Senegalese novelist Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s win is a landmark for African literature

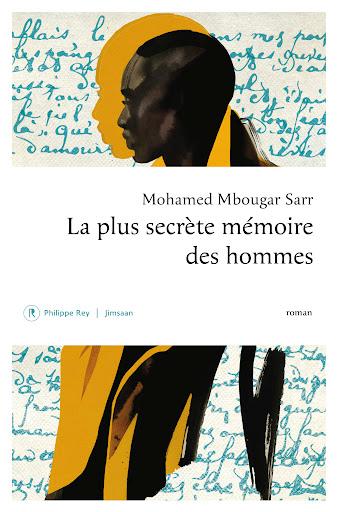

The Prix Goncourt — the oldest and most prestigious literary prize in France — has been awarded to 31-year-old Mohamed Mbougar Sarr from Senegal.

He’s the youngest winner since 1976 and the first from sub-Saharan Africa.

Critics have been raving about “The Most Secret Memory of Men,” his novel about a young Senegalese writer living in Paris. The jury made a unanimous decision to award Mbougar Sarr the prize after just one round of voting, calling his work “a hymn to literature.”

The prize will bring him literary fame and huge book sales, says Caroline D. Laurent, a specialist in Francophone African literature in France. She shared more about the author and his work, below.

Who is Mohamed Mbougar Sarr?

Author of the 2021 Prix Goncourt-winning novel “The Most Secret Memory of Men” (“La Plus Secrète Mémoire des Hommes“), Mbougar Sarr is a young Senegalese author who grew up outside Dakar and moved to Paris to continue his studies. At just 31, he has already published three other novels, his first in 2015: “Encircled Earth” (“Terre Ceinte“), “Silence of the Choir “(“Silence du Chœur“) and “Pure Men” (“De Purs Hommes“).

Starting his studies in Senegal, he began his doctorate at the prestigious School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris, working on poet and Senegal’s first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor. Writing got in the way and prevented him from ever finishing and graduating. He now lives in Beauvais, a city north of Paris.

What is the novel about?

“The Most Secret Memory of Men” plays with reality and fiction. It tells the story of a young Senegalese author, Diégane Latyr Faye, who lives in Paris. In high school in Senegal he had come across mentions of a mysterious novel published in 1938 by a Senegalese author called T.C. Elimane, “The Labyrinth of the Inhuman.” Unable to find a copy, he had put his quest aside, considering it to be one of the many lost books of literature. But, by chance a few years later, he meets a Senegalese writer, Siga D, who gives him a copy of the book. The reading (and numerous rereadings) of what he considers to be a masterpiece revives his desire to find out what happened to the mysterious T.C. Elimane.

Why does the book matter?

“The Most Secret Memory of Men” is a novel about writing and literature. It is full of literary references — like to celebrated Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño and prolific Polish author Witold Gombrowicz. But it’s the obscure references that are probably the most interesting: the fictional T.C. Elimane’s book and his fate echo that of real-life Malian author Yambo Ouologuem — who Mbougar Sarr’s own novel is dedicated to.

Winner of the 1968 Prix Renaudot for “Bound to Violence “(“Le Devoir de Violence”), Ouologuem sparked controversy after a 1972 article in the Times Literary Supplement claimed he had plagiarized several authors, including Graham Greene and André Schwarz-Bart. He returned to Mali and never published again. Just as the narrator of Mbougar Sarr’s novel, Diégane Latyr Faye, is his alter ego, T.C. Elimane is Ouologuem’s.

As much as it is about writing, “The Most Secret Memory of Men” is also about reading. The work is polyphonic (with many narrators besides Faye), it is transcultural (set in Europe, Africa and South America) and it mixes different literary genres (letters, articles, conversations), encouraging many different types of readings. Some may focus on the historical events depicted — the novel alludes to colonialism, the World Wars, Nazism and the Holocaust, the dictatorship in Argentina and recent Senegalese demonstrations against state corruption. Others may focus on the mysterious elements that recall some features of magical realism. Or on the literary references, both African and global, that punctuate the text. Or all of the above.

Why does this Prix Goncourt win matter?

For these reasons, winning the Prix Goncourt should be viewed as African literature finally being recognized for its literary qualities. One should focus on this (late) recognition and perhaps question why, faced with the many great novels by African writers, Mbougar Sarr’s win is so rare. “The Most Secret Memory of Men” is quite subversively brilliant in denouncing, through literature, the literary capture of African writers by former colonial powers.

Jointly published by two small publishing houses, Philippe Rey in France and Jimsaan in Senegal, the novel is truly transnational. The recognition of these publishing houses on two continents will, hopefully, enhance and help rebalance African countries’ role in publishing and distributing the works of their authors. Mohamed Mbougar Sarr is not only denouncing colonial and neocolonial practices but also encouraging new ways of publishing and reaching readers.

“The Most Secret Memory of Men” is a powerful text not only because of its writing, its themes, and what it says about the place of African literature in the world but also because of how it opens up future possibilities for Francophone authors.![]()

The author of this article, Caroline D. Laurent, is an assistant professor at the American University of Paris (AUP). This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!