New doc features the life of Iran’s leading human rights lawyer

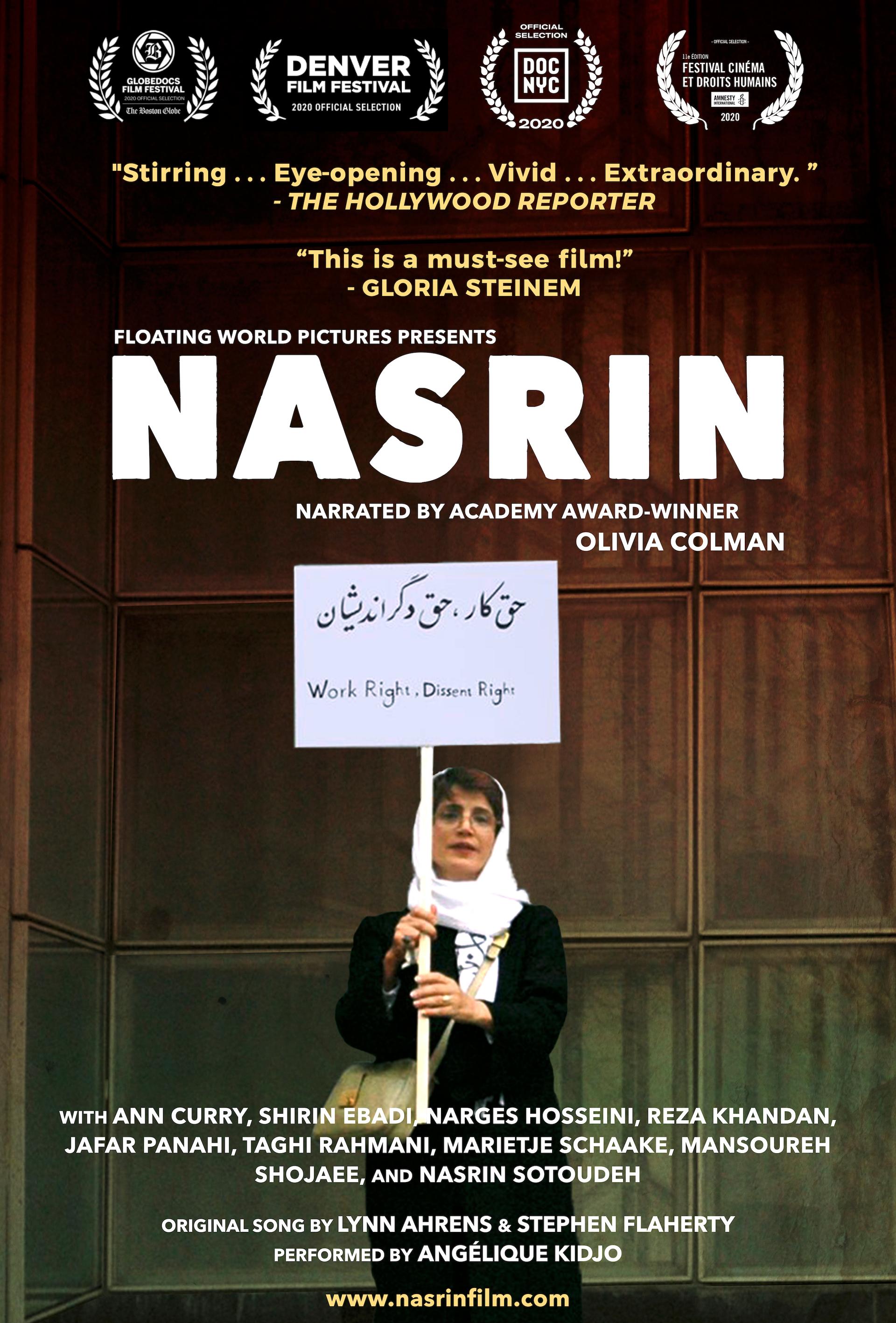

Iranian human rights lawyer and activist Nasrin Sotoudeh on the streets of Tehran before being imprisoned in a scene from the film “Nasrin,” directed by Jeff Kaufman and narrated by Oscar winner Olivia Colman.

For more than two decades, Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh has fought for the rights of women, children and minorities in her country.

Her work has won her international acclaim but also the wrath of the Iranian government. She has been arrested several times and is currently serving a 38-year sentence in prison. Her family has been detained and harassed as well.

This month, a new documentary called “Nasrin” takes viewers inside the life of Sotoudeh.

‘Child of the Revolution’

Hadi Ghaemi, founder and director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran, describes Sotoudeh as “a child of the Iranian Revolution.”

Born in 1963 in Langarud, Iran, Sotoudeh experienced the 1979 Revolution and its aftermath during her formative years, Ghaemi said.

Sotoudeh was a bank employee before she became a journalist and later, decided to study law and become a lawyer. As part of her work, she provided pro bono services to minorities and prisoners of conscience.

Related: As Iran arrests Instagram influencers, some seek safety abroad

“[Nasrin Sotoudeh] was breaking grounds with some of her colleagues in providing defense to those cases that no one else would take on like the LGBT community, religious minorities, people on death row.”

“She was breaking grounds with some of her colleagues in providing defense to those cases that no one else would take on like the LGBT community, religious minorities, people on death row,” Ghaemi said.

Iranian authorities arrested Sotoudeh several times in the past. She was jailed from August 2010 to September 2013 for her professional and human rights activities.

Her most recent arrest came in 2018 after she represented women who had taken off their headscarves to protest compulsory hijab laws, according to Human Rights Watch. In March 2019, the court sentenced her to 38 years in prison.

Related: Iranians share stories of sexual harassment on social media

Filmed secretly

“Nasrin” was directed and produced by Jeff Kaufman and Marcia Ross, who began work on the film in 2017, before Sotoudeh was arrested. The duo kept details about the film under wraps to avoid getting those involved in trouble with Iranian authorities.

“We kept it very quiet,” said Ross.

“Very often, when you make an independent documentary, you find public ways to raise money through a Kickstarter campaign, GoFundMe, and we did absolutely none of that with this film,” she said.

Kaufman and Ross hired anonymous contributors to follow Sotoudeh as she went about her daily life. They captured Sotoudeh at her office, home and in her car as she drove to court appointments.

The film also shows some rarely seen footage from inside a courtroom in Tehran, the capital. Sotoudeh is wearing a bright blue headscarf held in place by a knot under her chin. She is standing behind a podium, a stack of paper in one hand, her eyeglasses in the other. Sotoudeh is defending Shirin Ebadi, winner of the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize.

In the courtroom, Hossein Shariatmadari, a representative of Iran’s Supreme Leader, laments that Ebadi is “taking money from foreigners,” referring to the financial reward that comes with the Nobel Prize.

When Sotoudeh addresses the court in the video, she’s polite but firm. After a few minutes of back and forth, Sotoudeh tells the court that her rights and the rights of her client are being trampled on.

Then, she suddenly turns her back and walks out. Shariatmadari looks stunned.

“To step inside a revolutionary court and actually see Nasrin stare down and argue down a prosecutor and a judge is pretty intense.”

“To step inside a revolutionary court and actually see Nasrin stare down and argue down a prosecutor and a judge is pretty intense,” said Jeff Kaufman in an interview with The World.

“Nasrin Sotoudeh, I think, represents all the standards we need for a role model around the world today. Not just for Iran. She’s a remarkable woman,” he said.

In “Nasrin,” the audience gets to know Sotoudeh as the defiant lawyer who stands up for the rights of women, children and religious minorities, but also as an art lover, a wife and a mother.

In one scene, Sotoudeh picks up her son from school and they hold hands as they walk home.

“In every society, it’s the youth that are most vocal about injustice,” she says in the narration. “I hope one day, there’s peace in my country. Then, we can make films and write poems about it.”

‘No regrets’

Incidentally, when The World reached Sotoudeh’s husband, Reza Khandan, by phone in Iran, he too was about to pick up their son from school.

Later, Khandan explained that his wife’s health has been deteriorating in prison. Sotoudeh went on a hunger strike last month as a way to protest the conditions in prison and the treatment of her family by the authorities.

Khandan said his wife is suffering from heart problems, too, and she is in need of medical attention.

On Wednesday, Khandan tweeted that instead of being taken to a hospital, Sotoudeh has been transferred from the notorious Evin prison to a prison outside Tehran.

“This government is fearful of people like my wife. … They know she is not giving up.”

“This government is fearful of people like my wife,” Khandan told The World. “They know she is not giving up.”

Khandan said his focus now is to try and make life as normal as possible for the couple’s two children — to give them the support they need in the absence of their mother.

Filmmakers Kaufman and Ross said they learned a lot about Iran, but the film also made them reflect on what could be at stake here in the US:

“An effort over and over again to push back on civil rights and human rights, voting rights, women’s rights, minority rights, pushing religious intolerance, all that’s been happening in this country as we’ve been making this film about human rights in Iran,” Kaufman said.

Related: In Iran, all eyes are on US election’s impact on sanctions, security

He hopes that the film serves as a reminder to Americans not to let their liberties slip away.

And to get out and vote.