After Texas freeze, immigrants play critical role in repairing tens of thousands of homes

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story was originally produced by Houston Public Media and has been updated for The World.

For the last three weeks, Houston plumber Eduardo Dolande has been working long hours to help repair burst pipes in local homes and businesses.

Just in his own Houston neighborhood of Cypress, Dolande, who has worked as a plumber for 21 years, said he’s helped about a dozen families with their pipes — as a favor, free of charge. The destruction he’s seen inside some homes looks like something out of a movie, he said.

“It’s just wet sheetrock everywhere, and then the insulation that was up in the attic was on the floor. … It just looked horrible.”

“It’s just wet sheetrock everywhere, and then the insulation that was up in the attic was on the floor,” Dolande said, “It just looked horrible.”

One of the damaged homes was his own. At one point, he ran out of supplies to fix his own pipes after using them to help his neighbors. His plumber friends eventually helped him find some replacement parts, which have been in short supply since the storm.

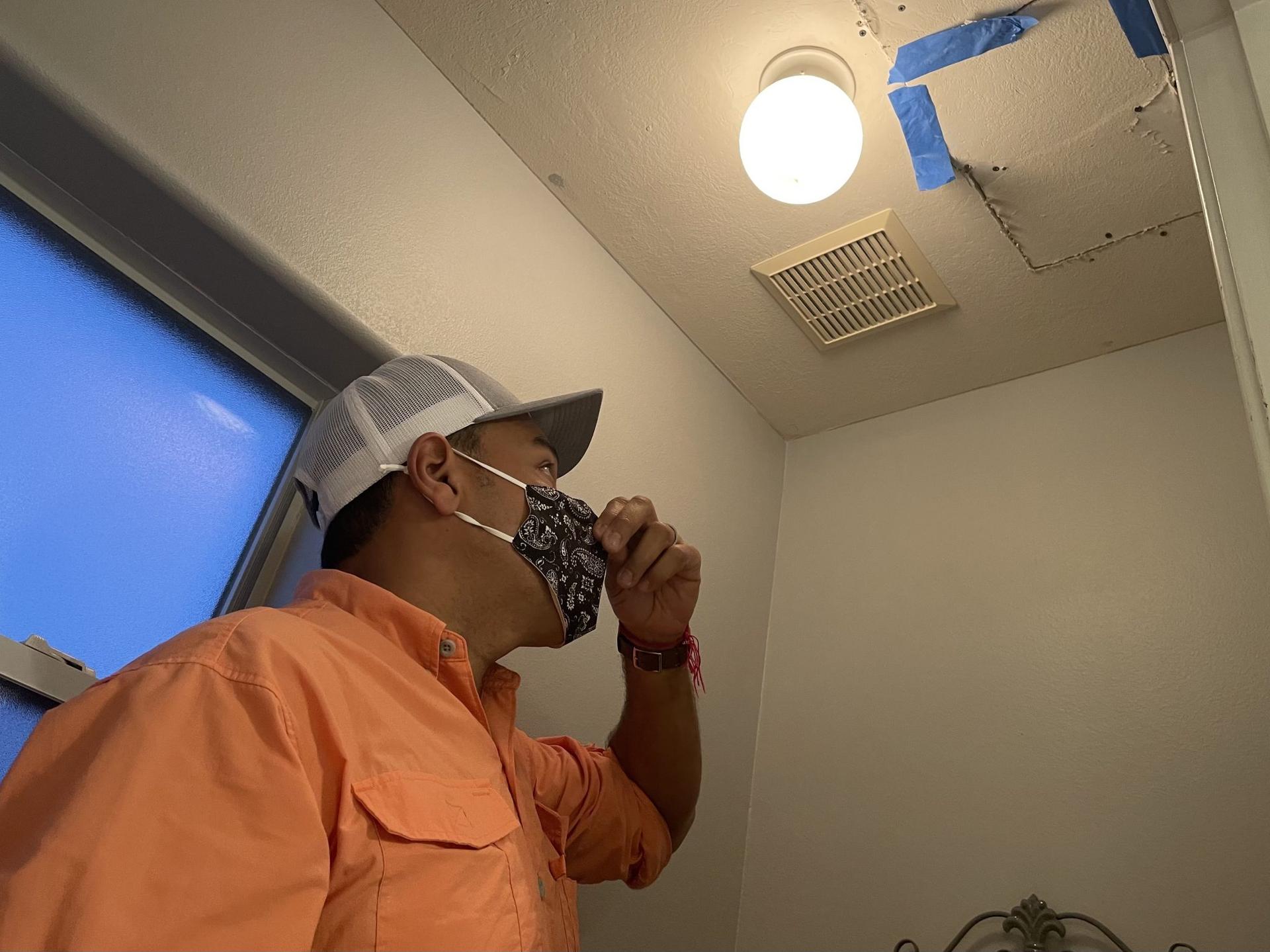

He had to cut open parts of his ceiling in two bathrooms and other parts of the house to reach busted pipes and repair them. Since he knew to turn off his water before the freeze, the damage in his own home was minimal — but the family still had water all over the floors while they tried to fix multiple burst pipes.

Dolande said his neighborhood was also hit hard by Hurricane Harvey, but that the freeze was worse because it took people by surprise.

“No power, no water,” Dolande said. “People get desperate over that.”

Related: Freezing temps wreak havoc on utilities in US and Mexico

“I’ve never seen that much damage in homes,” he said. “Never.”

Texas’ largest insurer, State Farm, has reported more than 44,000 claims in the state related to the winter storm. That’s more than 10 times the total number of burst pipe claims they saw nationally in 2020.

And immigrant workers — like Dolande, who is from Panama — are critical to repairing that damage, according to Jeremy Robbins, director of the New American Economy think tank.

“As people are trying to build back, they’re trying to repair their houses, they’re trying to figure out how to survive the damage, immigrants are playing outsized roles in so many of the professions that are essential to the Texas economy,” Robbins said.

The group’s analysis of 2019 American Community Survey data found that in the city of Houston, about 40% of plumbers and 63% of construction workers are foreign-born.

In Texas, 27% of the state’s plumbers and 40% of construction workers are foreign-born, though immigrants make up about 17% of the population. And the share of immigrant workers is even higher when other labor-intensive jobs are taken into consideration.

“If you look at drywall installers or ceiling tile installers and tapers, more than 75% of them nationwide are immigrants.”

“If you look at drywall installers or ceiling tile installers and tapers, more than 75% of them nationwide are immigrants,” Robbins said.

Related: From ‘aliens’ to ‘noncitizens’ – a Biden word change that matters

These workers will play a critical role as second responders, since many ceilings — like Dolande’s — have been damaged from burst pipes.

Steven Scarborough, strategic initiatives manager for the Center for Houston’s Future, said without immigrants, weeks-long repair wait times would last even longer.

“Imagine all these stories you’ve heard, how long people [are] waiting for plumbers, and increase that by 37%,” he said.

Related: Blackouts across northern Mexico highlight country’s energy dependence

Though these immigrant workers are essential to storm recovery in Houston, many come from communities that tend to be disproportionately impacted by catastrophic events.

A Rice University survey found nearly two-thirds of Hispanic immigrants in Houston could not come up with $400 to pay for an emergency expense. And those families are also less likely to reach out for aid in a crisis, Scarborough said.

Eduardo Dolande is a citizen — but many Texas plumbers and hundreds of thousands of construction workers are undocumented. And they’ve become a convenient political punching bag for Republicans in recent years.

During a press conference earlier this week, Governor Greg Abbott told Texans, “There is a crisis on the Texas border right now with the overwhelming number of people who are coming across the border.” Abbott often frames unauthorized immigration as a threat.

The governor also recently reopened the state and lifted the mask mandate — a move that confounded Jessica Diaz, who works with day laborers and other immigrant workers as legal manager for the Fe y Justicia Worker Center in Houston.

“I want to understand what his point of view is…how we came to the conclusion that this is a good idea?” she said.

Diaz said she’s concerned about lifting the mask mandate while less than 10% of the state has been fully vaccinated.

During the pandemic, her organization has received nearly 400 safety and health complaints. She said day laborers — who offer cheap, immediate repairs — put themselves in vulnerable situations to secure work.

“Whoever gets in the car the fastest is the one that’s going to get the job. You don’t even ask how much they’re going to pay you. You don’t even ask about the employer, who they are or where they’re taking you.”

“Whoever gets in the car the fastest is the one that’s going to get the job. You don’t even ask how much they’re going to pay you. You don’t even ask about the employer, who they are or where they’re taking you,” Diaz said.

In the four weeks after Hurricane Harvey, the University of Illinois found that more than a quarter of day laborers had experienced wage theft.

The Fe y Justicia Worker Center is already investigating wage theft claims from workers who helped with winter storm recovery.

“This is something we have seen repeatedly since Hurricane Harvey. Houston, in general, is a city that is in constant reconstruction mode,” she said.

The pattern of disaster, recovery and abuse is all too familiar — and Diaz said she doesn’t see anything changing soon.

Eduardo Dolande, who first came to the United States as a tourist in his early 20s, and became a citizen through his wife, Mitzila Guerra, said he hopes people can see that immigrants like him — including those without legal status — are helping the city rebuild.

“We are everywhere. We are helping everybody,” Dolande said. “Whether they say they don’t need us, or they don’t want to accept it, it is so obvious.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?