There were hugs, smiles and a tight embrace at Toronto airport earlier this month as a 3-year-old Afghan boy reunited with his father.

The boy, who was not named because he is a minor, was separated from his family on Aug. 26, when there was a suicide attack at the Kabul airport in Afghanistan.

He was put on a plane out of the country and spent two weeks at an orphanage in Qatar, according to Qatari and Canadian media reports. Officials with the UN as well as the Qatari government helped reach his family in Canada, and he was able to reunite with them.

Related: ‘We are still here’: Afghan UN employees worry about their safety

But this boy is lucky.

In the chaos of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the mass evacuation from Kabul, a number of unaccompanied minors ended up on flights out of the country. Now comes the difficult task of reuniting them with their families or, for those who don’t have any relatives, helping them find new homes.

Right now, there are at least 300 Afghan children who were separated from their families during the evacuation, according to Wendy Young, president of Kids in Need of Defense, an organization that provides support for unaccompanied minors.

“We know of children whose parents were killed in the process, and we know of children who were separated and placed on a different flight than their parent or their guardian and the child is in one country and the parents in another.”

“We know of children whose parents were killed in the process, and we know of children who were separated and placed on a different flight than their parent or their guardian and the child is in one country and the parents in another,” she said.

Related: Minerals, drugs and China: How the Taliban might finance their new Afghan government

Young said that has spurred a global effort to help reunite Afghan children separated from their parents and also find housing for unaccompanied minors — children who evacuated with a friend or relative and also some who are orphans.

The US State Department and the Department of Health and Human Services didn’t respond to questions from The World about which countries unaccompanied Afghan minors have been relocated to, but earlier this month, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited some of them at Ramstein Air Base in Germany.

Some unaccompanied Afghan minors have started arriving in the US. This week, about 75 unaccompanied minors arrived in Chicago, according to city and federal officials, the Chicago Sun Times reported.

Others are staying at the Fort Bliss military base in El Paso, Texas, where Barbara Ammirati, deputy director for child protection in emergencies with Save the Children, has been part of the team offering support.

Ammirati said that when the children arrive and it is determined they are unaccompanied, they are immediately separated from the general population at the base and placed in shelters.

“It’s a very temporary accommodation,” she said. “It’s a small home — one room — and we’ve set it up. … it looks like a bedroom with a welcoming living space.”

No more than two minors, she said, stay in these facilities at a time and most of the minors she has worked with are between 15 and 17.

Ammirati said these Afghan kids have been through a traumatic experience, but they are ready to start their new lives in the US.

Related: Afghan women sidelined under new Taliban rule: ‘This country places no value on me as a woman’

“They are happy to be in the United States. The first questions are, ‘Can I go to school, if I go here, will I go to school?’ A university student is desperate to get back to classes,” she said.

Need for a more permanent status

Young, from Kids in Need of Defense, said she is concerned about the children’s immigration status because Afghan children fall into a unique category.

“They’ve been evacuated but they haven’t been processed and vetted as the rigorous and, frankly, bureaucratic and lengthy process that normally happens through refugee resettlement,” she said. “They haven’t spontaneously arrived here, so this is why they’re in parole status.” (An individual who is ineligible to enter the US as a refugee, immigrant or nonimmigrant may be “paroled” into the US by the Secretary of Homeland Security.)

Related: The Taliban want international recognition. Countries are debating.

That means they face a lot of uncertainty. Earlier this month, Young’s organization published a set of guidelines to protect Afghan children arriving in the US.

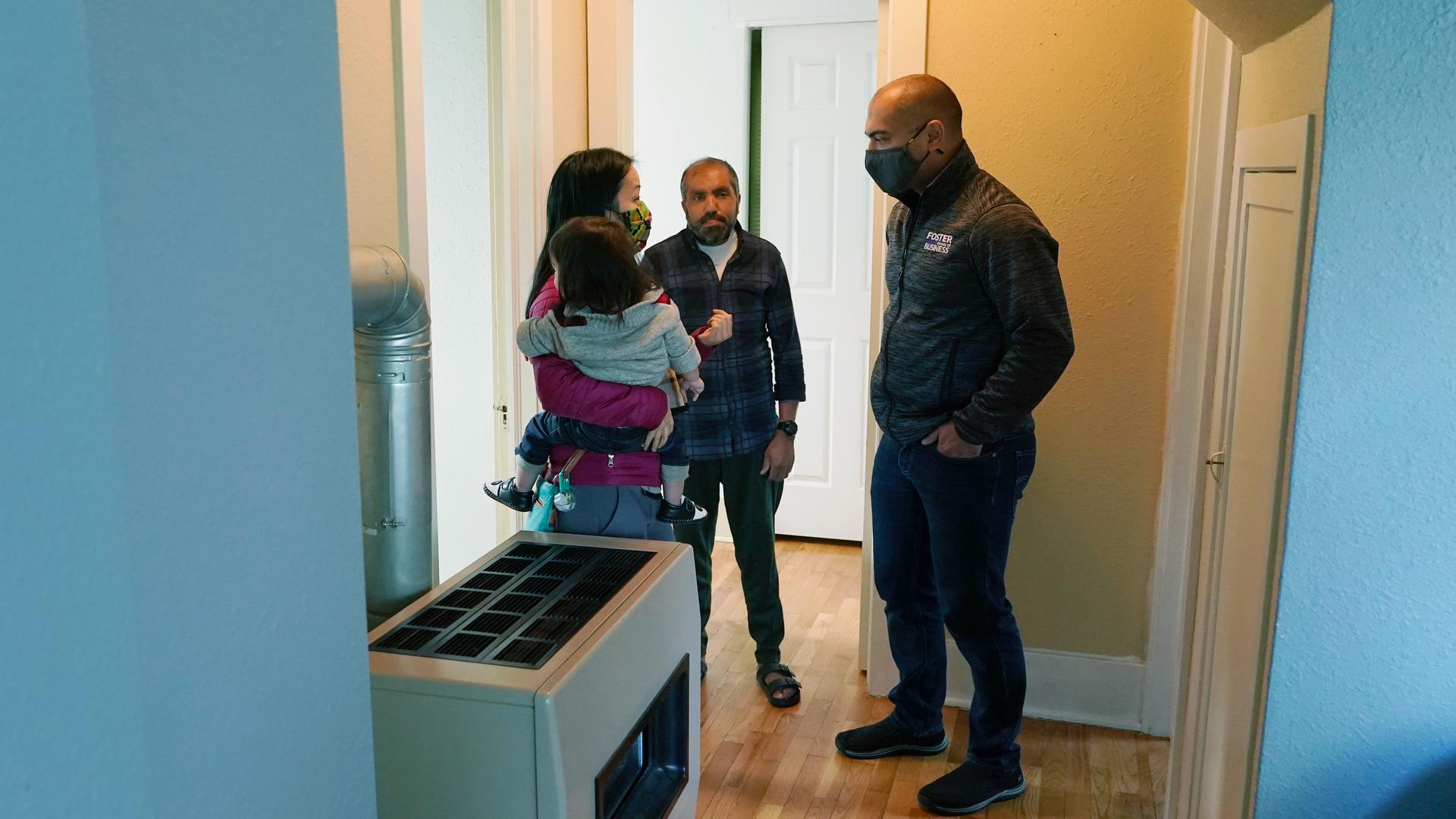

Meanwhile, people from Afghan communities in the US have been springing into action. For example, the Afghan American Foundation recently hosted a Zoom session to explain what becoming a foster parent entails.

Nadia Hashimi, a pediatrician and writer, started off the conversation.

“For these children, this may be an event in their lives that stays very fresh. I think trauma does that. Trauma has a very deep footprint on the soul and so the easier, and the more comforted we can have these children feel in this moment and this process, the better it is.”

“For these children, this may be an event in their lives that stays very fresh,” she said. “I think trauma does that. Trauma has a very deep footprint on the soul and so the easier, and the more comforted we can have these children feel in this moment and this process, the better it is.”

About 800 people across the country were on the call, Hashimi said.

Unaccompanied children arriving in the US is nothing new.

Young said in recent years, the official US response has been more about law enforcement than child protection. In the case of these Afghan children, she said, the approach is still a work in progress.

“What I hope happens is that we’ll look back at it and figure out what lessons learned there are because what we see whether you’re looking at the Central American situation or the Afghan situation is that these kids need our help,” she said. “And we owe it to them to have a system in place that kicks in rapidly and ensures that they get everything that they need including family reunification where appropriate.”