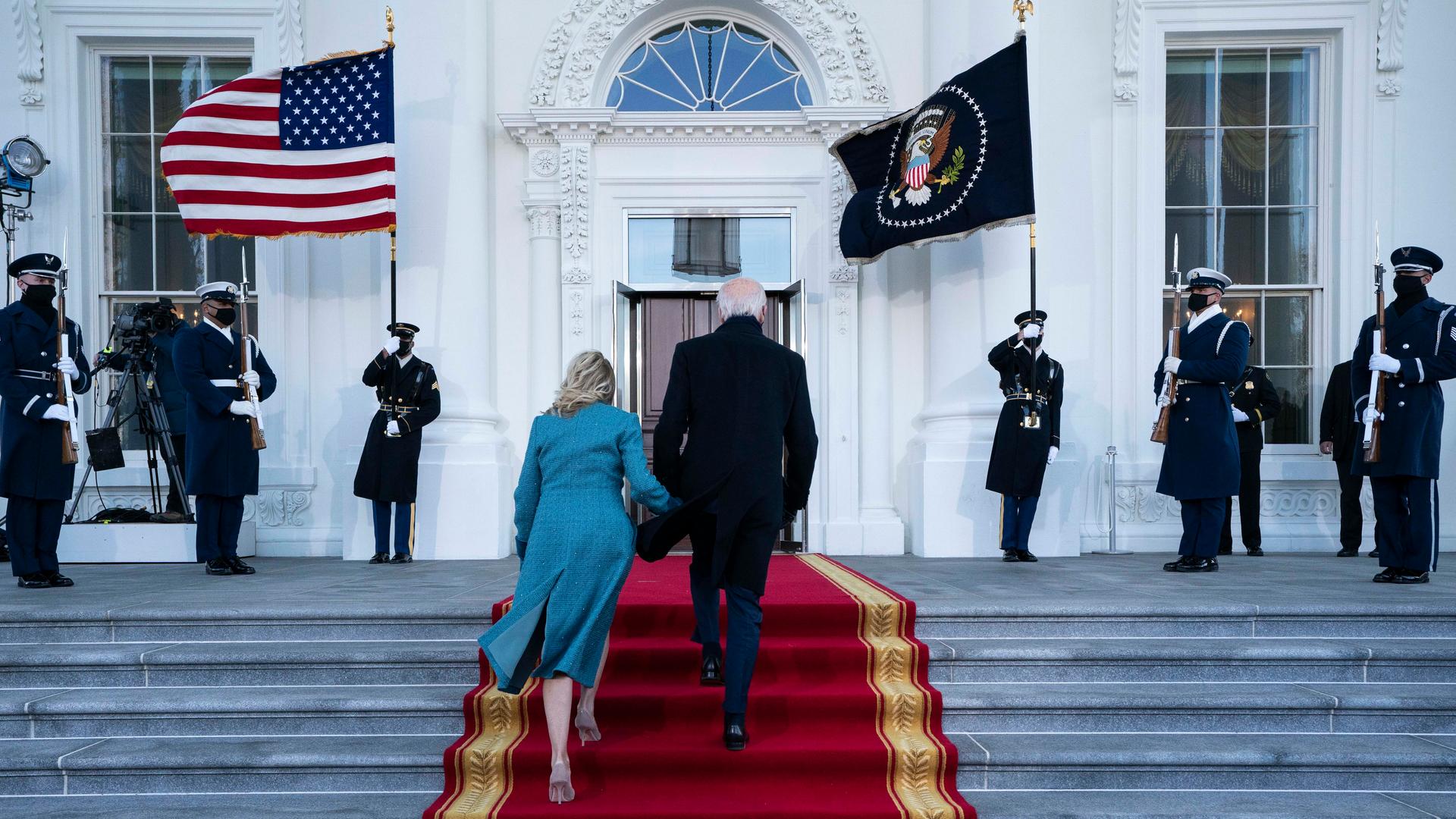

Right. I mean, this is now going to be the job of incoming President Joe Biden. So, where does he even begin to address that? Does it start at home with putting the US house in order, so to speak? Or should Biden do the rounds of world leaders and assure them that things will be repaired?

It should begin at home. I once wrote a book called “Foreign Policy Begins at Home.” And if it were ever true, never more so than now. Getting COVID-19 under control, getting the American economy growing, showing that American democracy can be both peaceful and functional. We have got to do all those things before we’re going to be in a position to reassert a considerable degree of influence. Now, I’m not saying we should put foreign policy on hold. The world doesn’t work that way. The world’s not going to say, “OK, you Americans sort yourself out, take a couple of years. And when you’re ready, we’ll be waiting for you.” You can’t do these things sequentially. But the United States has to understand its relationships will not be the same either with friends or foes. Our ability to promote human rights and democracy will not be the same until we have demonstrated that we have put our own house in order.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.