As Ethiopia’s civil conflict intensifies, the future for Chinese investment is uncertain

This essay is part of “On China’s New Silk Road,” a podcast by the Global Reporting Centre that tracks China’s global ambitions. Over nine episodes, Mary Kay Magistad, a former China correspondent for The World, partners with local journalists on five continents to uncover the effects of the most sweeping global infrastructure initiative in history.

The conflict between Ethiopia’s central government and local government forces in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region has sparked a humanitarian crisis with tens of thousands of refugees. It has threatened to destabilize a wider region in which China is heavily invested — a sobering reminder that grand plans, like China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), are only as good as ground truths allow them to be.

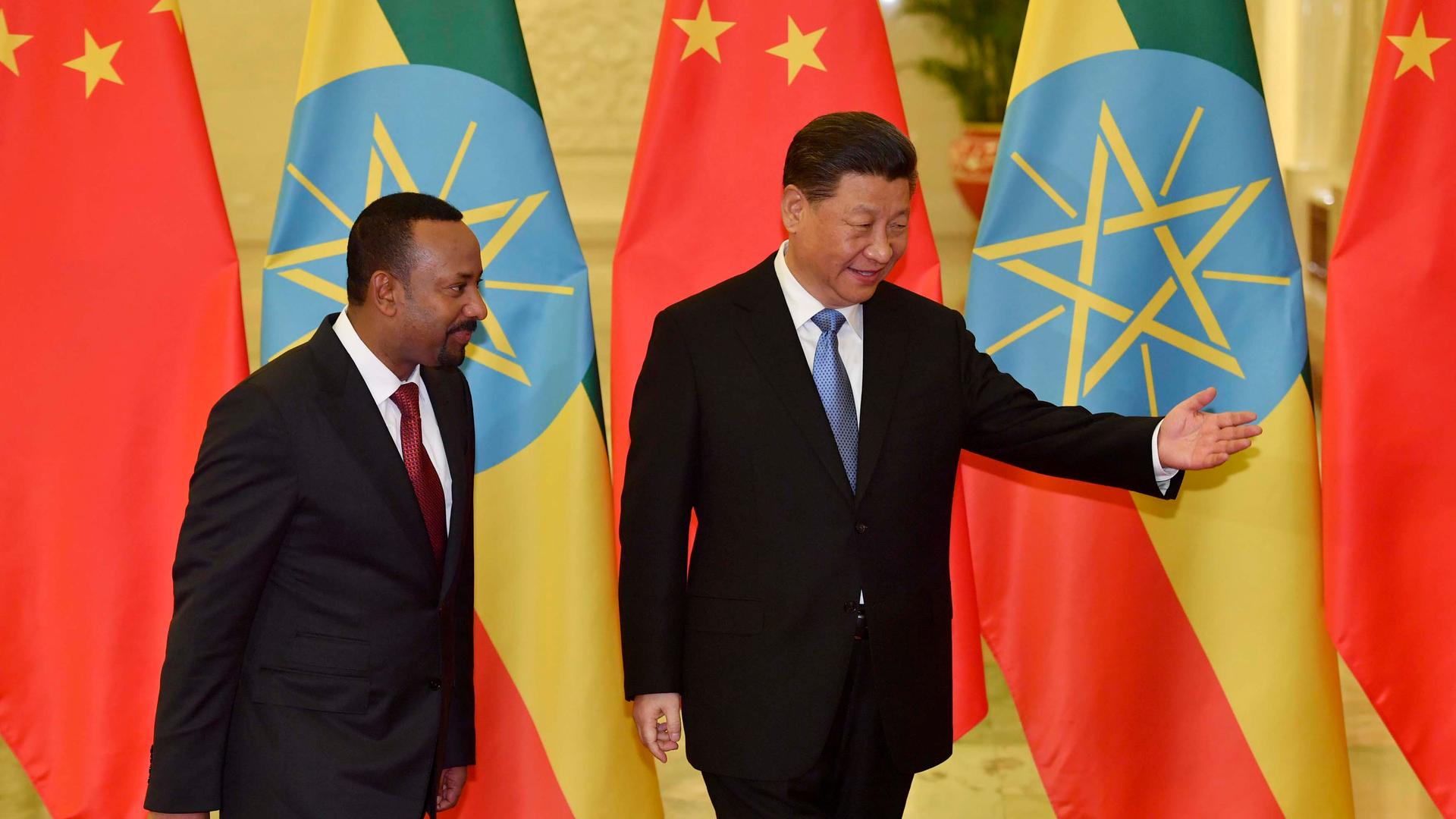

Despite all of Ethiopia’s success in recent years as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, ethnic and political rivalries are fierce and deep. And they haven’t gone away just because China has invested heavily there over the past two decades, or because Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for ending a war with neighboring Eritrea.

“We want the Horn of Africa to become a treasury of peace and progress,” Abiy said in his Nobel lecture in December 2019. “Indeed, we want the Horn of Africa to become the ‘Horn of Plenty’ for the rest of the continent.”

The Horn of Africa, which includes Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea and Ethiopia, has long been an area of strategic focus for world superpowers. It’s where the Gulf of Aden meets the Red Sea, in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait opposite Yemen, a strategic waterway for oil that leads all the way to the Suez Canal. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States fought proxy wars in Ethiopia and Somalia. Now, both the United States and China have military bases in the tiny coastal country of Djibouti, at a narrow part of the Strait.

Much of China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) involves building a belt of land routes and a maritime Silk Road of sea routes around the world, for both economic and strategic purposes. China’s many investments in Djibouti and Ethiopia include a railway that connects them and is also meant to connect Tigray’s capital of Mekelle to Djibouti.

Chinese investment has helped transform Ethiopia from one of the world’s poorest and most famine-prone countries to a model for the region of what’s possible — both in terms of rapid progress and self-sabotage of that progress.

Long before Chinese investment started in earnest in the early 2000s, Ethiopia’s central government fought long wars with Tigray and Eritrea, then both northern Ethiopian regions. The war with Eritrea stretched over 30 years; the war with Tigray lasted 17. Both wars ended in 1991, when Eritrea declared independence and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) took over the central government. Tigrayans stayed in power until political protests elevated Abiy to the prime minister in 2018.

Related: China’s new Silk Road runs through cyberspace, worrying rivals and privacy advocates

TPLF leaders have not gracefully accepted being shunted aside, despite Tigrayans making up just 6% of Ethiopia’s population. When Abiy started replacing Tigrayns in government, the TPLF left the unity party, retreated to Tigray, and conducted an election in September, in defiance of a government decision to postpone elections due to COVID-19.

Tigray’s regional militia is both well-armed and sizable with as many as 250,000 armed fighters. Its recent attack on a national government military base sparked the current conflict, which includes aerial bombing by the central government, in areas where Chinese companies have spent years building infrastructure.

While in power, Ethiopia’s Tigrayan prime ministers invited in Chinese investment to build desperately needed roads, dams, industrial parks and more throughout much of Ethiopia, at a time when many Western investors saw Ethiopia as too risky.

“China was courageous enough to get involved in such a market,” says Ethiopian economist Getachew Alemu. “So it really helped us. We used to have a huge backlog of demand for infrastructure, but we didn’t have the finance to finance it and push our economy forward. So, Chinese capital came as a savior for us.”

Related: Opening the door to Chinese investment comes with risks for Southeast Asian nations

China counts the billions of dollars invested in or lent to Ethiopia as part of China’s BRI. By the Chinese government’s calculation, some 140 countries have signed on in some way, including 44 African countries, drawing closer to China over the past two decades under the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation.

“Always standing on an equal footing, China respects African countries’ own decision-making rights, and lets African economies go into global markets through the Chinese market,” wrote Wei Jianguo, a former Chinese vice-minister of commerce in the Chinese Communist Party-run newspaper, The Global Times.

Wei counts China’s successes in Africa over the past two decades: building 3,750 miles of railways and roads, and “almost 20 ports, more than 80 large-scale power facilities…more than 130 hospitals and medical centers and more than 170 schools, which have brought significant progress to Africa’s economic and social development.”

China’s approach in Africa has received mixed reviews from Africans. The African survey group Afrobarometer found in a survey in 36 African countries in 2014-15, that 63% of Africans surveyed had a favorable view of China. And some African leaders prefer Chinese loans because Chinese lenders aren’t particular, like the World Bank and IMF are, about human rights conditions, corruption levels and whether a project can generate enough economic growth to repay the loan.

But Chinese loans often have higher interest rates and shorter repayment schedules. By contrast, Abiy has equated loans from the IMF and World Bank as being like borrowing from your mother. Ethiopia now owes an estimated $16 billion to Chinese lenders, roughly half of Ethiopia’s total debt. Abiy has called for debt forgiveness for the world’s poorest countries, from all international lenders.

Related: China’s new Silk Road traverses Kazakhstan. But some Kazakhs are skeptical of Chinese influence.

Zambia, too, has struggled to repay its debt. It missed a Eurobond payment, becoming the first African country to default during the COVID-19 pandemic, amid reports that Chinese lenders were pressing to take control of at least one copper mine if Zambia couldn’t repay its debt to China. And then there’s Sudan, where China’s arms-for-oil approach in the early 2000s contributed to mass killings in Darfur, in what the US government later called a genocide, with an estimated 400,000 people killed and thousands more displaced.

“In Sudan, in the early 2000s, this was the showcase country, that Chinese oil investment would bring peace, that Chinese infrastructure would develop the country,” says Luke Patey, author of “The New Kings of Crude: China, India and the Global Struggle for Oil in Sudan and South Sudan. … And what happened — not the Chinese fault, of course, but the Chinese didn’t solve it — there was a civil war, multiple civil wars. Sudan hasn’t developed. Now you have the Janjaweed that were militias in Darfur, displacing and killing civilian populations. They’re now in charge of the country to a large degree. So there wasn’t a happy ending to China’s investments in Sudan.”

Whether and when there will be a happier way forward in Ethiopia is now an open question. Here, too, China didn’t cause the conflict, and Chinese interests are squarely behind a peaceful and stable Horn of Africa, so China can move the commodities and other resources it needs from Africa.

But one thing China has learned on its new Silk Road is that even the most careful strategic planning only gets you so far. Much is beyond China’s control. And in response to China’s global ambitions, more global players have started their own outreach, with loans and investments, with more countries exercising more agency in deciding who to partner with and how.

“They have a lot more confidence than they did before,” says Parag Khanna, a global strategy adviser and author of books including “The Future is Asian.” “And the more the global system becomes a geopolitical marketplace of multiple competing powers, the more agency these smaller countries can actually have.”

So for all its imperfections, the Belt & Road Initiative may actually leave as its legacy a more multi-polar world, with states having more infrastructure, more investment, and more options than before, allowing them to better make their own decisions about what kind of future they want, and how to get there.

To borrow a phrase China’s leaders like to use: that certainly could be considered a win-win.

On China’s New Silk Road podcast is a production of the Global Reporting Centre. Full episodes and transcripts are available here.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?