This analysis was featured in Critical State, a weekly newsletter from The World and Inkstick Media. Subscribe here.

For policymakers involved in conflict resolution, ceasefire announcements and peace treaty signing ceremonies usually bring some well-deserved relaxation. With the fighting over, they have time to pop some champagne, get some sleep and start writing their memoir about how pivotal they were to the peace process. For many civilians in conflict zones, however, the moment a conflict formally ends is the moment when their most difficult work begins. Post-conflict reconstruction — of built infrastructure, political bodies and social ties — is often grueling, decentralized and poorly compensated work. This week, Critical State takes a deep dive into recent research on what that work entails and the toll it can take on the people who are forced to take it on.

Related: Revolutions and lasting change: Part I

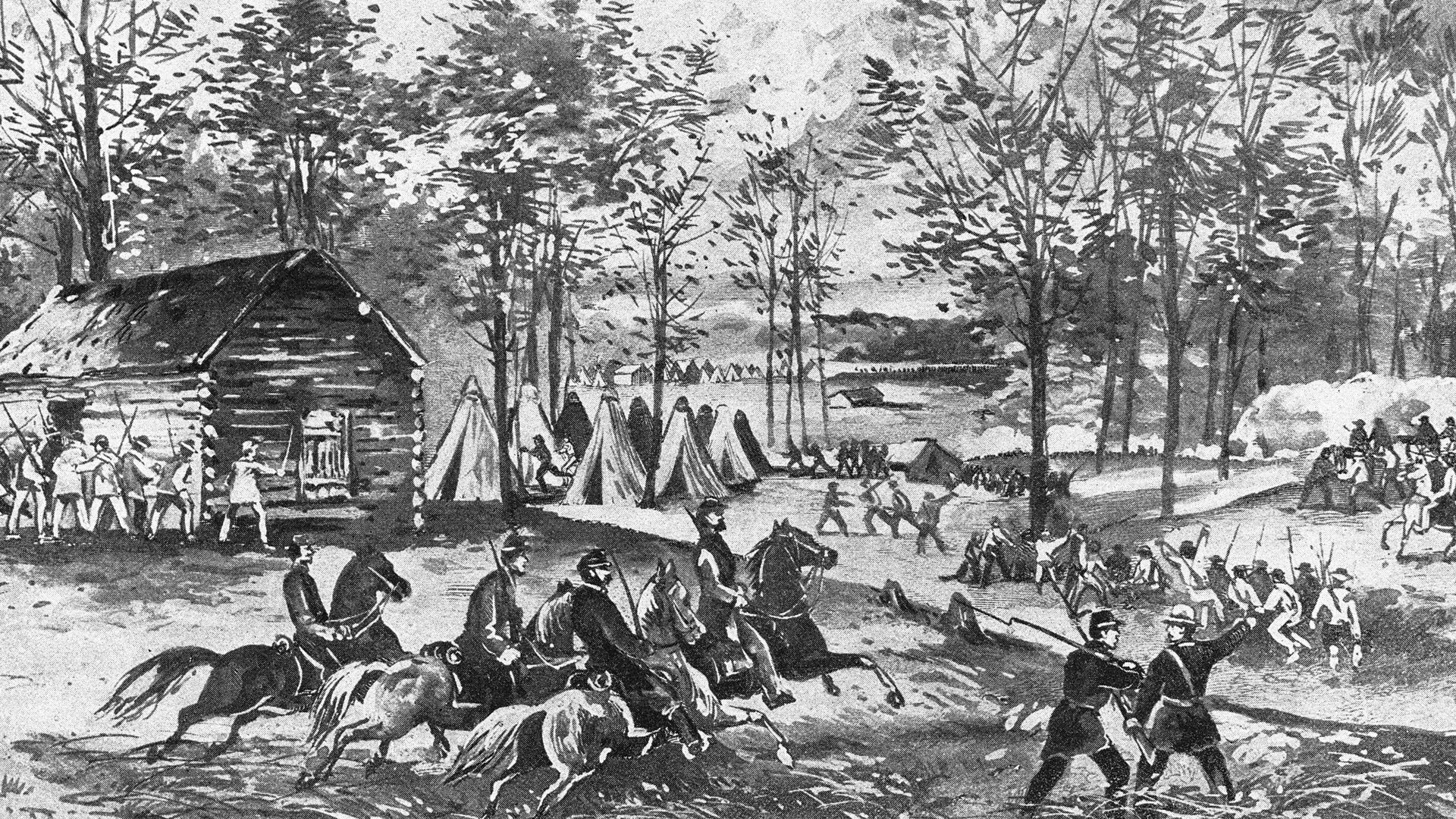

The US civil war produced more combat deaths than any war in US history, but still fewer than it might have if it had taken place a few years earlier. Medical advances before and during the war meant that many wounds that might have been fatal earlier were treatable — the percentage of US civil war soldiers surviving their wounds was more than twice what it had been in earlier American conflicts. Those treatments, however, often included amputation and other drastic measures that left patients carrying a disability for the rest of their lives. After the war’s end, their disabilities shaped the veterans’ capacity to participate in the postwar economy and it also shaped the lives of their children, who often had to support their ailing fathers.

In a 2020 article in the Journal of Health Economics, economists Dora Costa, Noelle Yetter, and Heather DeSomer investigate just how dramatically postwar lives were shaped by the work necessitated by war wounds. They drew on records of 6,228 Union Army veterans and 9,811 of those veterans’ children to track how their occupational and health outcomes changed over the years after the war ended.

For the veterans themselves, Costa et al. found more or less what you might expect: Wounded veterans who were older when they suffered their wounds were less able to change their occupations to suit their disability and suffered significant losses of wealth as a result. By 1870, the median older severely wounded veteran had 37% less wealth than the overall median veteran, and almost none of them had been able to leave repetitive, labor-intensive jobs in farming. Younger veterans had significantly more capacity to switch occupations, often leaving farming for either professional careers or less stable but more varied jobs as laborers. They suffered no significant wealth penalty.

Related: The long-lasting scars of Japanese American internment

For children of veterans with severe injuries, however, Costa et al. found that the costs of war wounds were durable, profound and extremely gendered. Sons of older wounded veterans were 5-12% less likely to become farmers — the most stable and sought after of the widely available professions in their generation — than their peers, but sons of younger wounded veterans saw no ill effects to their occupational class. Sons also saw no ill effects to their own mortality as a result of their fathers’ injuries.

Daughters, however, paid both wealth and mortality penalties for their fathers’ wounds. Daughters of severely wounded fathers were 8% less likely than their cohort to marry farmers, regardless of their fathers’ age. Once they reached 45 years old, daughters of older severely wounded veterans were 31% more likely to die in any given year than other members of their cohort. For daughters of older farmers — the veterans least likely to be able to find better employment opportunities after their injury — the hazard of early death increased to nearly 45%.

Costa et al. trace the early mortality effects to poor early-life conditions, which create cardiovascular problems later in life. Women with a severely wounded father were 138% more likely to die of heart problems than their peers whose fathers had avoided the worst of the war. The researchers attribute the gender gap in outcomes between sons and daughters to increased sensitivity to in-utero malnutrition among girls, but gender roles in the children’s lives may also have contributed to the gap. Girls, who worked inside, were more susceptible to childhood diseases than their brothers who worked in the fields, the researchers point out. In addition, if severely wounded fathers were forced to remain in farming, families might have used limited resources to feed sons — who were perceived as more capable of helping in the field — at the expense of daughters, whose mothers did not have physical disabilities from the war and therefore did not need as much immediate assistance.

Postwar work is often rendered invisible in historical accounts, so it should be no surprise that women often bear the greatest costs of it. The apportionment of the physical and emotional labor required to persevere after violence is no less gendered than the recruitment processes that determine who perpetuates the violence in the first place. As Costa et al. show, that labor and the costs associated with it can carry on long after the fighting comes to a close.

Critical State is your weekly fix of foreign policy without all the stuff you don’t need. It’s top news and accessible analysis for those who want an inside take without all the insider bs. Subscribe here.